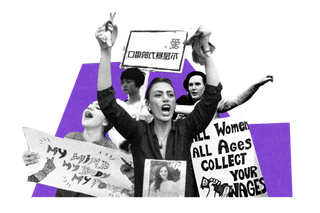

What Makes Women‑Led Protests Different From Others?

While mass uprisings are generally associated with reclaiming democratic values, women’s protests have to do with reclaiming the body.

The ethnographer Saidiya Hartman in her essay Venus in Two Acts talks about what it means when we know of marginalized experiences — in this case, two enslaved girls making the trans-Atlantic journey and dying en route — only through the documentation of the oppressors. “[T]he stories that exist are not about them, but rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives, trans-formed them into commodities and corpses… The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property, a medical treatise on gonorrhea, a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.”

This is the narrative of many women who, in the course of history, in the name of culture, and in furtherance of society, have been indelibly marked — either through death, assault, violence, or erasure. It’s what happened to Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman from Iran, who is said to have died in police custody for improperly wearing a hijab. Her life’s end would have been recorded in the state’s words, wherein future historians would have known her as nothing but a person recorded in police archives.

But Iranian women chose to prevent this from happening — over the past few weeks, they broke out into fierce protests against the authoritarian dictatorship that killed a young woman for, literally, having a hair out of place. And in doing so, they began to rewrite Amini’s story.

The ongoing protests in Iran speak to a more powerful impulse behind women-led protests worldwide. When women rise up as a force, it is often with a specific intent that sets these protests apart from others: reclaiming not only space, but the body itself. In claiming ownership of their own bodies — as a collective — women’s protests blur the arbitrarily imposed line between the public and the private. More specifically, the public, as a site of politics, and the private, as a site of domesticity. By resisting what happens to women’s bodies in private, women-led protests show that there’s no such thing as the public-private divide — it’s public policies that operate in the private, both colluding to confine women to a sphere of silence and compliance.

Related on The Swaddle:

A Brief History of Indian Women Protesting Gender Inequality

Take this statement by the organizers of #NiUnaMenos (“not one woman less”), a series of protests against femicide that erupted across Latin America: “We are declaring that we do not renounce sovereignty over our bodies-territories and therefore, we do not recognize their power to represent us and legislate over and against us…We want ourselves alive, free, without debt, and desiring.” They emphatically proclaimed “the rapist is you” — pointing to the president, the military, and the state itself, as figurative rapists.

Argentinian anthropologist Rita Segato calls this the “masculine mandate” which creates the public-private binary — one that, through public consensus, enacts violence against women in private.

It’s when women begin to recognize this and speak, that the state visibly shows its anxiety. In China, feminists protested domestic violence through their “bloody brides” demonstration in 2012. Over time, this grew into resistance against a larger culture of sexual harassment — one that led to the detention of five women, known as China’s “feminist five”, charged with “subverting state power.” The writing on the wall is clear: drawing attention to the ways that patriarchy violates women in private, subverts the state’s interest in relegating these issues as “not public,” and keeping the subjugation intact.

Pakistan’s Aurat Marches — especially in the wake of Qandeel Baloch’s murder — touched upon similar ideas. What does it mean for a community’s honor to be confined in the body of a person? Can a woman retain a sense of personhood when representing a community’s purity? The consequences of resisting an imposed honor were devastating, showing how when women claim their bodies in real life, they’re forcibly separated from them through murder. Baloch’s murderer was acquitted, leading to this year’s Aurat March Lahore theme being “Reimagining Justice” that demands nothing short of a complete overhaul of existing institutions.

In Turkey, women took to the streets earlier this year to protest President Erdogan’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, which was designed to legislate and prevent gender-based violence — especially domestic violence. Two years earlier, a “wall of shoes” in Istanbul represented the consequences of gender-based violence: showing, visually, an absence of bodies to fill the shoes. The absence is by design — these are disappeared bodies, the shoes representing an emptiness where there should have been life.

Related on The Swaddle:

In Shaheen Bagh, Muslim Women Redefine Carework as Resistance

Then, an Indian woman’s death in Ireland, after being refused life-saving medical care due to strict abortion laws, once again turned into a watershed moment, one that eventually led to the overturning of the law itself. Soon after, what was once a right was overturned in America, creating a cyclical pattern of bodily violence across the world.

Even way back in 1972, Italy’s ‘Wages For Housework’ campaign stressed the injustices waged in private — as women’s bodies were put to work under an arbitrary notion of care, replenishing individuals in the home while themselves being depleted, in the process. One of the campaign’s founders, Silvia Federici, noted that “its power resided in the fact that it gave us great comprehension of society and the mechanisms of exploitation, and at the same time it touched the most personal aspects of our lives, while enabling us to connect to all other women with a new sense of solidarity.” In other words, it disturbed the public-private binary — and through acts of protest embodied in song, slogans, writing, and joy expressed in public, indicted capitalist patriarchy for perpetuating it.

Indigenous women represent the infinite loop of violence that the masculine mandate subjects them to. Amid revelations of mass graves of indigenous children in Canadian school sites, women rose up in protest against the institutional violence that, to date, continues to kill and disappear indigenous women.

“What we’re living through now isn’t any different from what we’ve always faced when it comes to this extermination effort. We’ve seen centuries of violence, spilled blood, rape and enslavement – and now all of this is being officially professed by the government,” said one indigenous woman who protested Brazil’s destruction of forest lands — pointing to a much more primordial struggle. Indigenous populations are feminized populations — regarded as dispensable, outside public considerations of “development.” Their connect with nature is key — when nature is seen as a resource to be invaded, occupied, plundered, and settled on, it assumes the form of a feminized entity.

The devaluation, violence, and degradation that women resist in protests, then, is as old as time — and is a global pattern of subordination that takes different forms. At every turn in women’s protests is the body as a political site — one that’s never been considered a political entity by the state. Whether it be cis, trans, Muslim, Hindu, indigenous, or poor women, bodies emerge as a frontier for oppression and liberation, both. It’s a quiet rage that’s been burning, centuries in the making. Whether it’s for the right to wear a hijab or the right not to wear one, the struggle remains one predicated upon what society does to women while relegating their concerns, bodies, and entire existence to the “private.” And in Iran, the rage manifested in a singular act of bodily defiance: a woman, sitting on a platform before a crowd, chopping off her hair in an instant — daring anyone to stop her.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Union Tourism Ministry Announces an ‘Ambedkar Circuit Train’