Fashion Still Thriving Off Low‑Paid Women Garment Makers

Despite pledges to improve pay and working conditions, a new report finds the fashion brands are still exploitative.

Fashion, an industry that disproportionately exists for female consumers, is still making its clothing by exploiting its garment makers — the vast majority of whom are women. This is not news. What is news is that, six years after an international tragedy spotlit this problem, next to nothing has been done to resolve it, concludes a report by researchers at the University of Sheffield, in the U.K.

In 2013, consumers and fashion brands alike were awakened to exploitative manufacturing practices when more than 1,100 people died in the collapse of Rana Plaza, an eight-story building outside Dhaka, Bangladesh. It had housed several garment factories from which clothing was made for international brands including Benetton, Mango and more. The day before the collapse, workers had noticed cracks in the building, but were ordered to come to work anyway.

In the wake of the disaster, under pressure from consumers, fashion brands committed to improving conditions and pay for workers. However,“there is little evidence that corporate commitments to living wages are translating into meaningful change on the ground,” Genevieve LeBaron, director of the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute, which authored the report, told The Guardian. “As such, consumers are purchasing products they may believe are made by workers earning a living wage, when in reality, low wages continue to be the status quo across the global garment industry.”

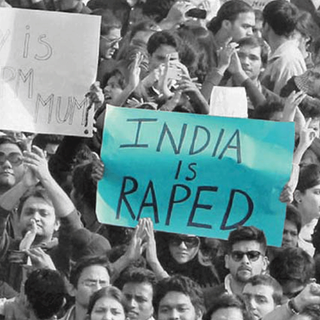

Women disproportionately bear the brunt of this exploitation. As many as 80% of global garment workers are women, according to the International Labor Organization. In addition to not earning a living wage, these women often face a sizeable pay gap compared to their male peers; in India, the gender pay gap in the garment manufacturing industry is 53.3% — much wider than the country’s formal workforce gender pay gap at 34%.

Related on The Swaddle:

Manufacturing New Clothes Will Always Harm the Environment

Hints that pledges to increase living wages for garment workers were hollow have been building for some time. Most fashion brands don’t actually own their factories, but rather outsource their production, which translates to little control over how their pledges play out on the ground. Take H&M: After the Rana Plaza tragedy spotlit the exploitation of garment workers, the fast-fashion behemoth promised to pay a “fair living wage” to its 850,000+ factory workers across 750 factories by 2018. “By 2017, however, H&M’s language regarding its living-wage strategy took a slight turn. The 2018 goal was to have “improved wage management systems in place” at suppliers representing 50 percent of its product volume,” reported Jasmin Malik Chua for Vox last year.

And in April of this year, Bangladeshi garment workers protesting an increase in minimum wage (to US$0.45 an hour) — which would still keep them the lowest-paid garment workers in the world — faced mass firings and false arrests.

As the University of Sheffield report notes, “a minimum wage is a legal floor under which wages cannot fall, [while] a living wage is defined by various necessities such as food, housing, medical care, clothing, and transportation that people need to live. “

The new report names no names; it examines the commitments of 20 global garment companies. But it doesn’t have to — underpaid garment workers are starting to speak out. Last year, #payupuniqlo made the media rounds as workers from a bankrupt factory in Indonesia demanded US$5.5 million in unpaid wages from the Japanese clothing brand. They say the factory was made insolvent when Uniqlo pulled its business without warning and without paying its bills. Fast Retailing, which owns the brand, insists it has acted lawfully.

But lawfulness isn’t the issue anymore, and hasn’t been for a long time. With “ethical fashion” the new buzzword, fashion companies need to be held to a higher standard — one that doesn’t rely on taking their word at face value. And there’s only one group who can do it: consumers. The devil doesn’t have to wear Prada.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

‘Tuca and Bertie’ Showcases a Raw, Messy View Into the Female Brain