Hungry For Education

Why are the country’s “best” universities the most anxious about food?

.png?rect=0,565,3375,2246&w=320&h=213&fit=min&auto=format)

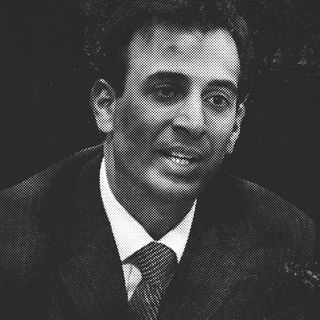

In 'Politics of Plates,' Vinay Kumar traces stories of history, politics and resistance through food.

Who Owns the Mess Halls?

"The word (breath) is another means of contact. That is why the profane is forbidden to address the sacred things or to utter them. For instance, the Veda must be uttered only by the Brahmin and not by the Shudra. An exceptionally intimate contact is the one resulting from the absorption of food."

*

If you want to know the story of education in the country, look at the food in the mess halls. Student roll call lists show who is enrolled, but dining halls show who was truly meant to enrol.

Last month, a student at IIT-Bombay was fined a hefty fee of Rs. 10,000 for protesting against vegetarian separation in the dining hall. The institute’s disproportionately harsh response to a peaceful act of protest is telling of the fact that notions of food “purity” in the country extend far beyond respecting individual preferences.

Pushing for vegetarian-only segregation is a manifestation of the same casteist practices that pervade the rest of the education sector in the country.

Food is political. But political discourse around food in the country still largely revolves around beef. The IIT Bombay incident is an example of why we need to understand the food problem with more nuance. It speaks to an unspoken selection criteria at India’s best universities: caste. The writing has been on the wall for a while. The Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA) at the University of Hyderabad even prepared a 7-page report on discrimination in the PhD admission process.

Where food is concerned, the discord often boils over into violence. The violence over the Beef and Pork Festival in 2012 at JNU, at Osmania University in 2015, and IIT-B in 2017 are all markers of the charged nature of food. In IIT Madras, a student physically assaulted another (with beef!) for protesting over beef-bans in the country. Dry fish, bamboo shoots, and dog meat have all been met with similar reactions, illustrating the violent prejudice in academic spaces over cultural differences. But these conflicts didn’t come out of a vacuum.

Secular Segregation

“There are seventy-two single rooms and eight mess rooms, each with its own store and kitchen so that members of different races and castes can form separate groups, each observing its own customs.”

*

In 1943, at the Indian Institute of Science (IISC) Bengaluru, a restless churn was underway on campus because of a proposed change to the mess system – a plan to shut down the eight messes (there was even a separate kitchen for the sole Muslim student) and replace them with a common dining hall. This provoked an alleged hunger strike and various student protests. As far as the students were concerned, the existing norms spoke to a liberal, secular culture for a liberal, secular country.

Separate but equal. Except, some more equal than others. That was the preferred status quo.

The primary issue at hand for the students, it seemed, was food “pollution” that would result in a mixed dining room. This essentially speaks to the anxiety around falling from one’s place in the caste hierarchy. As the IISC turmoil escalated, a representative from the Tata family, a significant funder, wrote to the institute threatening to cut funding.

Money in a science institute controls everything from research grants and equipment to basic amenities like hostels, food, and housekeeping. However, good funding also means that the funders decide who is entitled to their money’s worth. For example, the cafeterias of IIT/IIM often include a mess that caters to three meals and a snack with a series of shops and cafes like Cafe Coffee Day, Baskin-Robbins, and Domino’s, among other outlets. While underfunded central/state universities struggle to ensure that the rice and roti they serve is cooked.

Why are the country’s “best” universities the most anxious about food? Why are spaces of supposed scientific temper concerned with notions of “pure” vegetarianism? Meat is just an “acceptable” stand-in for the anxiety around who belongs in these premier academic institutions. It’s telling that vegetarianism seems to be the preferred food practice in a country where only 30% of its population is vegetarian. These were meant to be “elite” institutes, selective in their intake. And the food politics say the quiet parts out loud: the desired elite is specifically a Brahmin, vegetarian elite.

“[I]nter-dining and inter-marriage are repugnant to the beliefs and dogmas which the Hindus regard as sacred,” explains Dr B R Ambedkar in “Annihilation of Caste.” From his work, it is evident that vegetarianism is a practice adopted by Brahmins to re-establish their failing supremacy and maintain their place in the caste hierarchy. In other words: Brahmins fashion themselves as the intellectual elite. Food segregation is how they can still – acceptably – assert their exclusivity.

The ideal or preferred candidate at any institute is the one for whom there is built-in scaffolding and institutional support. Food is essential, intimate. Food cultures are markers or indicators of one's caste and class. When institutions are sculpted to recreate a Brahminical household, only the Brahmin male student feels at home. But educational spaces need to be conducive for academic endeavours for all; instead, they are spaces that recreate caste hierarchy and limit student mobility – and emotional security.

