From Hearing Colors to Seeing Ultraviolet, Is Enhancement the Future of Human Senses?

Cyborgs among us are already employing tech to “unlock” new senses and alter their reality.

In The Future Of, we unpack technology’s growing influence on our lives to answer the pressing question — What lies ahead?

Neil Harbisson has been hailed as the “world’s first cyborg artist.” “I’ve been a cyborg for 10 years now,” he told The Guardian in 2014. “I don’t feel like I’m using technology, or wearing technology. I feel like I am technology.”

Born with achromatopsia, a rare form of color blindness that allows one to see only in shades of gray, Harbisson designed a metal antenna – which he later convinced a surgeon to drill into his skull – to help him perceive color through sound. Recently, he said this device, which he dubbed the “eyeborg,” was devised more as an artistic challenge than as a solution to fix color perception. The device vibrates based on the color frequency it picks up, reported EuroNext. These vibrations are then translated into sound, traveling to the inner ear through bone conduction. It works inversely too; he can even sense color when he listens to sounds. As he told The Guardian, a telephone ring is green, while Amy Winehouse is red and pink.

Our senses play a crucial role in shaping the way we construct our reality. The loss of a single sense can impede that process. Yet, millions live with one or more forms of sensory impairment. For instance, the World Health Organization estimates that around 2.2 billion people across the globe live with some form of visual impairment while predicting that by 2050, 1 in every 10 people will have disabling hearing loss. Harbisson’s self-fashioned “eyeborg” is a prime example of how technology can not only help restore lost sensation but, crucially, change perception – in this case, by substituting one sensory pathway with another. Over the years, research has unearthed a range of such possibilities with devices that allow one to not only see color through sound, but even hear through touch or see through taste.

But the trajectory of tech has now moved beyond serving as an aid to enhancing sensory perception. As researchers discover more about human bodies and minds, work in this field is also looking to augment existing senses (think: night vision, super hearing or a sense of smell that allows you to filter out certain odors) and unlock entirely new senses we never knew we had. Harbisson’s implanted device, for instance, allows him to perceive ultraviolet and infrared colors that lie outside the normal range of human perception. Herein lies technology’s potential for human augmentation – a prominent cultural fantasy that imagines a world where humans meld with machinery and emerge as cyborgs.

Substituting senses

Earlier this year, the Washington Post reported that researchers at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine are developing a neuroprosthetic that could help many suffering from a loss of smell. This device, which comes in the form of a “bionic nose,” becomes all the more significant when factoring in the estimated 15 million people who suffer from long-term issues with smell post Covid.

The “bionic nose” is currently a prototype sensor that can be attached to wearables. The sensor detects odors, sending signals to an electrode array implanted in the brain, which then stimulates a part of the brain in a specific pattern, generating the perception of smell.

Related on The Swaddle:

Humans May Be Losing Their Sense of Smell Over Time

With time, these aids are becoming more advanced. Bionic limbs can now sense temperature variations, and restore not only the sensation of touch but also unconscious reflexes. Combining these aids with artificial intelligence and virtual reality has led to the creation of hearing aids that can detect heart rates and monitor physical activity, and even contact lenses that measure the body’s vitals.

But some of the most intriguing advancements have emerged through a technique known as “sensory substitution” – which scientist David Eagleman’s website defines as a non-invasive technique that restores a lost sense by using a different sensory pathway – for example, restoring sight using the sense of taste. This technique relies on the brain’s neuroplasticity that says the adult brain is capable of adapting by rewiring its neurons. According to Wired, one of the earliest works of sensory substitution technology emerged in 1969, when Paul Bach-y-Rita created the first prototype of what would later become the BrainPort V100 – a device that received FDA approval in 2015 and allows blind people to see using their tongue.

The BrainPort detects a visual stimulus and converts it into electrical pulses which are then sent to stimulate the tongue through attached electrodes. It requires a fair bit of practice to master, reported the New Yorker in 2017, and is also expensive. There are a number of such sensory substitution devices that have emerged, including BrainPort’s alternative vOICe that substitutes sound for sight. Their results however, the New Yorker noted, are limited. “The BrainPort’s images are, after all, gray-scale and low-resolution, and its auditory competitor, the vOICe, operates with a built-in time delay, so it can’t even help you cross the street,” wrote Nicola Twilley.

Eagleman, too, employed this technique to create the Versatile Extra-Sensory Transducer, or simply, VEST. The idea was that hearing-impaired people wearing this vest containing vibration motors would be able to hear through touch. A phone app would capture sounds and send them to the motors in the vest, which would then translate this into patterns of vibrations on the skin.

“The pattern of vibrations that you’re feeling [while wearing the VEST] represent the frequencies that are present in the sound… What that means is what you’re feeling is not code for a letter or a word—it’s not like morse code—but you’re actually feeling a representation of the sound,” Eagleman told The Atlantic in 2015.

When the team tested the prototype, the subject was able to understand the words spoken to him in five days, which Eagleman attributed to his brain beginning to “unlock” the meaning of that data or information. This is sort of like adding an entirely new sense to enhance our perception.

And that’s exactly what Eagleman, and many other scientists are hoping to do.

Augmenting senses

The human plane of perception is limited. What we hear, see or smell is a filtered reality, where only a part of the information around us makes it to our brains. There’s still a lot of information in the world that our brains have not been processing because our senses were not able to capture that data, at least till now.

Eagleman’s VEST started as a sensory substitution device, but soon crossed the threshold into augmentation. The input, as Eagleman told Wired in 2016, doesn’t have to be sound, but could include non-sensory information as well. From Twitter posts to stock market data, the VEST makes it possible to perceive a range of information through touch. “People can feed in whatever data stream they want to,” Eagleman said.

