Men Find Wearing Masks ‘Shameful, Not Cool and a Sign of Weakness’: U.S. Survey

The only way to combat this notion is to challenge the underlying masculinity norms that prevent men from caring for their well-being.

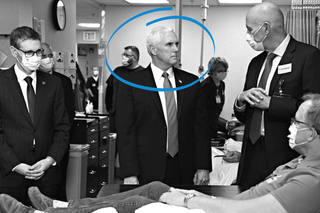

Ben Affleck smoking in a face mask. U.S. Vice President Mike Pence going maskless while visiting with coronavirus survivor. U.S. President Donald Trump flat out refusing to wear a mask. These images throughout the Covid19 pandemic have signaled the resistance of certain demographics to don protective masks that curb the aerosol spread of the novel coronavirus. A recent U.S.-based survey of 2,500 people shows this demographic is comprised mostly of men, who seem to think wearing a mask is “shameful, not cool and a sign of weakness.” Researchers also found the men surveyed seemed to think they wouldn’t be seriously affected by Covid19, which lulled them into a false sense of security, in turn exacerbating their aversion to masks — despite evidence that shows men are particularly susceptible to the coronavirus.

“With regard to gender, it has been postulated that women are generally less willing to take risks and are thus more compliant with preventive behavior than their male counterparts,” study authors from Middlesex University, U.K. and Mathematical Science Research Institute, U.S., wrote. “Study after study has shown that men are much more likely than women to engage in behaviors that are bad for their health,” according to Harvard Health. “More men than women smoke and drink excessively. The unbelted car driver or passenger is more likely to be male, as is the person who skips routine health screenings.”

Related on The Swaddle:

The Men Helping Other Men Challenge Toxic Masculinity

The phenomenon of men not taking necessary precautions to ensure a cautious, healthful approach toward their wellbeing is not new. It’s well known that adherence to traditional norms of masculinity is associated with reckless behaviours, aggression and violence, which is detrimental to the health of not only men, but also to the health of people around them. Healthful behaviours that prioritise prevention, caution and care, therefore, often fall outside of the ambit of these norms. The path to change this phenomenon, however, is not easy — society still penalises men for deviating from traditional norms of masculinity, which makes communicating public health policies to men all the more difficult.

A common approach that has been used throughout history to tackle this problem is to make public health outreach gender-conscious. When appealing to men, this often meant delivering public health information laced with masculine connotations. As far back as 1918, during the influenza pandemic and World War I, public health circulars had a “masculine slant” which tackled “masculine resistance to hygiene rules associated with mothers, school marms, and Sunday school teachers,” according to a paper assessing the impact of public health in the early 20th century, published in Public Health Reports. These included “a soldier considerately turning away from his comrades to cough into his handkerchief” and “an older man labeled ‘the public’ thrusting a hankie at a sneezing boy, asking that he ‘do your bit to protect me!’” The new messaging embodied a “more modern, manly form of public health, steeped in discipline, patriotism, and personal responsibility,” the paper states.

This approach has been used widely since then, effectively shaping public health policy targeted toward men. If doctors and health officials are more attuned to masculine attitudes and norms, they might be able to get through to men better, James Mahalik, a Boston College psychology researcher, tells Harvard Health, which adds, “If a man believes that eating fruits and vegetables is ‘eating like a woman,’ he might not do it. But if it’s presented as a way to help him succeed at work and give him more energy, he might.” Health policy that focuses on a certain male vulnerability is not likely to succeed, but one that’s worded around preserving some aspect of masculinity can make men engage in healthful behaviors.

For example, a Southeastern Virginia, U.S.-based sexual health campaign, called Man Up Mondays, asked men to “man up” after a weekend of risk-taking sexual behaviors, in an attempt to increase the percentage of men who seek STI testing. By including colloquialisms such as “man up” that reinforce masculine ideals of courage and strong-will in their advertising campaign, the program resulted in a 200% increase in the number of men that got tested for STIs, according to a 2014 paper published in the American Journal of Public Health.

Related on The Swaddle:

Masculinity Contest Culture In Science Disadvantages Women

However, in leveraging gender norms to instill healthful behaviours in men, public health policies also run the risk of continuing the same problematic gender norms that created such a phenomenon in the first place. They can contribute to “narrow and constraining forms of masculinity” — hegemonic masculinity — that give importance to certain masculine traits and paints them as positive. This can then lead to worse mental health outcomes, the 2014 paper states. “While ‘man up’ is used as messaging in an intervention to encourage STI testing, it can also draw upon existing colloquial calls to be a real man — take on more sexual partners — stand up to perceived disrespect from others by using violence – or not use a condom,” it adds. In such cases, a gender-conscious approach can become a gender-reinforcing, and in turn, a gender-damaging, one.

The need of the hour is a gender-transformative approach, especially as the world deals with the life-threatening coronavirus pandemic that does require everyone, even men, to follow public health policy guidelines to keep themselves, and others around them, safe. “Gender-transformative approaches do not rely on adherence to harmful gender norms and instead aim to challenge the inequitable system of gender norms,” the 2014 paper states. Such an approach would not succumb to getting men to follow rules delivered in the masculine messaging they understand, but would instead challenge the idea of masculinity itself.

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

Woe Is Me! “My Friend Is Texting A Much Younger Woman. Do I Intervene?”