‘Quality Boredom’ Can Be a Way to Reclaim Our Time

There is a right way to be bored, and when processed meaningfully, boredom offers a way to make amends with who we are and what we do.

Over 2,000 years ago, somewhere in Rome, stoic philosopher Seneca documented a crisis of the mind: “How long the same things? Surely I will yawn, I will sleep, I will eat, I will be thirsty, I will be cold, I will be hot. Is there no end?” Seneca was bored. He was probably feeling the “noonday demon” — what the Middle Ages monks termed lethargy and agitation that comes with the repetition of daily lives.

Boredom is incredibly fascinating to think about. What is the point to it? Of restlessly walking around, anxiously turning in bed, fretting at a loss of things to do. Restlessness, anxiety, and fret all point to a sense of unease that comes with being bored — by pointing to the fact how unequipped we are to having our time be our own. Is there a point to boredom? Sometimes. It requires distinguishing between boredom as a state which we dip into every now and then, and boredom as a personality trait that signals a more chronic dissatisfaction.

But boredom doesn’t have to be our undoing. The land of torpor presents a chance for meaningful reflection, social connection, and sparking a creative energydried and dull, something affirmed in studies done over the years. There is a right way to be bored, and when processed meaningfully, boredom offers a way to make amends with who we are and what we do.

Is boredom an emotion? Partly yes, for it signals a lack of satisfaction and can motivate people to do something about it, just the way “thirst” and “hunger” do. It is also an ongoing cognitive process, wrote psychologists James Danckert and John D. Eastwood In Out of My Skull. They define boredom as the uncomfortable feeling of “wanting to do something, but not wanting to do anything.” We’re bored, feeling an indescribable restlessness and waiting for the world to get better. But we’re also not: we’re constantly falling into digital bubbles and picking up tasks and keeping ourselves occupied because we can’t imagine a reality where our time is not fragmented into pockets of productivity.

“Quality boredom” is a more refined way to understand what possible benefits boredom can have for us. For one, a bored person is more likely to be creative and productive, even if that sounds unintuitive. Studies dating as far back as the 1970s point out this link; this was again reiterated in 2019 when a study found people who were asked to do methodically boring tasks, let’s say one of sorting a bowl of beans by color, ended up with better ideas than people who first did a more “creative activity.” The 21st century has a host of such research squeezed within: this 2014 study asked people to find different uses possible for a pair of plastic cups, and another asked people to do a seemingly mundane task too. In all cases, those who were bored more, ended up with a more prominent creative flair.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Being More Self‑Compassionate Can Help Us Feel Less Bored

This makes sense: when the mind is bored it wanders and even daydreams, the mental recesses can indeed spark creativity, generate ideas, or conjure up interesting ways to solve situations. It’s hard to be ever truly bored given we’re absorbed by our digital worlds, but the research makes a strong case for creating ideas if we can’t find them.

While boredom may represent an inertia, it has the potential to inspire people to action. The restlessness that comes with the desire to do something can motivate people in ways more than one. “The negative and aversive experience of boredom acts as a force that motivates us to pursue a goal that appears to us to be more stimulating, interesting, challenging, or fulfilling than the goal that we currently pursue,” argued philosopher Andreas Epidorou in a 2014 Frontiers in Psychology article. This is something evolutionary psychology shows too: being stale and stodgy could have helped push people to find new ways of growing. “A dull village life might have prompted our ancestors to explore what might be across that river, or perhaps to try a new berry they found in the woods,” wrote Sara Chodosh in PopSci, calling this an “evolutionary quirk.”

Can we ever truly tap into boredom though? According to Sandi Mann, a senior psychology lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire in the U.K, simply letting the mind wander, without any stimulation to guide it, is one way. Quality boredom demands deliberately picking an activity that doesn’t require the brain to churn. Think walking a familiar route, sitting with eyes closed, even swimming laps. Scrolling through feeds doesn’t count here because it does require concentration and mental labor to a degree.

Instead, the idea is to plunge into activities without looking for a clear reward — it’s almost as if we’re tricking our brain into not seeking anything. There’s research to show why people feel inspired or more creative after spending some time in nature. “If you’ve been using your brain to multitask—as most of us do most of the day—and then you set that aside and go on a walk, without all of the gadgets, you’ve let the prefrontal cortex recover,” said the researcher of a 2012 study. “And that’s when we see these bursts in creativity, problem-solving, and feelings of well-being.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Has the Pandemic Made Us Less Interesting Than We Used to Be?

During the pandemic, we also understood how destructive boredom can be. It became shorthand for any experience that made us feel disconnected from our realities, so much so that the lockdown blurred the lines between boredom and depression as a whole. This naturally has worrying implications, for it exaggerates our general uneasiness with a malaise so deep that it sets within our bones. But this is not a problem that goes by looking away; we can’t turn away from the tedium in and around boredom.

We are accustomed to not having time to be bored or think. A 2014 study found that many people chose to administer painful electric shocks to themselves, rather than being left alone with their thoughts, noted The Guardian. One man shocked himself 190 times in 15 minutes. Our unease with boredom remains rather adversarial, to say the least.

The problem runs much deeper: there is a cultural misunderstanding around the idea of boredom. People who are bored are quickly cast as “lazy,” “uninspired,” not curious. We measure individual worth with productivity, productivity with physical action, and action with results. There’s a hint of mechanical predictability at play, one that takes the vintage of efficiency. But boredom promises nothing; free time or downtime is thought to be time wasted. It is also subversive and anxiety-inducing for the status quo, for people who have the capacity for boredom are also people who can think and radically imagine realities outside capitalistic norms of productivity.

There is no better time to understand boredom better, and even embrace it. For one, it is very important that we understand how boredom isn’t a static state; it involves action, ideological and physical, some more evident than others. Two, there’s a hint of self-reflection at play here. If we are not doing anything, we have greater time and energy to take stock of desires, choices, and relationships.

This is a plea for giving the brain time to wander, and for letting us claim time as our own.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

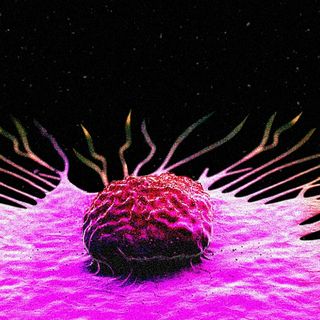

Breast Cancer Spreads More Aggressively at Night, Finds New Study