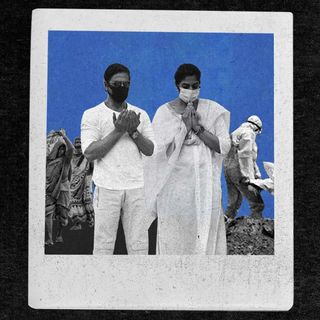

‘Gehraiyaan’ Shows How Childhood Traumas Can Shape People’s Narratives With Sensitivity

Shakun Batra’s “slow-burner,” in some ways, empowers survivors of childhood trauma to choose their narratives, rather than being defined by their past.

Warning: The article mentions suicide and self-harm. It also contains spoilers.

Gehraiyaan‘s trailer carried a strong hint of being a millennial iteration of 2006’s Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna — but with an upper-class Instagram aesthetic. The movie stays loyal to some of those expectations — it explores the visual language of human vulnerability and complex relationships. But the mood saga-cum-drama-cum-thriller goes a lot deeper than that — true to its title, which translates to “depths.”

The movie may have its share of flaws, but it does attempt to explore love and loss — of partners, family, and oneself — through a sensitive, humane lens. Director Shakun Batra weaves intergenerational trauma, along with the tussle between free will and helplessness in the narrative. What makes Gehraiyaan‘s narrative stand out the most is that it prompts the audience to judge both Alisha and Zain — played by Deepika Padukone and Siddhant Chaturvedi — within the first 20 minutes. Then, it begins to challenge its audience’s perceptions through complex backstories for both of these characters. Alisha, played by Deepika Padukone, is presented as someone who feels she is the “unluckiest person in the world.” She is often shown wandering into memories from her childhood — ones that, from her perspective, show her father destroying their family by uprooting his unwilling wife-daughter duo from their life in Mumbai, and eventually pushing Alisha’s mother into a state of “feeling stuck” that eventually leads her to die by suicide.

But Batra unsettles his audiences again after they’ve made up their mind to empathize with Alisha. At its outset, the movie hinted at the character of Alisha’s mother being a self-sacrificing woman catering to her husband’s ego-driven life decisions, who felt so helpless in life that she ended it. However, as the movie draws to a climax, it flips the narrative to show Shah as the victim of her mother’s actions. At this juncture, we learn that Alisha’s father, Vinod, played by Naseeruddin Shah, is also a “victim” in his own narrative, who is still struggling to pick up the pieces after his wife’s actions shattered his life.

By this point though, the movie has proved how quickly we, as a part of society, jump to judge people.

Its “third act” — if I may — forced me to wonder: what if Alisha’s mother, too, had a traumatic backstory the movie couldn’t get into? Can I really judge her without knowing anything about the circumstances of her upbringing, her marriage — than the one seemingly bad decision she made to have an affair with her husband’s brother? Is it ever fair to form an unwavering opinion of someone until we have heard why they did what they did from their own mouths? Is the unfairness implicit in doing so, the reason why lived experiences matter, and why legal systems, too, allow the accused to present their version of events before condemning them?

There is no one “victim” or one “oppressed” in any story. And therein lies the social impact Batra made with Gehraiyaan.

Related on The Swaddle:

‘Atrangi Re’ Attempts to Simplify Mental Health, but Ends Up Romanticizing It

Unlike what its trailer might make one assume, the movie does not condone cheating. What it does, instead, is help its audiences understand why people may decide to stray despite promising to be in monogamous relationships. Their decision may be a “bad” one that wrecks many lives; but, at least, we can see they’re not inherently bad people and all their actions were but a result of how they made poor, unethical choices to deal with their circumstances. Does that apply to every individual who “cheats”? Perhaps, not. Does that absolve them, and mean they shouldn’t have to suffer the consequences of their actions? Absolutely not. But should that define them and make them undeserving of empathy? No, again.

“Her life was bigger than that one mistake… there was so much more to her,” Shah’s character says of his wife. For me, that line sums up the point Batra tried to drive home with Gehraiyaan.

Notably, Shah’s cumulative screentime in Gehraiyaan could not have been over 20 minutes. Yet, through the way his character was written, — and, of course, through the Shah’s almost Mystique-like ability to transform into just about any mortal as if he were a shapeshifter — makes Vinod one of the strongest, meatiest characters in Gehraiyaan. At least, more than 10+ hours since I watched the movie, his character has lingered on my mind way more than Zain whose death I found oddly comforting.

