HPV Test More Effective Than Pap Smear, But No Replacement

Combined, the tests make cervical cancer screening much more effective (if still uncomfortable).

Recently, discussion of cervical cancer has focused on the HPV vaccine, and its proven role in preventing the disease. But international recommendations say its effectiveness wanes if the vaccination course is started after age 21. (The HPV vaccine should be administered to both boys and girls, starting at ages 11 to 12, for maximum coverage.)

So, where does that leave the generations of women who missed out on the vaccine?

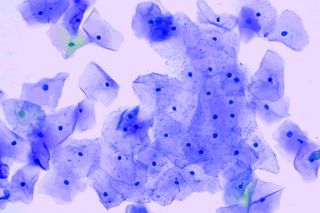

Until now, it’s left them with the Pap smear as the only way to identify abnormal cervical cells, some of which may be benign or may be the kind of precancerous cells that a human papillomavirus infection can cause. But a new study of 19,000 women over four years, published in JAMA, has found HPV testing leads to the diagnosis of precancerous cervical cells earlier and more frequently than Pap testing. Some experts are heralding the finding as the beginning of the end of the Pap smear, an uncomfortable, intrusive procedure that cannot distinguish between abnormal tissue and actual precancer.

“It’s fantastic,” Dr Kathleen Schmeler, a gynecological oncologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center, told The Washington Post. “What this shows is that you could potentially do just the HPV test and move toward getting rid of the Pap test.”

Other doctors are less enthused. There are limitations to both tests, says Dr. Devika Chopra, a gynecologist at the Hope Clinic in Mumbai.

“HPV testing will tell you whether the person has been infected with the disease,” says Dr Chopra. It won’t detect an active infection (active HPV infections are notoriously difficult to identify; most people don’t realize they’ve ever had the infection), but knowing whether a person has been infected at all is useful for identifying who is at risk and who should be tested further for precancerous cervical lesions.

By contrast, Pap smears detect abnormal tissue. “It will tell you if there are changes [to cervical tissue] that are likely cancerous, or if the cells are not normal,” Dr Chopra says. “Following that, there are certain more tests that you would have to do.”

“I don’t think [the HPV test] will ever replace it,” Dr Chopra adds. Instead, she says integration is the way forward; doctors should make use of both tests, rather than one alone.

The study supports this. The HPV tests picked out 25 women, who would go on to have abnormal results, women that Pap tests would have missed — but the Pap tests also spotted three cases that HPV tests would not have flagged.

This may partly be due to the visual element of a Pap smear. In some cases, “the doctor can see whether it’s been infected or no. You can come to see visually also whether a cervix looks normal or abnormal,” Dr. Chopra says. “You have to look at the cervix. Every gynec should look at your cervix. For a sexually active woman, it’s necessary.”

Necessary — but not comfortable; Dr Chopra says both an HPV test and a Pap smear require feet up in the air in stirrups, and a speculum.

Even if the HPV test does not fully replace the Pap smear, it’s already likely to be as much of a game changer in detecting cervical cancer as the latter test has been since its introduction in the 1940s.

That is, until uptake of the HPV vaccine becomes more widespread, virtually eliminating the possibility of cervical cancer altogether.

“The HPV vaccine is a good vaccine,” Dr Chopra says. “I give it to most of my patients.”

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Feeling Young Might Mean Your Brain Is Aging More Slowly