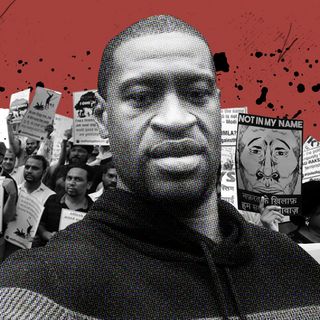

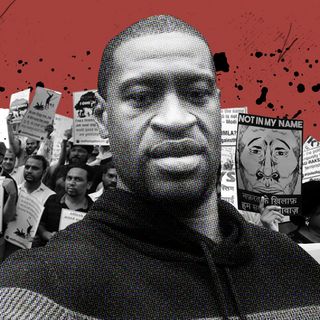

The United States is reverberating with the #BlackLivesMatter cries of outraged protesters taking to the streets after Minneapolis cop Derek Chauvin killed 46-year-old African-American man George Floyd by grinding a knee to his neck, pinning him to the ground for eight minutes and 46 seconds. Across the country, the police are escalating violence against BLM protesters and journalists by using tear gas to control crowds. Images coming out of these protests, unfortunately, are not new. The spectre of police officers rendering protesters immobile with tear gas has played out more times than we can count — from BLM protests in the U.S. to anti-NRC-CAA protests in India.

The thing is, tear gas is banned in warfare. As per the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993 — signed by most countries of the world, including India and the U.S. — tear gas is a chemical agent that is prohibited from use in wartime. But it’s somehow perfectly legal in domestic riot control, in which the police weaponises it against protesters.

Tear gas is usually available in liquid or powder form, commonly packed into canisters and used as aerosol sprays. When sprayed, the chemical compounds that make up tear gas diffuse into the air as fine droplets, which are easily absorbed through skin and eyes, or inhaled through the mouth and nose. Once inside the body, these chemicals permeate mucus membranes to cause severe pain that lasts approximately 30 minutes. When mixed with liquid, such as sweat or oil on a person’s skin, the chemicals in tear gas also become an acidic liquid that causes burning and pain.

The irritation tear gas causes to the eyes, mouth, throat, lungs, and skin, according to the U.S. Centers For Disease Control (CDC), manifests as excessive tearing, burning eyes, blurred vision and redness; it causes burning and swelling of the nose; in the mouth, it causes burning, irritation, difficulty swallowing and drooling; it causes chest tightness in the lungs, creates a choking sensation, wheezing and shortness of breath; it can also cause burns, rashes, nausea and vomiting. If exposed to tear gas in large quantities or for extended periods of time, an individual can develop glaucoma (eye condition) or even become blind, suffer severe chemical burns to the throat and lungs that lead to death, or experience respiratory failure also resulting in death.

Related on The Swaddle:

A Therapist’s Notes on the Mental Health Fallout of the NRC-CAA Protests

Tear gases are not benign, Sven-Eric Jordt, a professor of pharmacology at Yale University School of Medicine, tells National Geographic. They are “nerve gases that specifically activate pain-sensing nerves … Tear gases are very serious chemical threats.”

So, why does law enforcement around the world, from Turkey to Hong Kong, still use tear gas against civilians? Tear gas is often considered one the least lethal weapons the police have in their arsenal to control crowds or disperse riot-like situations. Jordt says, “law enforcement has to weigh the risk of tear gas injury of bystanders against gaining control in a riot situation, under the assumption that rioters break the law.”

Two issues here: First, tear gas is an “indiscriminate weapon,” Jamil Dakwar, director of the human rights program at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), tells Public Radio International. Because of its diffusive quality, there’s no way to control its deployment — “it doesn’t really distinguish between young people and elderly, the healthy and the sick, people who are peaceful protesters or those who are using violence,” Dakwar says. Second, tear gas is often generously deployed even in peaceful protest situations, which has signaled to experts that the tear gas has turned into a weapon to suppress protest in modern times — as seen in India when the police attacked students protesting the NRC-CAA — than control riots as it was first deemed to do.

Dakwar asks, “The question is, when do you deploy it? When do you resort to that?” He adds, “There has to be layers and layers of de-escalation — steps and actions taken by law enforcement — before you reach that point.”