Rupi Kaur’s Moral Clarity Has Been Consistent. Does it Change How We View Her Artistry?

The role of artists in times of humanitarian and political crises cements their legacy – and changes our retrospective interpretation of their work.

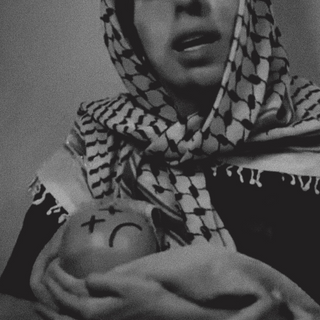

Rupi Kaur, the infamous Desi Canadian poet, is once again the epicenter of online discourse – but this time in her favor. Kaur took to social media to share her decision to decline an invitation from the White House to attend a Diwali celebration hosted by Vice President Kamala Harris. “ I’m surprised this administration finds it acceptable to celebrate Diwali when their support of the current atrocities against Palestinians represent the exact opposite of what this holiday means to many of us… I refuse any invitation from an institution that supports the collective punishment of a trapped civilian population,” Kaur noted in a statement condemning the administration’s stance on Israel’s ongoing siege of Gaza. It prompted many to reconsider their opinion of her, and thereby – her legacy.So far, the idea of separating the art from the artist has applied to situations where previously beloved artists are disgraced. Here is a situation, however, in which a widely mocked artist is re-evaluated in light of a progressive position. Is Rupi Kaur’s poetry retrospectively better than we thought it was, or does the art remain unchanged?

Despite weathering continuous derision, with critics proclaiming her as the harbinger of poetry's demise – Kaur was named “Writer of the Decade” by The New Republic. Titled the “Queen of Instapoets” her journey has been marred by accusations that she strategically propelled her career through a "faux controversy."

“The self-appointed spokesperson of South Asian womanhood is a privileged young woman from the West who unproblematically claims the experience of the colonized subject as her own, and profits from her invocation of generational trauma” is how a piece on Buzzfeed analyzed Rupi Kaur’s poetry and persona. Remarking on Kaur’s instantaneous fame the author called it “a tale of sudden virality and savvy capitalization”. The piece also noted how Kaur’s narratives do not originate in “authentic South Asian experiences” and that her “social media strategy” is of “perceived universality” which reduces the “collective trauma’’ of the colonized people into bite-sized nuggets of “foreignness” making it palatable for her White audiences.

However, Rupi Kaur, a New York Times bestselling author, besides being in the news for her oft-questionable poetry skills, has always been on ‘the right side of history’ – particularly on issues involving the persecution, colonization and disenfranchisement of colonized, marginalized people, as the Internet is now noticing. Former skeptics turned to introspection and are now flooding social media with posts expressing apologies, acknowledgements, and applause for Kaur. One X user, replying to Kaur’s post, wrote, “proof that corniness and moral clarity are not mutually exclusive.”

This newfound respect and recognition of Kaur's public persona raises questions about the evolving relationship between artists, their work, and societal expectations. Here’s how one X user put it: “I'd talked sh*t on your name, but you standing up like this means way more than whatever feelings I had about your work,” showing how the current moment prompts a reevaluation of the artist's impact beyond their artistic expressions. The flurry of numerous such posts celebrating Rupi Kaur takes us to a critical point in the conversation— the intersection of art, the artist, and their politics.

One of the main critiques of her poetry is its diffuse politics, ultimately milquetoast and universally applicable. This, despite Rupi Kaur explicitly staking a political claim over her poetry, dealing with themes of diaspora, immigration, trauma, and identity. But this has, unlike with several artists today, translated directly into her views on world events too – especially those pertaining to the very subjects she writes about, giving them a tangible, specific context. When the Indian Parliament revoked Jammu and Kashmir's special autonomy written into Article 370 of the Constitution, and when it passed the Citizenship Amendment Act and endorsed the NRC which threatened to make already alienated sections of the population stateless, Kaur openly opposed them and, moreover, supported the Shaheen Bagh protests. “Attacks on minorities have been a constant legacy of the Indian state. Whether on Dalits. Sikhs. Christians. Muslims. Women. and countless more. The human rights abuses we are seeing now are routine for the state. Coming from the Sikh community who knows intimately the terrors that are unleashed when the media is either absent or complicit with the actions of the government,” she noted in a Facebook post in 2020. Later in 2021, at the height of the Farmers Protest in the national capital of Delhi, she urged her audiences to speak up in support of the farmers and wrote, “when each of these [oppressed] communities tried telling the world their lived reality over the past decades- they were labeled as extremists or terrorist. Now social media is helping people see the truth. India hides behind the cloak of democracy to get away with its crimes. Farmers need us now more than ever to refocus on the bills. The bills are an attack on the livelihood of farmers.”

