Scientists Are Using Mushroom Skin to Make Sustainable Electronics

Degradable mycelium skin, when used to create the base for electronic devices, can drastically reduce e-waste.

As mounds of e-waste continue to grow around the world, scientists are asking: How can technology get more sustainable? A team of researchers at Johannes Kepler University Linz believes mushrooms might hold the answer. They suggest that processed mushroom skin could be used to create the base for biodegradable electronic devices. These devices, dubbed “MycelioTronics” — after the part of the mushroom used for them — could be a first step toward replacing non-degradable and difficult-to-recycle materials, and potentially reduce at least a part of the e-waste we generate.

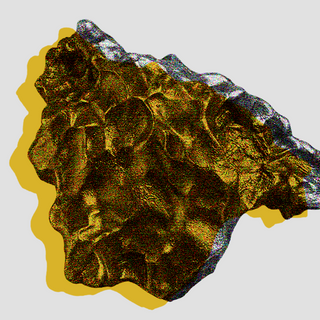

Specifically, the research was focused on Ganoderma lucidum, a type of mushroom that grows a glossy skin to cover its mycelium – a root-like structure from which the mushroom body grows – to protect itself from pathogens and other fungi. The researchers removed this skin and processed it further, soon realizing that the material, when dried, is flexible, robust and able to withstand high temperatures – properties that indicate the material’s applicability in creating the base, or substrate, that insulates and cools electronic circuits in devices.

Reports suggest mycelium has the potential to fuel the transition to a circular economy that moves away from the “take, make, waste” model of production and consumption. The team of researchers believe that using mycelium skin substrates in wearable and untethered electronic devices could drastically reduce the mounting piles of e-waste.

Their proof-of-concept study, published in the journal Science Advances, outlines how mycelium skin can be used to replace plastic polymers in crafting bases of printed circuit boards. These boards are made up of a range of components that are difficult to separate and recycle. In contrast, substrates crafted from mycelium skin decompose when exposed to light and moisture, allowing recyclable components to be easily separated.

The team deposited metal onto the mycelium skin using a process known as physical vapor deposition and laser ablation to create conductor pathways. When they tested this material, the results were nearly as good as using plastic substrates. They found the material could be bent repeatedly without suffering damage – it did not break even after 2,000 bends. They also used it to make some components of batteries.

“We have created proximity and humidity sensors, for example, and they also work well,” said Martin Kaltenbrunner, an electronic engineer at Johannes Kepler University Linz and an author of the study. The scientists did this by soldering electronic chips onto the mycelium substrate. They also demonstrated that the mycelium skin could be used to power wireless sensing devices, including a Bluetooth module.

Related on The Swaddle:

As most scientific discoveries go, this approach was “more or less an accidental discovery” too, said Kaltenbrunner. A slew of studies in recent years have catapulted mycelium into the limelight, heralding it as the ultimate sustainable building block for a green future. This versatile material can find use in a range of fields – from mycelium-based bricks in construction, to becoming a biodegradable alternative to leather, plastic packaging, styrofoam, and even being used to make plant-based meat.

To begin with, the researchers say this material could potentially be used in medical technology, where components need to work for up to a year. Other researchers have also experimented with natural materials in medical devices, such as implants which do not need to be surgically removed and can decompose safely inside the body. This is the relatively new field of “soft” or “transient” electronics, where components disintegrate after a certain period of time, facilitating the design of sustainable alternatives.

Previously, researchers have experimented with paper in electronic devices too. However, this proved to be too resource-intensive, the researchers noted in their paper.

The recent study also highlights how to process mycelium skin substrates. “It turns out you don’t need to do a lot of things to use it for electronics — you just need to dry it,” said Kaltenbrunner. “The mushroom skins only need waste wood to grow,” he added.

According to an article in Inverse, the researchers cultivated the fungus by growing Ganoderma lucidum on dead hardwood trees. They regulated the amount of light and carbon dioxide to prevent the fruit body from growing, as that would turn its skin rough. The mycelium skin was then harvested from young mushrooms.

Electronic waste is a burgeoning problem which poses several environmental and health risks. Earlier this year, it was estimated that 5.3 billion phones would be discarded in 2022. Despite the existence of e-waste recycling regulations across the world, devices that reach the end of their lifecycle often end up in landfills, leaching toxic chemicals into the soil. “It’s better to think about sustainable materials and approaches early on, because in the end, we’ll end up with a lot of waste,” Kaltenbrunner told Inverse.

The research is in its early stages, and there is a long way to go before mycelium skin can be instituted for industrial use in creating sustainable electronics. The researchers say one key area of future study must be how to ensure the cultivation process yields homogenous, smooth mycelium skin for consistent results.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

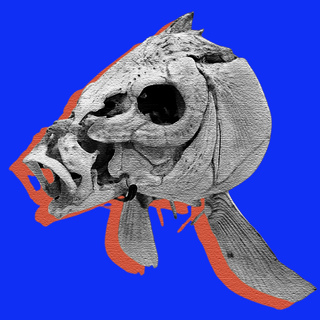

Archaeologists Discover the Oldest Evidence of Cooking in Pre‑History