New Three‑Parent Fertilization Technique Could Help Trans Men Have Children

While not yet available for clinical use, the technique bolsters our understanding of reproductive rights and technologies.

While the world grapples with rollbacks on reproductive rights, there’s a scarcely discussed aspect of it: reproductive rights of trans people. The issue is arguably even more fraught when it comes to trans men who wish to have their own children. The process typically involves invasive and dysphoric fertility treatments that clash with gender-affirmative treatments. But a new advancement could change that.

Researcher Antonia Christodoulaki from Ghent University in Belgium found evidence of a three-parent fertilization technique that could help trans men reproduce sans traditional IVF treatments. Presenting her findings at the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, Christodoulaki said that the method could help affirm trans men’s rights to have their own children. “Every person should have the right to reproduce,” she told the MIT Technology Review.

At present, trans men who wish to have children undergo treatments that stimulate their ovaries to release several eggs at once. This requires them to either pause gender-affirming treatments like hormone therapy, or postpone it until their eggs are collected and frozen. Testosterone — the hormone administered as part of gender affirmative treatment — can hamper egg production.

While this method works on a technical front, it can be dysphoric to experience the side effects of fertility treatments that stimulate ovaries — these include cramps, breast tenderness, and others. Moreover, the process of collecting eggs is laden with medical processes that over-emphasize the gendered body — like vaginal exams.

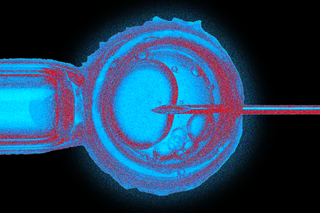

The new technique then involves a combination of two processes that are already practiced by many clinicians. It works by removing a portion of the ovary altogether, and administering fertility treatments outside the body — in other words, coaxing egg production from the portion of the ovary that’s removed. Next, the researchers tested the fertility of the eggs of trans men as compared with cis women, by fertilizing them with sperm. Results showed a lower success rate of fertilization and a lower survival rate of fertilized embryos with trans men’s eggs than with a cis woman’s.

Here is where the three-parent technique comes into play. It involves transplanting the nucleic material, containing DNA, from trans men’s eggs into cis women’s eggs where the same material had been removed. This is a result of the hypothesis that the problem lay in the cytoplasm — or the cell contents outside the nucleus. The resulting embryos were found to survive more than five days at a greater rate than trans men’s embryos. They’re also the product of reproductive cells of three people: eggs from two different people, and sperm.

Related on The Swaddle:

What a Transgender‑Friendly Health Care System Would Look Like

The method isn’t yet available for clinical use, but it could revolutionize reproductive health for trans men — importantly, for the way it recognizes dysphoria as an avoidable health issue. Even though recent studies have shown that trans men’s ovaries can yield eggs at a rate comparable to cis women even after transitioning, it involves stopping testosterone for months at a time. “[T]he thought of stopping testosterone or going through hormone treatments is very daunting for them, so they frequently will not pursue it because of that,” according to Dr. Samuel Pang, a reproductive endocrinologist from Boston IVF. This means that many trans men who may have otherwise wanted to have their own children are opting out of doing so — and medical barriers to a safe, affirmative way to do so, are a big reason why.

Moreover, three-parent babies already exist. A process called mitochondrial transfer involves replacing mitochondrial DNA from a parent with a genetic disorder with healthy mitochondrial DNA from a third person. “This term is slightly misleading, as the child does not have an equal proportion of DNA from each parent. Rather, the majority of the child’s DNA is from his parents, with only a small fraction coming from the mitochondria of the donor egg or third parent,” a Harvard University blog noted. But while this particular procedure is fraught with ethical concerns — pertaining to eugenics, for instance — the three-parent fertilization method doesn’t have the same issues. For one, it doesn’t swap DNA for a gene-editing purpose; the intent, rather, is to replace faulty cytoplasm in trans men’s eggs.

The procedure, if it can be implemented, then expands the scope of reproductive rights to account for the diversity of healthcare needs across individuals. At present, many trans men and non-binary individuals already report feeling excluded from conversations about reproductive rights. It’s a frontier that reproductive science is also beginning to catch up with. One review studied the case of Sam, a trans man who delivered a stillborn baby on account of practitioners ignoring his abdominal pain as a non-urgent condition — since they registered him as a man. “Inclusive clinical care and research that addresses the relationship between sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and social determinants of health are crucial to achieving health equity,” it concludes.

When we begin to understand reproductive rights as fundamental to the bodily autonomy of all human beings, experiences of pain and overall wellbeing begin to be included in the conversation. The new technique that can reduce dysphoria among trans men seeking to have biological children then affirms the importance of seeing reproductive rights as beyond the realm of procreation — but expands its scope into one that’s rooted in bodily autonomy and freedom.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Microplastics, ‘Forever Chemicals’ Have Contaminated Rain Beyond Safe Levels, Shows Study