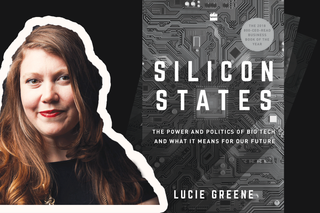

‘Silicon States’ Author Lucie Greene on the Gendered Dangers of Big Tech

“Siri, Alexa, and all the verbal subservient assistants are women. Isn’t this normalizing sexism?”

Interspersed with candid interviews from corporate leaders, venture capitalists, journalists, activists and more, Lucie Green’s Silicon States paints a critical picture of exactly how much of a threat Big Tech poses to our values, our democracies, and our world at large. As the largely unregulated corporations promise us that technology will solve everything, Green’s book helps us think through what it is that we might have to give up in order for that to happen. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Swaddle: What motivated you to write a book about the threat that big tech companies pose to public life?

Lucie Greene: I started off quite agnostic. This is back in 2014, and I was a forecaster attending another tech conference. Peter Thiel, the famous billionaire venture capitalist, talked on stage casually about extending life spans and hacking aging. On another stage, Shervin Pishevar, the bombastic venture capitalist behind Uber among other ventures, talked casually about redrawing the world map, space, and time with Hyperloop. The confidence and vision struck me, but also the high-mindedness – there was a total disdain for governments and their ability to build the future. This conference occurred amid a perfect storm of announcements. Mark Zuckerberg announcing philanthropy on a scale unseen before. Facebook and Google both making lofty statements about bringing internet to emerging markets using floating balloons and other devices. It seemed like the ambition put forth was way bigger than what we’d come to know them for previously – as tech companies, as brands. Meanwhile they were building lavish temple-like headquarters in key cities.

Back to the term ‘agnostic.’ I really was quite neutral when I started looking at this issue. It’s important to remember that in 2014, the view of this group was quite different. What we see now — a landscape of hostility and criticism for the tech giants — has accelerated and hit critical mass. But back in 2014 and 2015, there was still a tremendous amount of enthusiasm and positivity for them and everything they were doing. And criticism was fairly nascent. In a way, my journey writing and researching this book, and exploring the ethical implications of their moves to transform civic life, has mirrored the journey of public consciousness. In those few years I have gone from broad positivity, to having deep concerns. Likewise, the touchpoints we have to this group have exploded, and thus the data points they own and are commercializing. Which is why we need to look at them now with more scrutiny.

The Swaddle: Most people see this as a macro issue, one that doesn’t affect them. I’ve heard people say, “So what if Facebook and Google have my data?” How would you argue against that?

LG: To an extent, the magnitude of the information Facebook and Google have is so great that it’s just difficult for people to contemplate fully. Likewise, there’s a feeling of powerlessness, which then stumbles in to apathy and fatalism – because let’s face it, today it is extremely difficult in most markets to live, work, and socialize without using these companies’ services and products several times a day. Once you start to pick away at this, it becomes hard to see a way out.

I think right now, all this data is being used to enhance services — it’s making things faster, more personalized, more convenient, so it’s easy to think that the situation is not that bad. The issue is that as these companies move into banking (Amazon, Apple), health (Google, Apple), city design (Alphabet-owned Sidewalk Labs) and have a greater hold on all our interactions and daily life (see Facebook’s Portal, which is a video communications home hub, and voice-activated cars using Amazon Alexa), there’s scope for de facto ‘sticks’ to be applied — for your health to affect your credit rating. For your productivity to be scored and affect your compensation.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Mom Tech Industry Needs a Revolution

Likewise, as these groups move into more surveillance and policing services, the cracks in AI and photo recognition — and their biases– are starting to show. Already it’s been found that facial recognition has racial bias and cannot accurately distinguish identities for ethnic minorities.

The Swaddle: Can you tell us a bit about your experiences while researching, traveling, and writing the book? Were there things that surprised you or worried you while you were working on this project?

LG: Interviewing Silicon Valley executives, and trying to get access to tech companies generally, brought to life the opacity and hubris of this group. For all their claims of being open, they are highly controlling of media and tend to hang back from interviews they cannot manage. They resist meaningful debate, or at least seem to think media critique of them is biased. The privilege and confidence of executives in their abilities, and tech’s abilities, shone through in interviews.

Meanwhile, spending a lot of time in San Francisco and Silicon Valley also brought to life the idyllic bubble that blinds these tech companies to the implications of their technologies. In San Francisco, headquarters serve artisan coffees to Prius-driving staff, while homeless people loiter on the streets. Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley towns, which are sunny, suburban, and low-rise, there’s little connection to ‘reality,’ or at least the full spectrum of realities that their technologies inhabit in the wider world. On the travel front: it was fascinating to visit both Cuba and India, outside the U.S., and how these companies were being perceived, and how they sit alongside Chinese tech giants in these regions. But also witness how truly global they are becoming.

The Swaddle: In the book, you imply there’s a shift, where tech companies are increasingly trying to shape not just our online interfaces, but the real world, through health care, infrastructure, education, energy, etc. What might our future look like if that happens? Or has it already?

LG: There are, of course, tremendous advances being made in these spaces thanks to tech, innovation, AI, and life sciences research being propelled by the tech companies. This could make health care more affordable, enable more personalization, prevention, and real breakthroughs in the environment, medicine, learning and more.

