People Who Are Homeless Are Unfairly Criminalized, Suggests New Study

A home offers economic and social mobility — both denied to marginalized people who are more likely to come in contact with the criminal justice system.

In 2009, researcher Sylvia Walby wrote of crises, and the ways they deceive us. “Crises are both ‘real,’ in the sense of actual changes in social processes, and socially constructed, in the sense that different interpretations of the crisis have implications for its outcome.”

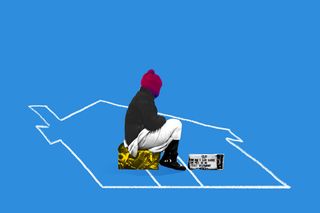

The home, and the absence of it, are sites of crisis too. Homelessness is growing to be a feature of the modern urban landscape; as cities grow, the rights of people to claim space in these development utopias dwindles. Much of this is justified through myth-making about criminality and deviance: if people are destitute, they must have led themselves there, goes the popular belief.But in this picture of scarcity, what is real, and how much of it is constructed?

New research around the discrimination against people who are homeless answers this, at least in part. When we speak of homelessness, we speak of poverty, inequality, violence, and crime. People without shelter are most likely to be falsely linked to a lawlessness, and “antisocial behaviors” that put the social order and safety of a neighborhood at risk. But criminologists in the U.K. looked at the link between reducing homelessness and crime in 10 towns. “Rough sleepers” — people who sleep in places not designed for living, representing the most visible form of homelessness — were wrongly criminalized by surrounding neighborhoods. Moreover, dispersing them or removing them from the streets in the pursuit of reducing antisocial behaviors didn’t really make a difference.

The social construction of homelessness thus casts people as “social deviants,” and also implies that the removal of these individuals from our streets is the only way to catalyze security and prosperity in neighborhoods.

Falsehoods, both.

Homelessness reflects a failure of society in granting people the right to housing and is a form of structural violence against marginalized communities. Tying homelessness to individual criminality and anti-social behaviors ends up obfuscating the role and responsibility a welfare state is meant to play; moreover, the myth also acts as a tool to keep the status quo intact, with there being no impetus to change it. Homelessness is a result of structural violence, not a cause of crime and poverty. Yet, the state continues to view them as “encroachers” or perpetrators of crime, rather than people with a right to safe housing. “The actual motivations for state action in the housing sector have more to do with maintaining the political and economic order than with solving the housing crisis,” as researchers noted in a 2016 paper.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the Design of Our Cities Reflects Caste, Class Anxieties

And, criminalizing people who are homeless reveals a murkier truth in that they are more likely to come in contact with the criminal justice system, and thus more likely to be incarcerated too. In debunking both these notions, the idea of home becomes central, even political.

There is an overwhelming body of research to show people without sheltered homes are seen as incompetent, violent, and the “lowest of the law.” “This elicits the worst kind of prejudice – disgust and contempt – and can make people functionally equivalent to objects,” noted a paper, which “further enhances the perceived legitimacy of negative treatment against the homeless and, in turn, further compromises an individual’s ability to cope with discrimination.” The prevalence of people sleeping on the streets provokes deeper questions about who has a right to claim space in a city.

The link between homelessness and criminality thus attaches itself to the pervasive belief that camps or sites where homeless people live generate crime. Think of slums, refugee camps, or resettlement colonies, where mostly people from marginalized castes, classes, and ethnicities find shelter. These are most likely to be present in lower-income neighborhoods and the perception is that these are areas where crime thrives. This feeds into misplaced ideas, where the perception is that slum-dwellers or those without permanent homes are involved in the majority of crimes — creating a perception of threat where there is none.

“It’s very difficult to say that the encampments themselves are what’s creating the crime,” Alexis Piquero, a sociologist at the University of Miami who studies policing and homelessness, told NPR. “What that means is that the area around those encampments is already criminogenic — it has the ingredients, if you will.”

This link also runs as a feedback loop. A home gives people economic and social mobility, both of which are denied to marginalized groups, making them more likely to come in contact with the criminal justice system. “Without investments in evidence-based solutions, communities often use police to respond to people living outside, criminalizing homelessness and issuing citations and arrests for minor ‘public nuisance’ crimes—such as camping, loitering, and public urination—that people wouldn’t have to endure if they had a place to call home,” a report noted. Moreover, research shows laws that criminalize homelessness make the problem worse, by virtue of being unfair, exploitative, and dehumanizing in nature. In the early 2000s, local authorities in Hungary ran an anti-homeless campaign where they amended local ordinances to ban people from begging, sleeping in public places, and picking up left-over food — because city areas must be protected and social order preserved. This is a trend already true for Dalits, SCs, STs, Muslim people in India; most convicts and undertrials in India are from the Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, OBC, and minoritized backgrounds. This isn’t for a higher prevalence of crime in these communities over others — rather, it’s the social construct of criminality associated with them that makes them easy targets, leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy

Related on The Swaddle:

What Happens to Right to Housing When We Call People ‘Encroachers’

These run-ins with the criminal justice system by virtue of homelessness increase people’s chances of incarceration too. Interestingly, up to 15% of incarcerated people experienced homelessness one year before their admission to a prison, according to a 2018 survey. The criminalization of people without homes further traps them in a “homelessness-jail cycle.” Research shows that a large portion of people released from jails returns to homelessness, because of barriers to employment, healthcare, and housing welfare support systems. This only speaks to the problem with the punitive justice system that punishes the person for structural inadequacies; “law and order” become tools of oppression by people in power.

The links with criminalization are also bolstered by discrimination against people, who carry a sort of “social deviance” to them and aren’t perceived as “fully human” in the first place. There are sobering estimates around the prevalence of mental illness among people who are homeless, but this link works to further the stigma around their personhood. Homelessness, incarceration, and mental illnesses are interlinked, but this is a link that is formedbecause of people’s limited access to healthcare and support systems. By not having health insurance, they do not get treatment for mental illnesses, substance abuse, and other health conditions.

“And it’s getting worse – the more visible people sleeping on the street become, the more negative is the response from authorities, the stereotypes perpetuated by the media and the indifference of the general public,” wrote Renata De Souza, Researcher/Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights at Amnesty International. In 2017, a Mumbai tribunal body blamed a victim who was killed by a motorcycle, because he was “negligent” for sleeping on the road. “He should have at least slept on the footpath,” the body said, reflecting the callousness of a system that rushes to prescribe equality on people living unequal lives.

It creates a vicious cycle where people can never really leave the streets, but can’t live there too. To go back to Walby’s dilemma, the crisis of home is one that is constructed ruthlessly. Can we ever fathom a solution? In Finland, homelessness appears to be falling, as officials decided to make housing unconditional to everyone.

Juha Kaakinen, who helped build the country’s affordable housing policy, said: “To say, look, you don’t need to solve your problems before you get a home. Instead, a home should be the secure foundation that makes it easier to solve your problems,”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

How Bisexual Erasure Undermines What It Means to Be Queer