How a Culture of Guilt Around Spending Fractures Young Indians’ Relationship With Money

“I was interested in buying a keyboard recently… but [the decision] almost gave me a panic attack.”

At 23, Shahrukh Mohammed realized he didn’t know how to spend his money. He arrived at an online shopping festival, his mind already made – all he wanted was a keyboard. The keyboard was an investment, Shahrukh told himself, as an act of justification. Still, he scrolled up and down the page to absorb the details, the reviews, the offerings of this purchase – looking for anything that might help him make his case for why he needed a new keyboard.

“I was relentlessly calling my best friend and my sister to seek affirmations that I was doing the ‘right’ thing,” he recalls. Purchasing a keyboard meant he was “pampering” himself. Was he spoiled and indulgent? What would his parents make of his decision? “It almost gave me a panic attack.”

This attitude around spending money – that is intrinsically linked to guilt – is one many young Indians resonate with. Along with the question of where to spend money and whether the expenditure is responsible and within one’s means also comes the matter of how to rationalize the act of spending to oneself.

“I have that guilt so much that after purchasing something I immediately regret it,” says Shreya Narula, 28.

Namrata Khetan, a counseling psychologist, lists three factors that largely shape how we perceive money and finances: psychological (personal beliefs, motivation, attitudes, and individual experiences), social (family status, class, and occupation), and cultural (the ideas and values we glean from the larger community around us). The role of family upbringing cuts across these three dimensions, shaping much of our beliefs, experiences, and values that we carry as individuals. “The conversations our parents have around money and expenses get passed onto us and shapes our relationship with money.”

And in Indian families, there is perhaps no bigger taboo than discussing the intimate details of one’s monetary status. This air of secrecy and lack of transparency means that children’s relationship with money becomes fractured even before it can form. “I never learned to spend money as a kid,” says Abhilash Mallick, 28. “Whenever I’d ask for something, something as small as a packet of biscuits, my parents would say they’d get it for me.”

And when we do speak of money, saving and holding on to what you have is romanticized. It is seeped into the very language used to talk about it. Whenever Abhilash got money at family gatherings, “I was asked to give it to my parents. My mom would put that money into fixed deposits and remind me often about ‘my’ savings.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Blockchain Ideology Is Rooted in Exclusion. A Feminist Lens Shows Why

Much of this attitude can be traced to financial insecurity – maybe in the form of debt, overspending, or structural disadvantages – during childhood. Shahrukh’s parents come from humble backgrounds; when they moved him to a cosmopolitan city when he was young, he had to navigate a completely different socio-economic landscape. “For us, going shopping at a mall began as a guerilla experience – going and getting only what we need and only observing all the luxuries,” he remembers. “Me and my family felt quite distant from all of it.”

When all household spending is plotted on a vector of constraint, of prioritizing needs over wants, the individual psyche towards money also shifts. One study found that witnessing financial scarcity in early childhood can have PTSD-like symptoms in individuals. This leads people to grow up to do one of two things: either ignore all finance-related concerns (called money avoidance, which is linked to an upbringing where parents overspend) or be compulsively concerned and insecure about money. “I still operate from a mindset of lack, living from paycheck to paycheck, understanding the price of a commodity/service not just in units of a currency but also units of how many – insert basic item you regularly buy for survival – can be bought in that price range,” says Khushi*.

*

The Indian Family is by design interdependent. It is a quintessential collectivistic culture that prizes the institution over the individual. This means any earnings are viewed as belonging to the family and not the individual; individual agency and boundaries are negated for income to be seen as a collective resource. Even when it’s one’s hard-earned money, one is forced to feel that it isn’t really their money.

All this allows for a cycle of guilt and emotional manipulation to play out within families, further complicating how an individual, separate identity is framed. If money is never theirs to own, or ascribe meaning to, young people participate in a cultural exercise of distancing themselves from finance. And there is no real loss incurred in forfeiting ownership of something we never learn to see as our own. We sire a worldview where the emotional currency of familial support takes precedence over financial currency.

