How Emotions Alter Our Understanding of Time

Our brain creates the illusion of time to either demand more of a feeling in a “short” period or less of it as a response to an event.

Just the other day, a friend casually referenced the year as 2019. It feels like 2019, so it must be 2019. It took two minutes for our heads to shake back into reality. “We’re three months away from 2022,” they said, evidently perplexed by a fact they knew but somehow forgot.

It is a curious thing to overlook two years of one’s life. This by no means is a consistent experience; two years may feel like two months for some, drastically longer for others. When Tiger King’s sequel was announced recently, a colleague wryly asked if the show came out last year or five years ago. There is no right answer here. Living in a pandemic has made this experience more acute. People wax poetic about the timelessness of living in a lockdown, listlessly wondering where the days went by.

Time is many things. Its philosophy and physics have tempted experts for centuries, so much so that the theory of time only grows. Our contention, however, is with the perception of time, a small aspect of it. The body and mind understand this construct in unique ways; interrogating this idea can also prod some mysteries of daily experience.

It’s easier to tackle the physiological part of time first. Where is time processed in our minds? New research that has made full use of functional MRIs has been able to show the origin. It is a single brain structure that processes time and an extensive network of neural areas that determine how quickly or slowly time goes. The concept of “before” and “after” also becomes evident only when a child turns four; before that, even though infants and fetuses recognize vocal rhythms, they cannot distinguish external voices from their thoughts.

Our internal timekeeping is also contingent on the circadian clock. Think of these as biological clocks, independent of sunlight or temperature, which regulate our inner sense of time and help any sentient being adapt to the 24-hour cycle. These are responsible for determining who is an “early bird” or “night owl.” It also decides our biological response to time. Bodies rely on signals, both internal and external.

The psychological aspect of time is where things get a little muddy. “The literature on time perception generally begins with Augustine, because he was the first to talk about time as an internal experience — to ask what time is by exploring how it feels to inhabit it,” Alan Burdick, author of Why Time Flies: A Mostly Scientific Investigation, wrote in the New Yorker.

Augustine and so many after him have drawn, thus: time is a “property” of the mind. For this reason, time is also at the whim of individual memories and emotions, making it wildly subjective. A simple example of memory deciding our perception of time: when you ask yourself whether one song lasts longer than another, you don’t measure the song if but something the length of the memory you associate with it.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Did March 2020 Feel Like It Would Never End?

Time seems maddeningly abstract for many reasons; most of it is because of the interaction between emotions and time perception. This interaction has led to the rise of a scientific field of its own: temporal illusions. One interesting theory is the “oddball effect,” a perception of time that becomes active during stressful situations. Psychological scientist Peter Ulric Tse and colleagues demonstrated this effect in 2004 showed research participants repetitive images flashing on a computer screen, followed by a single novel image. Although all the photos stayed on the screen for the same amount of time, participants reported that the oddball image seemed to last longer than the others.

When people experience unusual events, they tend to emphasize them and spend more time recording the wide range of things presented to them. For instance, someone will always take longer to read a book for the first time due to the overwhelming amount of information. Time doesn’t slow down; we take longer to make sense of it. This concept may very well apply to the pandemic days — when the dirge of information and uncertainty have made the flow of time impossibly slow.

The oddball effect has many relatives. The “kappa effect” is when people tend to overestimate the duration based on space; the “stopping clock effect” is when people stare at the second hand of a clock and think it’s not moving (oh, the allure of time standing still).

“These, and other illusions show that our brains construct something as basic as the experience of time passing – and that this is based on what we experience and what seems the most likely explanation for those experiences, rather than some reliable internal signal,” journalist Tom Stafford noted in BBC Future. “We don’t ever get to know time directly. In this sense, we are all time travelers.”

Even the prospect of rewards influences temporal illusions. The idea of something “good” or “bad” waiting for people at the end of a task can alter the perceived duration of time. That desired movie date with a friend once lockdown lifts dangles away in the distance as we move slowly towards it; on the other hand, the looming Monday makes weekends feel significantly shorter.

This also means stress and fear make time feel slower, further explaining how the experience carries a deep tinge of emotions. Contrarily, feeling like time is passing faster than usual corresponds with enjoyable experiences. James McKeen, a researcher at the Claremont Graduate University, coined the term “flow” to describe the experience of being so happily immersed in an activity — be it athletics, work, or a creative project — that all distractions are shut out. A similar idea is that of the “approach motivation,” In a series of experiments, psychological scientists Philip Gable and Bryan Poole examined “approach motivation,” when the drive to achieve goals or positive experiences resulted in a shortened perception of time. In a 2012 study, the researchers gauged this by showing participants images of geometric shapes, flowers, and desserts for an equal amount of time. The positive associations with desserts resulted in people saying the dessert picture was shown for a shorter amount of time.

Happiness has sort of a contradictory effect on time perception too. In some cases, when people have “awe-inspiring” experiences or generally feel more content and satisfied, the passage of time becomes easier to notice, and they feel more “in the moment.” Researchers were able to show this in a study where people interacted with animals or watched waterfalls. Nature and time perception are also closely tied; people perceived time moved more slowly in natural settings than urban ones.

Any emotional perception of time will raise how to be in time and how to live in the moment. Psychologist Marc Wittmann noted the duration of a felt experience is only between two and three seconds— as long as it takes for Paul McCartney to sing the words, Hey Jude. “Everything before belongs to memory; everything after is anticipation,” journalist Paul Bloom noted.

Time is the greatest mystery. Does it flow, or is it fragmented? What constitutes the present? Is time finite? As Burdick puts it: “Is now an indivisible instant, a line of vapor between the past and the future? Or is it an instant that can be measured—and, if so, how long is it? And what lies between the instants?” We know that the subjective experience of time’s passage shapes everything from our emotional memory to our sense of self.

The cultural legacy of time gives it a sentient quality. Time is the wisest counselor. Time heals; time races against us. Time flies by; time drags. The scope of human subjectivity is infinite, such that we have afforded multiple meanings to processing time.

My favorite time-related metaphor, which I told my friend after the 2019-2021 mix-up: “Where did the time go by?”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

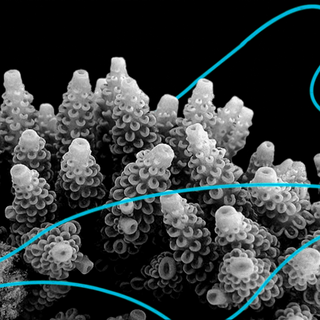

Algae’s Sex Lives Could Help Corals Survive Climate Change, Research Shows