Female Immune System Could Hold Key to Fighting Cancer, Autoimmune Disorders

Scientists are calling for more research into how women’s reproductive cycles make their immune systems unique.

A group of scientists is calling for more research into the female immune system, suggesting in a paper published in the journal Trends in Genetics that its differences from the male immune system could hold key insights to autoimmune disease treatments, as well as cancer immunotherapies.

Currently, the scientific community does not know why women are much likelier than men to have autoimmune disorders, nor why women tend to respond better to immunotherapies to treat cancer. Autoimmune disorders occur when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissue. And immunotherapy is a promising line of cancer treatment that artificially stimulates the natural, disease-fighting function of the immune system and directs it toward inhibiting the growth of cancer cells. Insight into why women are affected differently by both could pave the way to better immune system-targeted treatments for patients of all sexes.

“Until now, the differences between women and men in regards to human diseases have not been explained by existing theories,” Melissa Wilson, PhD, an assistant professor with Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences and a senior author of the paper, said in a statement. Wilson and her co-authors are hypothesizing that “women’s immune systems evolved to facilitate their survival during the presence of an immunologically invasive placenta and pregnancy, and compensate so they could also survive the assault of parasites and pathogens,” Wilson explained. In other words, their immune system had to both protect them, and also allow for a literally foreign body to take up residence inside them. “But now, in modern, industrialized societies, women are not pregnant all the time, so they don’t have a placenta pushing back against the immune system. The changes in their reproductive ecology exacerbate the increased risk of autoimmune disease because immune surveillance is heightened. At the same time, we see a reduction in some diseases, like cancer.”

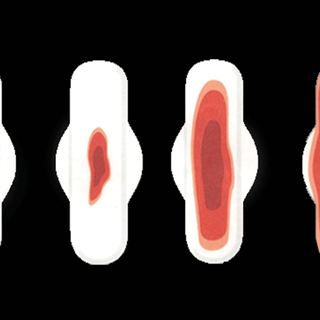

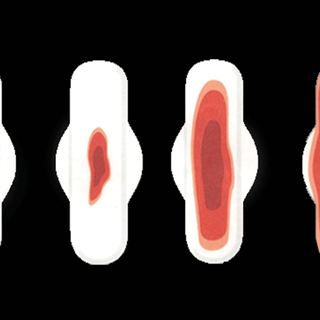

It’s not the first time scientists have sought to link women’s immune systems and reproductive cycles. Last year, The Swaddle reported on a study that found an undiagnosed sexually transmitted disease can worsen premenstrual syndrome symptoms. “The whole function of the menstrual cycle is to produce cyclical patterns of immunity, so actually we would be better to think of female health as cyclical,” the then-study’s lead author Alexandra Alvergne, PhD, of the University of Oxford, U.K., said at the time. “To truly understand women’s health we need to better understand reproductive health, as the two go hand in hand.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Mice Study Suggests Previously Unknown Trigger of Autoimmune Disorders

In the new paper, scientists suggest that our modern, sanitized environments may stress women’s immune systems in ways different from male systems, and different from our forebears’ immunity. They also argue that modern diets may stress women’s hormone production in a way that influences their immune system. “Maintaining such high levels of hormones may increase the chance of triggering autoimmune diseases,” said Angela Garcia, one of the paper’s authors and a postdoctoral research fellow with the ASU Center for Evolution and Medicine.

Ultimately, the researchers’ point is: we don’t know. And we won’t, without more research that focuses specifically on women. Until recent years, most scientific studies were conducted on male subjects; women’s hormonal fluctuation across their menstrual cycle was seen as making results unreliable and conclusions more difficult to reach. Slowly, this is changing; research funders are starting to require studies to include female subjects. And papers like this one will hopefully help the situation change faster.

“Our goal is to actually make treatments better for everyone. We are realizing that cancer is different in men and women,” Heini Natri, one the paper’s authors and a postdoctoral scholar with the ASU Center for Evolution and Medicine, said in a statement. “In the study of most cancers and other diseases, and so far in the development of cancer treatments, that has not really been taken into account.”

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Father‑Child Bond Is Strongest When Fathers Prioritize Parenting Work Over Playtime