Meanwhile, Kevin Warwick – cybernetics researcher and deputy vice-chancellor at Coventry University – has been experimenting on himself since the late 1990s. Warwick once had microchips embedded underneath his skin that allowed him to open automated doors and control lights. BBC Science Focus reported that later, he went ahead with the risky procedure of having neural implants embedded that allowed him to control a robotic arm halfway across the world, while also communicating with his wife’s nervous system through electrodes in her arm.

Then there is Cyborg Nest’s NorthSense – an implant that vibrates every time someone is facing North. This device works on the basis of magnetoreception – an ability that many animals have to align with the magnetic field of the earth. “If you use technology to have a deeper relationship with living things—to understand them better—then your point of view changes. I think of us as explorers of perception. We know that our planet is like this because we perceive it like this as human, but there are actually so many layers we cannot see or perceive,” said Moon Ribas, co-founder of Cyborg Nest who had sensors implanted in her body for seven years that allowed her to feel the Earth’s seismic activity.

Transhumanism

As many have argued, cyborgs already exist. From prosthetics to implanted pacemakers, there are countless ways in which the human body is merging with technology and blurring how we understand the natural versus artificial. The difference is that in the future, it would not be so much out of necessity than curiosity – as a way to enhance our senses and radically transform how we perceive the world and, therefore, our lived experiences.

Harbisson, for example, is the first person to be legally recognized as a cyborg. Along with Ribas, he founded the Transpecies Society that “gives voice to non-human identities,” and helps design cybernetic organs to add new senses. “I don’t think of my antenna as a device – it’s a body part,” he said. Harbisson envisions it as a way to connect deeply with the natural world around him as well, in complete contrast to how the technology versus nature debate usually goes. As he told Document Journal, it could even aid climate action. “Having night vision is the most obvious example, because we won’t have to use energy to create artificial lighting… Or, we can start to regulate our temperature, so we don’t need air conditioning.”

However, enhancing human perception also raises challenging questions for a world that seems ill-prepared for a cyborgian future at present.

Related on The Swaddle:

What Is Transhumanism and Why Do People Associate It With Eugenics?

With technology come the usual concerns around accessibility, affordability, and privacy. Recently, Harbisson sold “access” to his head in the form of a nonfungible token (NFT) as an artistic endeavor. This would allow the buyer to not only perceive the world as Harbisson sees it, but also send colors to his head, effectively changing Harbisson’s perception of reality. “The tricky part in this case, however, is the possibility of being hacked and stolen for the financial potential of the NFT marketplace,” Vitor M. Lima wrote in the chapter “Transhumanism and the phenomenology of cyborg senses” in The Routledge Handbook of Digital Consumption.

The risks of misuse are high — technology can be hacked to gain access to one’s senses and be used for social manipulation, all the while infringing upon one’s personal autonomy. Augmented sensory technology can be programmed to contain erroneous information and since big companies will probably be the ones providing these augmentation experiences, “the creator of the technology has the power to control what the user sees or hears. Even though this may seem like an irrelevant concern, it offers the potential for manipulating the user through lifelike augmented and pervasive sensory experiences,” wrote the authors of a 2019 paper on human augmentation.

The idea of using technological developments – including genetic engineering, nanotechnology and AI – to enhance our bodies beyond our current limitations and create a species that is part-human, part-machine and vastly more intelligent, productive, powerful and even immortal, is a fundamental part of the transhumanist ideology, which finds its most ardent supporters in white, male tech billionaires. Critics have also noted that the transhumanism perspective is rooted in 20th century eugenics – a history that could play out well into the future by creating inequalities that are not limited to economics but based on biology.

Human augmentation technology has its basis in research on creating therapeutic aids for those living with a sensory impairment or disability to foster greater inclusion. But the vision is to make this technology — that can design senses, add artificial limbs or genetically engineer one’s characteristics –available to those who can afford it. Oliver Armitage, founder of Cambridge Bio-Augmentation Systems (CBAS), told Dazed magazine, “We do this because there’s real medical need now for those people, but I’m also excited by the fact that in the process, you also create technology which could allow people to add to themselves if they wanted to. If they need a limb for climbing, they can have a climbing limb. There’s no limits on what a person can choose to have put on the end of our interface.”

There will need to be a significant overhaul of the legal landscape, including coming up with international guidelines, to address the ethical challenges augmentation raises. And while the cyborgs are a small community at present, there are many predictions that consider technology to be the next frontier of human evolution, imagining a future where human augmentation becomes inevitable. “It’s a myth that human augmentation is anything new,” Amal Graafstra, a microchip implant pioneer, told The BBC in 2014. “From rudimentary objects like rocks and sticks, through forged steel and circuit boards, and onward to gene therapies – the common thread is transhumanism; to constantly and fundamentally transform the human condition.”

Some believe it’s possible that a society of enhanced humans could be a positive step forward. As authors of the 2019 paper noted, any technology can be used for good or bad. It is only by addressing the ethical quandaries that may arise with its implementation that the world can harness its potential to create an equitable future for everyone.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

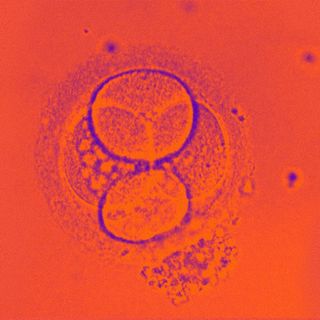

The First Synthetic Human Embryos Are Here — Are They Ethical?