32,645 Indians, across 25 states and five union territories, have admitted to having live, exotic species in their possession following a government disclosure scheme announced last year.

People have declared possession of exotic bird, reptile, amphibian, and mammalian species, such as kangaroos, lemurs, rhinoceros iguanas, macaws, and lovebirds, among others. West Bengal topped the list with the highest volume — 30% — of declarations, followed by Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra, IndiaSpend reports.

The disclosures include information about the possession of endangered species, too, like the black-and-white ruffed lemur endemic to Madagascar, and the beisa, an antelope endemic to eastern Africa.

Last June, while the world was caught in the eye of the global health crisis caused by a zoonotic disease, the central government issued an advisory introducing a voluntary disclosure scheme urging citizens to declare possession of any exotic, i.e., non-native, live species.

“This is the first step in controlling the illegal pet trade. … Exotics are a major problem for us because of invasive species and possible ecological imbalance if they are released in the wild,” Jose Louise, who heads the wildlife crime prevention unit for the Wildlife Trust of India, explained to The Hindu at the time.

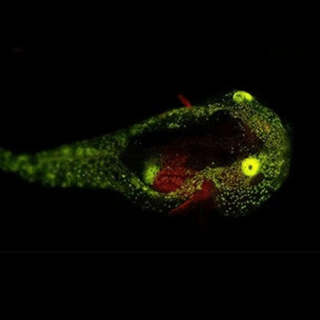

Ecological imbalance can be triggered by exotic species invading local ecosystems — as seen already in the case of invasive, non-native species of trees erasing endemic biodiversity across the Western Ghats. But non-native animal species also pose the threat of zoonotic diseases.

Related on The Swaddle:

African Cheetahs Will Be Reintroduced to India 70 Years After Local Extinction

Under this ‘amnesty scheme,’ individuals who declared acquisition or possession of exotic species within the six-month window of June to December 2020 cannot be prosecuted for the same. But some reports have pointed out a lack of clarity on whether the individuals who have made disclosures can be prosecuted over the means or manner of acquisition or possession by authorities outside the environment ministry, such as revenue intelligence bodies.

But what is known is that once the six-month window has closed, the government has the liberty to introduce a regulatory, and even penal, code governing the trade of exotic species.

“The major reason to do this is to regulate the trade because zoonotic diseases are linked to wildlife. With this advisory, we will know how many such exotic animals are there in the country,” Soumitra Dasgupta, inspector general of the environment ministry’s wildlife division, told Down To Earth last year after the scheme was announced.

Dasgupta explained the exercise was an endeavor to bring exotic animal imports within the purview of forest departments — to help keep the authorities “in the loop.”

Experts also believe the advisory could potentially act as a disabler of the wildlife trade in India since, until now, forest officers couldn’t control the trade because non-native species weren’t protected under India’s Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.