Saving Dharavi Through Rap

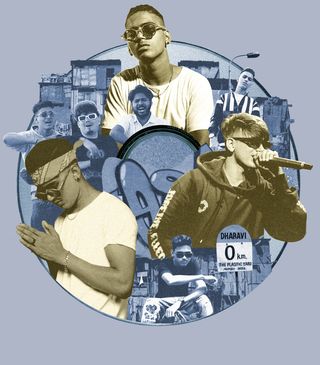

How Noor Hasan and Rekoil Chafe redefine what development means for Dharavi.

Change is said to be the only constant. But inside Mumbai’s Dharavi slum, everything appears to be static. “It’s been nearly 19 years since my family moved into this slum,” says rapper Noor Hasan. “But Dharavi waise ka waise hi hain.”

Noor has been a Dharavi boy for as long as he can remember. In his own life though, from when he first arrived there as a toddler, he has witnessed many changes. Today, he raps about growing up in the gullies of the slum and has earned fame, fans, and enough money to buy himself a few-odd luxuries. But what the 23-year-old really wants is a decent home for his family. “We only hear snatches about how this and that is going to happen in our neighborhood.”

But that “badlaav” the residents have been hopelessly waiting for seems like a mirage – it only looks real from afar.

For the likes of Noor, who’ve dared to push the boundaries with their art, where they happen to live has come in the way of their dreams once too often.

One of the largest and densest informal settlements in the world, with an estimated population of nearly one million packed into 2.6 square km of land, Dharavi has long been used as a playground for successive ruling governments, whose legacy includes a roster of unfulfilled development promises.

The newest in line is billionaire Gautam Adani-led Adani Realty, which won the bid to redevelop the neighborhood. But the project, which is part of a joint venture with the Maharashtra government, has ruffled feathers within the community.

The international bid put out by the state government states that nearly seven lakh people are likely to be displaced due to the project. Vinod Shetty, a labor lawyer and founder of Acorn Foundation, who advocates for waste pickers in Dharavi, says “With more than half of the population facing the risk of displacement, there is definitely anxiety among the residents.”

This unrest is what inspired Noor’s most recent rap, “Dharavi ka Dada Kaun.” The song – made in collaboration with Lil White aka Yogesh Devara (another Dharavi rapper) and Rekoil Chafe (aka Shubham Chafe) – gives voice to the anguish of the residents: “Who sets our price? The rich savor pleasures, while the rest suffer… We’ve always heard how Dharavi will develop, but we’ve got nothing, things have become worse; Water, power, gas... all a distant dream; Governments do no work,” the rap opens in Hindi, “Who does Dharavi belong to? Who is the dada here?”

The rap has allowed Noor to give vent to his feelings about the redevelopment project, which he fears has ignored the ground realities of his neighborhood.

Noor, who entered Dharavi’s indie music scene at the age of 17, was raised in Chamdaa Bazaar in Dharavi and went to a local municipal school. His father hails from a village near the Nepal border, while his mother is from Bihar. “Even as a child, I was thinking big. I would hang-out with the adults and dream about doing something different. I tried my hands at everything possible, and even took part in a reality television show [Dil Hai Hindustani].”

He found his idols in the famous rappers Divine (Vivian Wilson da Silva Fernandes) and Naezy (Naved Shaikh), whose 2015 rap song “Mere Gully Mein” brought a lot of attention to the underground rap scene in Mumbai. “Divine had come for an event in Dharavi’s Shahu Nagar to promote the song. After that I would shadow him and Neazy everywhere and learn to rap like them,” he recalls. Divine took a shine to Noor and even helped arrange for a studio to record his debut song. Noor sold his phone to pay for a videographer to shoot and edit the video for it.

In the track, “Kal Ka Superstar” (“Tomorrow’s Superstar”), Noor proudly flaunts his identity as a boy from “Dharavi 17” – a reference to the pincode of the area. He takes a dig at the rich and speaks about wanting to rid the country of poverty. It won him instant fame. “My ammi wasn’t convinced about the path I had chosen for myself. She felt I was wasting my time and would discourage me often,” says Noor. But after that rap became viral, and Noor became popular among the kids in the neighborhood, he says his mother was the most proud. “I even bought her a phone,” he smiles.

All of Noor’s writing is heavily autobiographical. In one of his most recent hits, “Mera Safar” (“My Journey”), he raps about starting from scratch in the slum, being at the receiving end of hate and eventually becoming a face that people recognized. “Na main hu gareeb, nahi paiso ki lalach hain… khaata bhi khilata bhi, aisi apni aadat hain (Neither am I poor, nor am I greedy… I feed myself and everyone, because that’s who I am),” he sings. “This is one of my personal favorites,” he says. “It gives people a window into what it takes to start from where I did, and how I fought all odds to become a rapper.”

It upsets him when people attach stereotypes to his neighborhood. “People say a lot of wrong things about this place. They call our boys ‘awara’ and good-for-nothing.”

Noor counters these unpopular narratives by highlighting the “truth of his existence” and that of his people. “Main hawe main baat nahin karta (I don’t make up things).”

Dharavi’s rappers have always put the neighborhood at the center of their work. The music culture has bolstered a generation of youngsters to speak up without fear or reservation. Their no-holds-barred writing rarely distinguishes between the personal, political and social. “These artists talk about their lives, their frustration, the police, the harassment, exploitation and the discrimination they’ve faced, all because they come from Dharavi,” explains Vinod, who also founded Dharavi Rocks in 2008, an organization that imparts music education to children from the neighborhood. “A lot of [the music] is a cry of anguish and about demanding respect from society.”

