How a Photo of Khloé Kardashian Reignited Debate on Motherhood, Surrogacy, and Global Inequality

At the heart of the debate is how wealth, labor, and bodies intersect globally over the question of “authentic” motherhood.

Not all bodies can get pregnant. But who gets to have access to bodies that can?

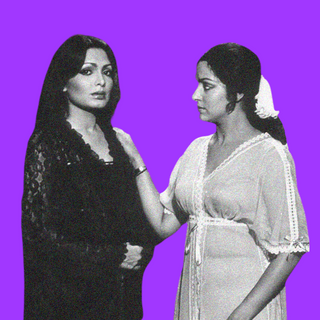

When reality star Khloé Kardashian posted a photo of herself with her newborn child in a hospital bed, the internet was rife with this very question — given, especially, that the baby was born via a surrogate mother. Suddenly, a seemingly innocuous photo turned political — making motherhood itself a burning topic of debate. In the photo, Kardashian performs motherhood without performing the labor (literally). There are loaded connotations to a baby’s first picture with its mother: it has to signify joy, reward, and have all the bearings of being the light at the end of a nine-month long tunnel. This particular photo, then, speaks volumes about how motherhood is deeply intertwined with bodily labor. Does the photo-op then make Khloé Kardashian an inauthentic mother?

There’s two kinds of surrogacy: altruistic and commercial. The former entails no payment, and involves only those actively volunteer to carrying a fetus for someone else out of goodwill. The latter, however, is the subject of heated debate among feminists and ethicists.

Khloé Kardashian isn’t the first celebrity to become a parent via surrogacy, but her photo visibilizing the tension between labor and motherhood made her the lightning rod of the debate. There’s a tangible discomfort, on the one hand, of denying people their desire to have a biological child with the help of someone else. Queer couples, in particular, find themselves getting the short end of the stick: in India, they cannot legally marry, adopt, or conceive via surrogacy. But on the other, whose bodies are employed for the process? Elite surrogate babies in particular represent some uncomfortable truths about motherhood itself — one that indicts a global system of inequality that allows for some women to be, as critics call it, “wombs for hire.”

In 1988, Barbara Katz Rothman poseda question that cuts to the heart of the global politics of surrogacy: “Can we look forward to baby farms, with white embryos grown in young and Third World women?” Indeed, the high costs associated with surrogacy in first world countries have created a global supply chain of sorts — where parents from these countries employ women from India, Thailand, and others as “cheaper” options.

Countries like India and Thailand became popular surrogacy destinations because they cheapened the process for prospective clients abroad. Access to cheaper reproductive labor is a “function of unbalanced global structures of resource distribution, social exclusion, and economic inequalities that are rife in the contemporary global order,” say researchers Ademola Kazeem Fayemi and Amara Esther Chimakonam. This also means that surrogacy clinics in these countries turned it into a strict market transaction — optimizing the lives and bodies of surrogate mothers for the availability, comfort, and emotional baggage of wealthier clients. Among many practices they employed are pre-term cesarean births, so that the baby’s arrival is timed in accordance with the client’s needs.

Related on The Swaddle:

Fertility Clinics find Loophole in India’s Surrogacy Ban

To look at the implications of commercial surrogacy, a look at surrogate hostels shows how poor women in the global south are disciplined into perfect “mother-workers,” as scholar Amrita Pande puts it, to service elite national and international clients. The surrogate mother is one whose connection to motherhood is severed by contract, and whose body itself becomes the site of labor. They’re then regulated by hostels as an institution, in order to produce the “The perfect surrogate –cheap, docile, selfless, and nurturing,” as Pande adds.

Transnational commercial surrogacy then sorts people into reproducing bodies and “real” parents — and it does so by prioritizing the desires of a wealthy couple for “normative nuclear families complete with genetically descended children,” as scholar Sharmila Rudrappa notes. These “all shape the work experiences of surrogate mothers who are pumped with hormones, sequestered in surrogacy dormitories away from their own families and children, and almost always, cut open in cesarean surgeries in order for first world clients to achieve their own nuclear families replete with that priceless baby who nonetheless comes at a market price.”

These power dynamics are cemented by the cultural erasure of surrogate mothers. In almost all celebrity baby announcements, the surrogate is invisible — as was the case with Khloé Kardashian’s hospital photo. It turns commissioning couples into “true creators, progenitors of labor power that begets new life,” and those who perform the reproductive labor itself as “empty receptacles, mere body space that is rented,” Rudrappa adds.

Related on The Swaddle:

Global Coordination Needed to Make Surrogacy Laws Work for All

On the other hand, some scholars argue that the disciplinary functioning of surrogacy clinics are the problem — and advocate for treating surrogate mothers as workers whose labor creates value. Surrogacy is a new form of labor, subject to exploitation just as any other form of labor is. But it still remains unique: “Underpinned by inequalities of class, race, gender and geography, surrogacy is a complex form of reproductive labour that is intimate, emotional and embodied, much like other forms of paid body labour in the increasing commodification of ‘new’ sites and spaces of work,” note sociologists Madhusree Jana and Anita Hammer.

It would undermine the agency of surrogate mothers to cast them as victims, some argue — recognizing their rights would entail recognizing surrogacy as reproductive labor. This means enabling surrogate mothers to unionize, advocate for protections, healthcare, and other conditions of work that keep them safe, argues legal expert Pabha Kotiswaran. It would also mean going beyond conceptualizing surrogacy as a labor contract, as Kalindi Vora, researcher on surrgocay, notes.Many surrogate mothers view their labor as divine and thus use surrogacy as a site of resisting the dominant narrative about them.

Moreover, bans on commercial surrogacy, Rudrappa notes, only worsen the problem: they don’t stop commercial surrogacy from taking place, but push working-class women into further exploitation and precarity. Women are flown from country to country to escape jurisdiction concerns, with the clients and their babies prioritized at the cost of surrogate mothers’ safety.

But the debate doesn’t just end with birth. The labor involved in motherhood continues to be distributed unequally across class, caste, racial, and global lines. There’s a name for this: the “globalization of motherhood” itself. Under this paradigm, assistive reproductive technologies may end up furthering inequality — globalization and capitalism mean that advances in reproductive technology can only acrue to a few people, with others serving as instruments rather than benefactors.

Altruistic surrogacy, moreover, comes with its own set of problems. Regulations over who can be altruistic surrogates, and for whom, also remain fraught — with governments using these laws to reinforce cis-heteronormative family structures.

Still, separating reproductive labor from “mothering” labor complicates the conversation. Child reproduction and rearing have to be collective processes in order to free individual women of the baggage of motherhood. But over time, the process became one-sided — with a few people of means non-reciprocally accessing certain aspects of parenthood from others. The Khloé Kardashian photo, then, represents a vital conversation pertaining to feminism and motherhood: who gets to access reproductive labor, and at what cost?

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

It’s Okay: To Not Always Be There for Friends