It wasn’t until her latest on Gaza that Kaur’s image began to be viewed differently: “As a community, we cannot remain silent or agreeable just to get a seat at the table. It comes at too high a cost to human life. Many of my contemporaries have told me in private that what's happening in Gaza is awful, but they aren't going to risk their livelihood or ‘a chance at creating change from the inside.’ There is no magical change that will happen from being on the inside. We must be brave. We must not be tokenized by their photo-ops. The privilege we lose from speaking up is nothing compared to what Palestinians lose each day because this administration rejects a ceasefire”.

It prompted one question: does her overt political outspokenness add weight – and renewed value – to her poetry?

For many, it doesn’t. This is the "art for art's sake" argument: a slogan with its origins in the rebellion of Artists that translated into the Aestheticism movement of the late 19th Century, championed by the likes of Oscar Wilde and Victor Hugo. The philosophical enterprise stood to denounce the accustomed role of art from that era – aiming to liberate art from its traditional roles of serving the state, religion, or adhering to Victorian moralism, and championed artistic freedom and expression in movements like Impressionism and modern art.

The belief that an artist should primarily serve as a vessel for self-expression in the guiding philosophy of ‘art for the sake of art’ affirmed that art was valuable as art in itself; that artistic pursuits were their own justification; and that art did not need moral justification, and indeed, was allowed to be morally neutral or subversive. Yet when philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche argued that there can be 'no art for art's sake', and proclaimed, “Art is the great stimulus to life: how could one understand it as purposeless, as aimless, as l'art pour l'art [French for ‘art for art’s sake’]?” Eventually the movement fell out of favor amidst calls for the politicization of art. This suggests a fundamental inquiry about the purpose of art — is it solely aesthetic, or does it inherently carry a broader social and political significance?

Art for Art's Sake was a call to reject the artistic traditions which favored the moralizing standards of the status quo; It was a resistant movement that withdrew from imposed political and ideological matters, retaining radical intent even as it distanced itself from explicit political engagement. Yet, whenever the phrase is revisited in modern times, its true origins are often consigned to oblivion. In contemporary interpretations, it transforms not merely into a defense of artistic autonomy, but into a protective shield that liberates art from the weight of ethical scrutiny. This shield served to divorce art from the burden of being ethically judged based on the creator's engagement or lack thereof, from public matters; absolving it from the responsibility of serving a specific purpose beyond its intrinsic artistic merit.

On the other hand, there is a case to be made for the fact that artists’ real lives do inevitably influence interpretation of their art irrevocably. George Orwell’s socialist politics in real life inform interpretations of his novels; Sylvia Plath’s and Virginia Woolf’s melancholy inform how we view their poetry and novels; Frida Kahlo’s works are often seen as autobiographical, reflecting her physical and emotional pain; while Bob Dylan’s personal and political experiences, including his involvement in the civil rights movement, is known to have influenced his songwriting.This perspective prompts a consideration of whether art, in its creation and reception, is inseparable from the lived experiences and ideologies of the artist.

Then, there’s the question of identity which has come to define artistic interpretation. “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best,” remarked Frida Kahlo, answering why her creative work centers her life experience as a running theme. Rupi Kaur also asserts her identity strongly in her work and outside of it. Still, criticism around Kaur has been dismissive of her background and political identity she upholds – that of a Sikh-Punjabi woman, unlike the fail-safe moniker of South Asian or Indian.

There aren’t clear answers as to how history will remember her art, though her consistent moral stances do put her down as an artist on the right side of history. In being unabashedly political in her real life, then, Rupi Kaur fares far better than several other artists who make political claims in their art, but remain silent during a crisis. At the very least, it does prompt a re-evaluation, if not reclamation, of her poetry: on being asked during a Harpers Bazaar interview whether poetry has always been political for her, she said, “My Dad was an activist and I grew up in a house where conversations about human rights were always at the center of our discussions. Life has always been political and that means the personal is too. It is our responsibility to tackle issues of women’s and human rights and I am very comfortable in that space. Not everybody feels comfortable to talk about these things, but I will continue to discuss them for the rest of my life”.

In doing so, Rupi Kaur shows how artists possess the agency to contribute to a shared narrative — a power particularly pronounced in times demanding collective reflection. And within the crucible of public discourse, when artists transcend their conventional role as mere creators, their part in history-making remains not a mere footnote but a reckoning legacy, urging our retrospective interpretation of their artistic oeuvre. It’s clear in the way scores of social media users are purchasing Kaur’s work in support, with one poet and X user commenting: “The resurrection of Rupi Kaur is upon us."

Naina is a sociology graduate of the Delhi School of Economics. She presently works as a writer focusing on queer theory, culture, media semantics, and women's health.

Related

Is Taylor Swift Impossible to Critique?