“Dharavi ka Dada Kaun” was co-produced by veteran journalist and author Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, who realized that rap was a powerful tool to capture what was happening in Dharavi. “The idea that music is just for entertainment is inaccurate. That songs, or the depiction of songs through an audio-visual medium, could carry social, political messages is something that I firmly believe in,” he says. Artiste manager Ojas Shetty says the rappers even went on ground, attending one of the early protests by residents opposing the project. This ethnographic approach fuelled their lyrics. The music video is part of a larger project comprising a range of video interviews and articles, to be unveiled soon on a website, to create awareness about issues related to the development project.

Vinod says the project, at least in its present form, doesn’t account for the rehabilitation of migrant workers, many of whom are daily wage earners. According to Paranjoy, there are about one lakh migrants in the neighborhood. “Dharavi is not just a place where people live. There are tens of thousands of small and micro enterprises, where people make a wide variety of products and offer their services. They make idlis and dosas, leather articles, do zari work and recycle plastics.”

Most of these migrants cook and sleep inside these factories and karkhanas, or pay paltry rent and live cheek by jowl under inhuman conditions inside small rooms. “They subsidize their living by not traveling and finding accommodation outside Dharavi,” says Vinod. But many of these factories are going to be declared polluting and hazardous and are unlikely to be given license to continue within the Dharavi Redevelopment Plan. “So, migrant laborers working in industries like recycling will get pushed out. They will have nowhere to go.”

A situation like this needs to be treated with empathy, Vinod feels. An empathy and understanding that only those within – like Noor – can bring. The government is currently not even talking about the unemployment and displacement that the redevelopment project could create. “Which is why there’s a huge disruption facing Dharavi today.”

With an extremely mixed community, hailing from all over India and cutting across religious and caste divide, Dharavi remains an embodiment of the country’s pluralistic values. It’s a microcosm of a truly secular society. A threat to the neighborhood’s diverse fabric, even in the name of redevelopment, could have far-reaching implications.

Kalyan-based rapper Rekoil Chafe resonated with these concerns. “I’ve always wanted to highlight the dynamics of the oppressor and oppressed in my work,” he says, explaining why he decided to collaborate with Noor and Lil White on Dharavi ka Dada Kaun. “We have family and friends who live there, and I know what they are experiencing,” he says.

Growing up, Rekoil was fed on a diet of music that harked back to the teachings and struggles of Babasaheb Ambedkar. “My father played a lot of this music at home,” says Rekoil, who was raised in Vikhroli. “That music subconsciously informed my thoughts.” Rekoil started as a video editor and gamer but his curiosity for rap led him to try and write his own lyrics when he was 15. “This was in 2010,” he says. At the time, the rap culture was just about picking up. But it was only in 2016, when his group, The Hip Hop Movement, started organizing rap performances in malls that he started taking it seriously.

Over time, Rekoil has also come to realize the potential of his work. “Rap is an art form based on protest,” says Rekoil of the genre of music, which has its origins in the hip hop culture that emerged in the 1970s in the boroughs of Bronx, New York City, and became a form of expression for poor African-American, Caribbean, and Latino immigrants living in the United States. “You can’t disengage protest from rap… it has always been about those living on the streets and their reality. It mirrors what happens in society.”

His Ambedkarite background has played a significant role in shaping his understanding of the world and the problems that affect the marginalized. “Living in the city, one doesn’t realize how discrimination plays out,” he says. This one time, he remembers being denied tea in a porcelain cup. “The tea boy was asked to serve it to me in a Styrofoam cup, when everyone else in the room was having it in regular cups. It made me question a lot of things, especially why this incident had happened to me, and how I could deal with such a situation if and when it presented itself in the future again.”

Rekoil pored over literature that explored issues around class and caste, and that became his material. He writes and raps in English, Hindi as well as Marathi. One of his Marathi rap songs, “Dolyat Swapna, Dhagaat Paay (Eyes Filled with Dreams, Legs in the Clouds),” talks about the need to prioritize self-respect when belonging to the lowest strata of the society. He writes: “Baba mhane ‘sangarsh kayam rahil’; Kaka mhane ‘zidd hi sodavi nahi’; Paathi la nahi jhadu, galyat nahi madka thuken majhe bol, chaap thevin paayi (Baba told me ‘the struggle will go on’; uncle told me ‘yet keep your will strong’; No broom on my back, no pots on my neck, I’ll spit out my words, leave an imprint behind).”

The 29-year-old, however, doesn’t believe in being pigeonholed as a Dalit rapper. “I am not trying to stray away from my identity, but when you’re boxed, you are inadvertently separated from the mainstream,” he says. “Where I come from should not matter, my art should.”

After “Dharavi ka Dada” released in January this year, Noor and Rekoil received praise as well as brickbats from people who felt they were putting obstacles in the way of development. But Noor clarifies that they are not “anti-development.” “Like everyone else, I want Dharavi to be redeveloped,” says Noor. “But I also want each and every person living here to get what is rightfully theirs. They deserve their share, and we all deserve a new life.”

Jane Borges is a senior journalist, author and memory keeper. Her debut novel, Bombay Balchão (2019), was shortlisted for the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puruskar and Atta Galatta Bangalore Literature Festival Book Prize. She has also co-authored the non-fiction Mafia Queens of Mumbai: Stories of Women from the Ganglands (2011) with S. Hussain Zaidi. A chapter from the book was adapted into the Bollywood film Gangubai (2022) by Sanjay Leela Bhansali. She is the co-founder of Soboicar, an oral history archive chronicling the lives of Catholics who migrated from the Konkan to South Mumbai.