Patient Feedback Could Improve Childbirth Experiences at Hospitals

In whisper networks, new mothers report a dissatisfaction with care that seldom gets back to hospitals.

In March 2017, Karen Alfonso was registering to give birth at private hospital in Mumbai. With the head nurse, she and her husband discussed the room facilities and charges. They were given a list of things to buy, one of which was formula — just in case. “They told us we could return it if we didn’t use it,” she remembers. At no point did anyone mention her husband would need to take a course in order to be present for the birth.

But later, “when it comes to delivery, they tell my husband he couldn’t be in the room because he hadn’t done the course,” Alfonso says. “Even the gynec[ologist] told the nurses to send him in, but they didn’t convey that to him. They didn’t tell him the gynec[ologist] had called him in.” While Alfonso, wracked with labor pains, was giving birth, her husband sat unhappily with other family members in a waiting room.

After delivery, “while I was getting stitched up, [the nursing staff] fed my son formula. I had no clue about all of this,” Alfonso says. “They just decided to feed him on their own terms. Considering how important the first feed is, it was just very dishonest and disappointing to know they did that without my consent.”

Along the spectrum of dissatisfying childbirth experiences, Alfonso’s is a relatively benign one — a far cry from the flagrant physical and emotional abuse of lower-income women found in the labor wards of India’s public hospitals. But it represents a common experience that Indian women are coalescing around and speaking out against — the feeling that hospitals are not taking seriously the rights and wishes of mothers during childbirth.

“I didn’t also realize how big this thing is,” Alfonso said, referring to hospitals’ practice of feeding a newborn formula before allowing the mother to breastfeed. “Much later, when I joined breastfeeding support groups, I saw that this was a trend.”

The reasons for this disregard range widely — from patriarchal norms that diminish women’s experiences and rubbish them as ‘complaints,’ to the poor oversight of India’s sprawling health care industry. But it largely boils down to: you can’t fix the problems you don’t know about. And a lack of clear lines for communication between new mothers and hospitals leaves one side helplessly angry, and the other blissfully unaware.

“I tell all of my friends who are going to be moms that this is what happened to me — watch out.”

Alfonso admits she didn’t raise her grievances with the hospital at the time of her delivery. She and her husband worried any protests would be reflected in poor care from hospital staff. Alfonso confided her dissatisfaction in her obstetrician — “She was really angry about the formula. She [had] checked my breasts. She saw that I had milk.” — but individual doctors are constrained in their advocacy for patients by their need to maintain access to hospital facilities.

Two years later, Alfonso still hasn’t approached the hospital with her concerns.

“It felt like a he-said-she-said situation,” Alfonso said. “I don’t know how much they would’ve listened to me, or taken my feedback. I mean, who do I [even] meet? The head nurse was the main person who didn’t tell us about the course.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Antenatal Classes Give Many Women Comfort; Information Is A Bonus

Around the same time Alfonso gave birth, patient-hospital communication was coming under the microscope. Media reports of grieving relatives attacking doctors abounded. And doctors complained of being judged on subjective standards by patients who didn’t understand the complexities of clinical care. Smaller, less urban and underfunded hospitals typically lacked transparent methods of feedback. And while many bigger and/or private hospitals offered patients feedback forms, the questions were more about satisfaction, rather than quality, which meant the feedback wasn’t really actionable, says Anne Reijns, commercial director of Together For Her, an social enterprise that works toward improving post-childbirth feedback between women and hospitals.

Working off of childbirth guidelines issued by the World Health Organization and the Federation of Obstetric and Gynecological Societies of India (FOGSI), the organization developed a set of objective, yes/no indicators of good care aimed at standardizing both patients’ and hospitals’ expectations:

- On-time admission. E.g., when a woman goes to the hospital in labor, is she checked by hospital staff or a doctor within the first 10 minutes of arriving?

- Cleanliness. E.g., in the place where she has her delivery, was it clean?

- Privacy during labor/delivery. E.g., was she covered with a sheet? Was the door closed to respect her privacy?

- Skin-to-skin contact after delivery. E.g., was the mother able to have skin-to-skin contact (a practice with many known benefits) with her child immediately after delivery?

- Early breastfeeding. E.g., was breastfeeding initiated in the first hour after delivery? If no, why not – was she or the child unwell? Or was she not allowed to try?

- Respect and courtesy. E.g., was she treated with respect and courtesy by doctors and hospital staff?

- Emotional support. E.g., was the mother given or allowed to receive emotional support through labor and delivery?

- Postpartum education. E.g., before discharge, was the mother informed about postpartum complications and danger signs for both her and her child?

- Family planning counseling. E.g., before discharge, was she given family planning counseling?

The organization’s post-birth surveys have been implemented in around 1,000 private hospitals, mainly in the T2 and T3 urban centers of Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. And an impact review conducted by the organization earlier this year has found a payoff: When the organization launched its survey, on average only 20% of women delivering at any given hospital in its program reported skin-to-skin contact in the first moments after birth. Now, that number is closer to 70%. Hospitals in their program are also increasingly introducing early breastfeeding, compared to two years earlier. There’s still a gap, Reijns acknowledges, but she says the review suggests that improving and enabling communication between women and hospitals is part of improving care.

It’s the kind of avenue for direct communication Alfonso wishes she could have had. Instead, since giving birth, she says she has warned countless friends and acquaintances through the whisper and WhatsApp networks of pregnant women. It may not actually change hospital practices, but she hopes it will spare other women, in a moment of ultimate vulnerability, the frustration, and helplessness she felt. “I tell all of my friends who are going to be moms that this is what happened to me — watch out.”

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

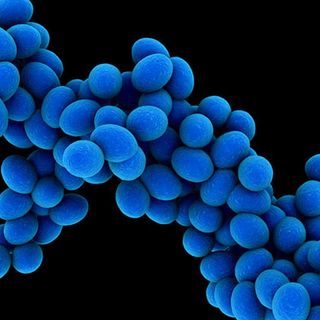

Indian Newborns Are Dying of Antibiotic‑Resistant Infections