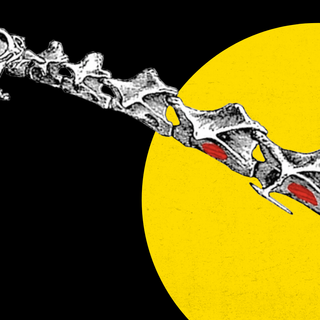

“Tens of thousands of elephants are being killed every year for their ivory tusks,” the World Wide Fund for Nature stated. However, scientists may have figured out a way to examine the the DNA of seized ivory tusks to expose the criminalnetworks involved in poaching, which can eventually help put an end to the illegal activity.

A team of researchers from the University of Washington in the U.S., worked with special agents with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, to test the viability of genetic testing to uncover the international networks that make ivory poaching rampant.

Poaching of elephants, in fact, is so high that ant elephants are evolving to be tuskless, according to a study published last year, which proves humans are “literally changing the anatomy” of wild animals. Perhaps, the DNA testing to expose criminal networks behind poaching will help preserve nature from human greed.

Published yesterday in Nature Human Behaviour, the study analyzed the results of DNA-testing performed on 4,320 tusks belonging to African savanna elephants. These tusks were obtained from 49 individual seizures of ivory made in 12 different countries over a span of 17 years — from 2002 to 2019.

Called “familial DNA matching,” this technique has been used by law enforcement in the past too. But interestingly, it wasn’t to expose poaching rings; but to nab a serial killer called the “Golden State Killer” who had evaded arrest for over four decades. For years, investigators looked for a direct match of his DNA found at the crime scenes so they could identify who was behind the crimes. When that failed, they decided to use the DNA they had gathered to look for biological relatives whose DNA may already be present in public databases. It worked.

Related on The Swaddle:

Madras HC Resolves Elephant Custody Dispute In Favor of Caretaker, Citing Their Emotional Bond

Here, too, the researchers have used a similar strategy. “If you’re trying to match one tusk to its pair, you have a low chance of a match. But identifying close relatives is going to be a much more common event, and can link more ivory seizures to the same smuggling networks,” explained lead author Samuel Wasser, a professor of biology and director of the Center for Environmental Forensic Science, who was also involved in developing the genetic tools for this exercise.

Their results suggested a high degree of organization within the networks than they had assumed. It appears that only a limited number of “big, transnational” criminal syndicates may be behind most of the poaching. — bringing down the number of networks law enforcement must dismantle.

“These methods are showing us that a handful of networks are behind a majority of smuggled ivory, and that the connections between these networks are deeper than even our previous research showed… Literally, we had dozens of shipments that were simply connected by multiple familial matches,” Wasser noted. In other words, the DNA of ivory tusks is helping to create a pattern of poaching syndicates.

“By linking individual seizures, we’re laying out whole smuggling networks that are trying to get these tusks off the continent… Identifying close relatives indicates that poachers are likely going back to the same populations repeatedly — year after year — and tusks are then acquired and smuggled out… on container ships by the same criminal network,” he added.

If employed, this would be a way to use already existing data to bolster the survival rates of elephants. At present, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN) the African savanna elephant, whose poaching the researchers investigated, is listed as “endangered” — largely attributable to poaching among other factors.