Moreover, money in Indian households is entrenched within power and who is allowed to claim it. The enterprise of the Indian family allocates the domain of finance to the “head” of the house; the others are merely accessories to this operation. Arguably, the head of the family is predominantly a male figure by virtue of gender roles, which casts the relationship young women have with money in murkier tones.

Growing up with this cultural spectacle makes it almost “unnatural” for women to comment on money matters. Never watching their mothers make the financial decisions leaves young women grossly ill-prepared for when they have to make these decisions in their life. This is evident through research that illustrates why women are more risk and loss averse than men when it comes to financial decision-making.

“One of the biggest reasons why my upbringing didn’t prepare me to save systemically is that I was never a part of these conversations in my family,” says Anushree Gupta. “Sure, I always knew it’s important to save, coming from a middle-class family. But, when I became an earning adult, I struggled with the how of it.”

Researchers have noted that any social conditioning at such a scale can be highly disorienting, more so for people who find themselves newly immersed in a world that demands financial literacy from them. D.V., 24, recently bought a laptop with her own salary and “felt extremely anxious regarding what to choose and finalizing the product without consulting with my family.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Many Indian Families Express Care Through ‘Bullying,’ Creating Patterns of Abuse

Parul* says “even after getting a job and an independent bank account, my father was always involved in my accounts and expenses.” This dependence and reliance further cage single women in a setting where spending for oneself, or for individual needs, is often restricted.

This toxic interdependence then also births a cycle of obligation. “If young adults or children are dependent on their family, parents or caregiver for money and expenses it makes them feel obligated directly or indirectly,” Namrata points out. Not only does this prevent them from being able to spend but also “impacts autonomy and boundaries, causing feelings of guilt, lack of control, stress.”

Rahul* wanted to join the armed forces, which would require months and years of studying for entrances, delaying his earning prospects and thus his ability to take care of his family. “During my boards, I felt like I was wasting my time, and should start doing something that will earn me quick money. I began to see education as a ‘waste’ of money – and I still feel guilty sometimes.”

“We have never been encouraged to prioritize ourselves or needs over family,” Namrata says. “Even if we did, the guilt and shame is monumental just in the way we are conditioned.”

Moreover, it’s the family that shapes the meaning of “value,” and thus also constructs the fine line between “needs” and “wants.” The family decides how to save, where to invest, what expenses to be at peace with. All expenditure is excessive, unless it offers a tangible form of utility that is sharable and sustainable. “I’m always guilty about spending on one-time pleasure activities, because my parents would constantly remind me that I’m just finding an excuse to spend money,” says Parul.

Beyond guilt, this dynamic also shapes the way people look at investing money. When one’s upbringing pedestalizes “holding on to what you have,” people learn to see investments as something to be anxious about and not approach with prudence and knowledge. That is, when one never learns to spend money, they never learn to compound it either.

“I feel like my upbringing hasn’t prepared me at all for saving money smartly,” says Anushree. “It took me a long time to get to a point when I could say I was responsibly saving and investing money.”

Investing when detached from its intimidating associations with stocks, funds, property also means it is a form of growth – of endowing someone with things both material and immaterial. This means investing money not only in its tangible form of a currency, but on the self too.

“I have deferred therapy for the longest time because I felt that was an unnecessary expenditure,” Shreya says.

Like Shreya, many young adults find spending on any kind of self-care equally alien. Rahul* wants to take up yoga, or even gently dip his feet in other “hobbies,” but “I see them as a waste of time.” Instead, he chooses “to study hard to get good results, which make [him] feel worthy and others happy while spending on me.”

The dynamic muddies up our relationship with not only money, but ourselves – as living, breathing individuals with agency to decide what matters to us.

*Names concealed to protect anonymity.

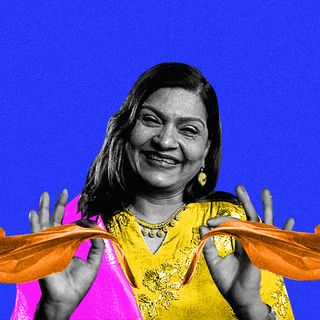

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

How Representation in Horror Films Creates Space for Our Most Urgent Fears