How an Ancient Society Found a Way To Thrive in the ‘Worst Year’ in Human History

“We should take some solace in knowing that it’s possible to reorganize, to change, even deeply rooted aspects of societies.”

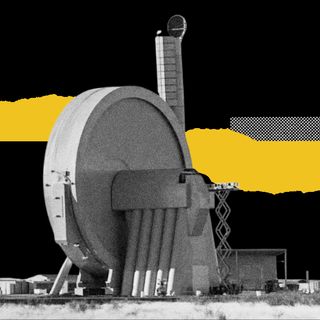

The years between 536 C.E. to 541 C.E., science has it, were among the worst to be alive for human beings. It makes the past two years spent under the shadow of a pandemic pale in comparison. A series of volcanic eruptions, which sent great clouds of fly-ash into the atmosphere, leading to a catastrophic chain of events, marked these years. This included perpetual darkness due to blocked sunlight, colder global temperatures, and crop failure.

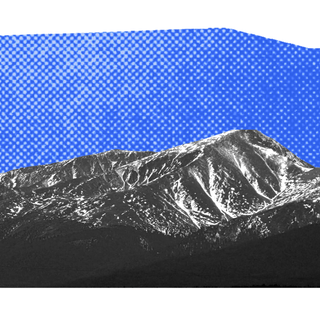

But even as various societies struggled to survive, the Pueblo society, a prehistoric Native American civilization, living in what is today Southwest USA, seemingly thrived. How they responded to an unprecedented global ice age ensured that they emerged from it as an advanced and flourishing cultural center for centuries. Looking at their lives can give us clues about what it takes to be a society that survives the worst of times.

A study published last week in Antiquityexplored how their survival came to be. Using carbon dating of food grains found from the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries, the team of researchers was able to uncover astonishing levels of adaptation among the Puebloan people. So much so, that the Hopi community — the living descendants of Puebloan people today — still utilize some of their ancestors’ techniques for farming in cold weather and turkey domestication.

While researchers have known for a while that there was a sudden population boom and demographic changes to the society, the new study provides important context as to why that was. Using food grains and other evidence excavated from the Colorado Plateau, researchers found that the Puebloans started out-growing farming-intensive crops in a more scattered way, and eventually advanced into becoming expert growers with only a short gap during the crisis. Similarly, housing structures saw a similar pattern, where construction activity saw an upswing at the end of the sixth century.

The secret ingredient, it would seem, is large-scale cooperation. The Puebloans were not always one, cohesive society — they started out as isolated bands of farmers and kin-based groups growing maize and beans, or otherwise hunting and foraging. Researchers surmise that as disparate groups of crops were failing, there was no choice but to band together to ensure the larger community’s survival. Their sharing of technology and ideas for how best to weather the crisis ensured that when it passed, the Puebloans became a more structured, organized society than they ever were.

Related on The Swaddle:

A 1,000‑Year‑Old Fossil is Challenging Sex and Gender Binaries in History

“Archaeological tree-ring and radiocarbon dates, along with settlement survey data suggest that extreme cooling generated the physical and social space that enabled early farmers to transition from kin-focused socio-economic strategies to increasingly complex and widely shared forms of social organization that served as foundational elements of burgeoning Ancestral Pueblo societies,” the paper states.

This transition was the key to ensuring that the Pueblo society continued to figure in ancient human history as one of the major societies for several centuries. As settlements moved closer together in response to the crisis, the cluster led to better knowledge sharing and technology. This is the story of how most civilizations expand, but the research shows how this was the case during — and arguably, due to — a major external upheaval.

The cold temperatures due to the global ice age spurred a “swift resettlement” — a change in population movement patterns — that allowed for the sharing of favorable socio-economic traditions. “The climate anomaly upended diverse, longstanding settlement systems on the Colorado Plateau by pushing population movements beyond the boundaries of established social networks,” the study says. “This generated a cultural milieu ripe for the renegotiation of distinct and long-held local traditions.”

For instance, farming techniques grew more sophisticated as communities moved closer to one another — farmers now grew crops in a wide range of places and conditions, testing to see which one worked. In other words, a willingness to rethink longstanding norms to adapt for survival, was an essential part of the process.

“Ancestral Pueblo people restructured … and thrived with this reorganized economic and political structure… cooperation at this scale was not common earlier in time, but quickly became the norm,” said Reuven Sinensky, an anthropology graduate student from the University of California, Los Angeles, and lead author of the study.

Amid our own devastating circumstances, not only do these findings provide insights into our history; they could also be the key to surviving and discovering our future. With the pandemic and the climate crisis threatening many aspects of society, understanding the link between cooperation and survival during adversity may ensure a future worth aspiring for. The findings have particular implications for how we might tackle climate-induced food security, and taking cues from indigenous knowledge may help us recover what we may have deemed to be lost. “We should take some solace in knowing that it’s possible to reorganize, to change, even deeply rooted aspects of societies,” Sinensky reminds us.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Ancient Single‑Celled Organisms May Have Helped Form Mountains on Earth