The Intriguing Link Between Common Infections and Eating Disorders

A new study found that people with infections such as meningitis were more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia and bulimia.

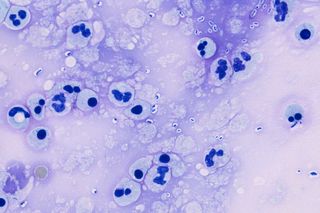

After several isolated incidents of children developing eating disorders upon contracting a streptococcal infection (caused by the bacteria streptococcus came to light, a group of researchers from the U.S. and Denmark set about to investigate the curious link between the two: infections, which are physiological ailments, and eating disorders, which are mental illnesses.

The findings of the study, published in JAMA Psychiatry, suggest that infections might, in fact, lead to eating disorders in some people. More specifically, the study found that hospital-treated infections and less-severe viral or bacterial infections treated with anti-infective medicines are associated with increased risk of subsequent anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

For the study, Lauren Breithaupt,Ph.D., lead author of the study and a clinical psychologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, along with her colleagues, examined the medical histories of 5,25,643 adolescent Danish girls born between 1989 and 2006 to see if they had ever been hospitalized for, or given an anti-infective medicine for infections such as rheumatic fever, strep throat, viral meningitis, or influenza. The researchers also looked at how many of these girls had been diagnosed laterwith an eating disorder in a hospital, outpatient clinic, or emergency department setting.

A link immediately appeared: Teens hospitalized with severe infection were 22% more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia, 35% more likely to be diagnosed with bulimia, and 39% more likely to have an eating disorder that doesn’t quite meet the criteria for either, as compared to girls who were not hospitalized with any infections. Further, girls who were prescribed anti-infective medicines to fight off viral or bacterial infections were 23% more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia, 63% more likely to be diagnosed with bulimia, and 45% more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder not otherwise specified, compared with adolescent girls who did not have infections that required anti-infective medicines. The researchers also found that the girls were at the highest risk of being diagnosed with an eating disorder within the first three months of contracting an infection.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Unique Factors That Contribute to Eating Disorders in India

Science is yet to understand why infections may spark eating disorders in some people, but the leading theory, as told by Breithaupt to The Atlantic, is that “either the infection itself or the antibiotic used to treat it might be disrupting the patient’s gut microbiome, the collection of microorganisms in the intestine that plays a role in health and disease.” This disruption might change the neuropeptides — protein-like molecules used by neurons to influence the body’s activities, including food intake and metabolism — circulating in the gut. “Because the gut communicates with the brain, the quantities of neuropeptides circulating in the brain might then change, as well. That could, in essence, make people think differently about food or their body,” Breithaupt said.

Another theory is that when the body contracts an infection, its immune response produces antibodies to fight the invader. Sometimes, these antibodies end up attacking our own cells. In the case of eating disorders, The Atlantic reports, scientists suggest that the antibodies target the appetite centers of the brain, which may make a person think they are less hungry than they actually are. Previous research has already established this link: three-quarters of anorexic or bulimic women examined carried blood antibodies targeted against appetite centers in their brains. Only 16% of those without eating disorders had such antibodies.

In the end, we are left with more questions than answers. Is the link between infections and eating disorders causal, with 100% certainty? If yes, what is the exact mechanism? And, why aren’t all people with eating disorders those who have dealt with infections recently? Alternatively, why doesn’t everyone with an infection develop an eating disorder? What are the risk factors?

Scientists are yet to delve deeper into this newly found link, but one thing is certain: If confirmed, these findings can not only radically change the way eating disorders are treated (by checking for any lingering infections), but they can also change how eating disorders are perceived in our society, in which mental illnesses are as stigmatized as they are misunderstood. Patients with eating disorders who are attacked or dismissed for supposedly just ‘wanting to be thin’ or for being so vain as to starve themselves are less likely to be condemned if the underlying cause is found out to be, for instance, pneumonia. Speaking to The Atlantic, Jim Morris, Ph.D., a professor at Lancaster University in the U.K., said: “We say disease is due to biological factors, social factors, and psychological factors all interacting together. Well, it works with psychiatric disease as well.”

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Related

The ‘Bliss Point’ Is How Food Companies Ensure You Can’t Have Just One French Fry