I’m not sure yet whether it was Chaturvedi’s personality that made his screen presence difficult to tolerate, or if it was his brilliant rendition of a very-very-dark gray character that made me dislike him. However, through Zain, too, Batra asks the same difficult question of his audience: “Can you judge people after knowing their story and struggles?” as one review put it. I’m inclined to answer in the affirmative for Zain, despite knowing his backstory. But for Alisha, I’m miles away from even beginning to judge her, especially given how her character personifies the underlying narrative of the movie — about how past traumas, always functioning as invisible strings, regulate how we love, grieve, and even just exist.

Both Alisha and Zain survived traumatic childhoods. Yet, it shaped their narratives very differently because of the different choices they made. Alisha’s mother died by suicide, which made her constantly fear ending up like her mother. Nonetheless, she took up the mantle of caring for her father — whose grief led him to slip into substance abuse — despite blaming him for her mother’s death. Perhaps, she felt her father didn’t care about them, her despise towards him drove her to aspire to be the opposite of him. Zain, on the other hand, wanting to “save” his mother from domestic abuse, filed a police complaint against his father. He didn’t get arrested, but instead, injured Zain so grievously that a decade later, his forehead still bore a scar — symbolic of how it scarred him emotionally too. His reaction was making a choice to leave his family behind for the sake of self-preservation.

The choices they made defined their present narratives. Zain was willing to cheat people — emotionally as well as financially — to safeguard his desires, his ambitions. His sense of self-preservation, over time, evolved into selfishness so extreme that he was willing to murder Alisha, who was pregnant with their child, just so his fianceé would bail him out from the consequences of his deliberate, shady business transactions. Alisha, on the other hand, cheats too, yes. But her conscience also leads her to soon break up with both her fiancé and Zain, who continues to flirt with her while also continuing to be happily engaged to Alisha’s cousin — just because her pockets were, to him, irresistibly gehra (deep).

Moreover, both Zain’s and Alisha’s prospective spouses are portrayed as rich, spoilt kids — almost insufferably so — who may never be able to grasp the traumatic pasts of their partners fully. This, to some extent, helps the audience see why the lack of understanding from their significant others would drive them into the arms of someone who can empathize with them. However, fed up of her fiancé, Karan, played by Dhairya Karwa — and, perhaps, plagued by the guilt of her infidelity — Alisha breaks up with him after being cornered into accepting his very-public marriage proposal at her surprise birthday party. Zain, on the other hand, gaslights his fianceé, Tia, played by Ananya Pandey, when she confronts him with her suspicions of him cheating on her and using her for money.

Related on The Swaddle:

Perhaps, the movie’s relatively sensitive depiction of Alisha’s mental health issues — manifested in the form of debilitating anxiety, insecurities, emotional dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors as a result of both childhood and inter-generational trauma — made the process of empathizing with her character easier. Moreover, as a person who has self-harmed in the past and been shamed for it, the composure with which Shah’s character is shown to deal with the discovery of his daughter self-harming, was not something I was expecting from a mainstream Bollywood movie.

Gehralaiyaan tries to show how one’s childhood traumas can define their narrative, but also how, through their own choices, they have the power to redefine it — to some extent, at least, if not entirely. When Shah’s character says, “You don’t need to run away from the past. Accept what happened [and what you did]. But always choose to move on,” I found myself flinching for a couple of seconds at yet another pop culture moment, suggesting it’s easy to move on. But through its narrative, the movie never actually suggests it’s easy to move on at all — in fact, it’s plot is but a constant reminder of quite the opposite.

By encouraging acceptance of who we are, Gehraiyaan attempted to empower survivors of childhood trauma to choose their narratives — perhaps, through therapy and counseling, or even joining support groups — rather than being defined by their past. Instead of blaming people’s reactions to the trauma they endured, it suggests that healing — so they can salvage their own mental health and regain some control of their lives — might yet be a possibility.

The film’s handling of intimacy, too, sets a benchmark in some ways. On the one hand, it dips it’s toes into myriad forms of emotional intimacy –suggesting that intimacy isn’t limited to “steamy” scenes. Besides, the decision to credit the movie’s intimacy director, Dar Gai, on its poster, also highlights the importance of the role that has become all the more necessary in the wake of #MeToo. “You need to make sure you’re having the right conversations. You need to make sure you’re establishing boundaries, not violating people’s privacy or personal space,” Batra had told The Swaddle’s Rajvi Desai early last year, explaining why it’s important to have an intimacy director.

However, the movie’s primary focus, to me, seemed to be it’s exploration of trauma and complex emotional baggage. Yet, despite its two-and-a-half-hour runtime, the movie doesn’t leave it’s audiences with all the answers. In doing so, the movie seems to box itself into an existential cage. But the cage is one that makes its audiences uncomfortably introspect why they view the world the way they do, and why they are the way they are.

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

Rue Is Euphoria’s Beating Heart