How much control do individuals and institutional heads hold to ensure all students’ well-being? There have been no visible attempts since the 1940s to reimagine the contiguous space of the mess hall as one to erase social structures. Science institutes offered a model that has been recreated and left unquestioned. On paper, students from all backgrounds have the right to apply, attempt exams, and enrol. But once inside, the mess halls – posited as one of the great “common” spaces – make it clear who was really meant to be there, by design.

Meat in Whose Mouths?

“It is not sinful to eat the meat of eatable animals, for Brahma has created both the eaters and the eatables.”

*

Many Savarna students do eat meat, and universities offer “non-veg” as part of the menu. What explains this inconsistency, where meat shifts in and out of the liminal space between purity and pollution, fragrant and foetid? One of the more important of the eighteen Smritis of Hinduism, The Manusmriti, says eating meat isn’t a sin if it’s the right animal’s meat. Meat-eating Brahmins historically have found excuses to accommodate their meat-eating.

Here is the real issue: “A Shudra is unfit to receive education. The upper varnas should not impart education or advise a Shudra” (Manu IV-78 to 81). Meat for me and mine, but not for thee and thine.

Many private universities don’t even make any pretence of inclusivity. At “vegetarian” private universities, meat is not allowed on the grounds. Students are often found outside the gate eating meat – and that’s if they can afford it on top of the already prohibitive private tuition fees. There are no prizes for guessing who these students are. Where there are no segregation norms – availability of meat inside versus outside the campus space turns into its own form of segregation.

As Prof Rituparna Patgiri writes, “Hostel food is closely tied to the concept of belonging to a community.” Private hostels are headed in a direction to segregate and separate students. There is no space for a community to grow. Segregation – by way of intra-mess rules or campus walls – form in and out groups on campuses. Meat is almost immaterial, even if it is in the name of meat that students are sifted and sedimented away from one another. As Dr. Ambedkar illustrated, caste isn’t a physical separation but a belief system enabled by unwavering and unquestioning faith.

The fact that universities view their role as educators only inside the classroom makes them complicit. Dr Etienne Rassendren talks about how, if an institution doesn’t consider its marginalised student’s needs – like food, travel allowances and clothing – outside their tuition, it can’t help them access the education they want to provide. In other words, education isn’t just the classroom; it is also the material security essential for learning. Take the rare example of a policy recognizing this: In 2014, St Joseph’s University in Bangalore started a lunch scheme for students with economic disadvantages. They could sign up to receive lunch coupons to claim at the cafeteria. This is an example of student- or academic-centric policy to ensure that students are able to focus on their academics and not their growling stomachs.

From a nutrition standpoint, many have pointed out why meat is essential – and acts as a leveller for those who do not have the cushioning of healthcare or less exposure to pathogens. “Pushing [children] to eat unusual [‘pure’ vegetarian] foods because they are ‘healthy’, economical or good for the climate shows a certain insensitivity,” writes Dr Sylvia Karpugam. But meat changes its meaning according to who has access to it. In the mouths of the privileged, it is subversive; in the mouths of the marginalized, it is seditious.

The Heart of Resistance

“Caste is not a physical object like a wall of bricks or a line of barbed wire which prevents the Hindus from co-mingling and which has, therefore, to be pulled down. Caste is a notion, it is a state of the mind. The destruction of Caste does not therefore mean the destruction of a physical barrier. It means a notional change.”

*

Stories of food on campus are always ones of alienation and separation. And then you hear about a story that’s like an unexpected badam in your payasam. In January 2017, as protests over Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder stormed the country, students at University of Hyderabad gathered agitated and protested on the thousand odd acre campus. The administration chose to lock the students inside the campus when the student agitation grew. Nobody could leave. Messes were locked and shut. And the food had run out. Agitations end in moments like this, but when students from Osmania University, English and Foreign Languages University, and other places brought them packed biryani and dropped it over compound walls, it ensured that at least the fight could go on. Amid open administrative hostility, the student body realised they weren’t alone and that it wasn’t just their struggle. Students across many campuses in the country stood with them in solidarity.

This was a learning moment for institutions and state and central governments – and it began with the act of breaching boundaries around food. This solidarity came from the shared values and hopes for a better future for everyone. It stands testament to what can be achieved if the arbitrary delineations around food are abandoned in favor of community.

The content and opinions expressed are that of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Azim Premji University.

Vinay Kumar is a lecturer at Azim Premji University Bangalore. He's been a freelance journalist, translator and photographer previously and written for various media outlets. He received his Master's degree in English from the University of Hyderabad.

Related

Why Bangladesh’s Ongoing Garment Workers’ Strike Is a Feminist Issue