However, there are a few issues. One being that a lot of this is being driven by private companies, and so is inherently commercial in its ambition. It’s being devised by groups who are not diverse in background from ethnicity, to gender, to income. Which creates issues when you are trying to design inclusive public services. They are also moving very quickly without much oversight or transparency from government.

The Swaddle: India has one of the world’s largest internet populations. From your research and the time you spent here, can you share some insights about the dangers Silicon Valley tech companies might pose to developing economies?

LG: India has a dynamic, rich media landscape, a robust popular discourse and strong government – which means that it’s been able to maintain control of how the tech giants move into the market and retain competition. But this isn’t the case in economies with weaker democracies, corruption, fewer resources, and controlled media. [In these places], it’s easier with the ‘carrot’ of internet infrastructure and free connectivity for Big Tech companies to move in – in exchange for control of what that internet looks like. Often, this is a closed loop – it’s a mediated experience on the internet. As with Free Basics, the experience of the internet becomes Facebook [only]. Not the landscape we have in the U.S. where we can use Google, Yahoo, and any website we choose.

The Swaddle: You’ve talked about this idea of ‘tech colonialism’ — can you tell us a bit about what you mean by this?

LG: “Data is the new oil,” or so the saying goes. It’s a commodity. Tech companies are moving into new global economies (often without wide internet access) hoping to ‘land grab’ the biggest share of consumer habits, connections, and interactions by launching connectivity, hardware, platforms, and more. It’s different to their approach in places like the U.S. and the U.K., where they enter a much more crowded space. In places like sub-Saharan Africa, they are building the internet from the ground up. Often, with initiatives, they are presenting this like philanthropy – internet, the great unlocker and civilizer. They are imperializing the latest commodities, which is people’s data, in markets that are not yet connected fully.

The Swaddle: When we talk about data privacy, it’s rarely framed as a gender issue, but men are the ones who are building these tools, and are in charge of how they work. Zuckerberg and Bezos, for better or worse, are shaping our world today. I wonder if you can give us some insight into whether this impacts women specifically? Are women more vulnerable to the consequences of Big Tech?

LG: There are many ways in which we are seeing how bias is emerging in the internet around us, and it doesn’t stop with gender. These companies are predominantly white, and male, and populated by privileged, educated workers. This inevitably manifests in the systems, hardware, and platforms they design.

For example, Siri, Alexa, and all the verbal subservient assistants are women. Isn’t this normalizing sexism? Twitter continuously fails to address misogyny and bullying towards women. Amnesty International recently described the women’s experience on Twitter as “toxic,” talking about attacks as “digital violence.” When it comes to women’s health, tech was also famously behind – Apple was late to introduce women’s personal care and health to its monitoring tools on the iPhone. It’s biased in experiences, but it also means they are missing opportunities. As such, the most exciting companies in the female health tech start-up space are coming from female founders building their own offers. But this is not as progressed as it could be because VC funding is largely dominated by white men – which has led to companies like these not getting the backing or visibility they deserve. Thankfully, there are some really exciting new funds emerging focused on getting women, women of color, and more diverse founders backing for solutions.

Amnesty International recently described the women’s experience on Twitter as “toxic,” talking about attacks as “digital violence.”

The Swaddle: In the book, you point to the ways that women are largely absent from the Silicon Valley narrative of talented geniuses pushing the boundaries of what’s possible (who are mostly cis, white men). It’s difficult not to wonder what the fallout of this is? What are we losing out on because of this gender inequity?

LG: There is a huge mythology and success story attached to Silicon Valley tech companies and their leaders – and it’s going squarely to individuals, mostly white male. That message is incredibly powerful. What if you are not in this group and want to succeed? As the old saying goes, “if I can see it, I can be it.”

It’s also not accurate. Many of these companies were built on the input of female engineers and collaborators, which has been ignored. There’s a savior narrative often, when it comes to Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk, shipping in supplies to national disasters, which can be dangerous. It means that we do not question this group in the same way. For example, it’s only now that at places like Davos, thinkers and critics are pointing out that philanthropic donations are a drop in the ocean when it compares to how much these companies and individuals should be paying in taxes.

The Swaddle: Specifically in a post-MeToo moment, it seems that tech companies haven’t quite caught up to the cultural conversation, despite paying lip service to women and minorities. Particularly within the creative industry, where people are dependent on the gig economy, you present a number of troubling statistics. What are the factors that get ignored or looked over, when it comes to the tech industry and the women working within it?

LG: One example is the gig economy. Workers generally are weaker in this Wild West employment model, where many have scant rights or security and are moderated by ‘star’ user reviews. The situation gets worse when it comes to women workers in the gig economy feeling safe, protected, and able to raise complaints.

The power structure of leadership in this group of companies is also important to consider. The MeToo movement was about abuse of power, often by male leaders. And tech’s leadership is predominantly male. Already there have been mass walkouts by women at Google over seemingly relaxed (or moderate) treatment of complaints of this nature.

Related on The Swaddle:

Tech is Shaping a New Type of Sexuality

The Swaddle: Finally, what can be done about all of this? What should our governments and regulatory bodies be doing? And what can we, as consumers and users of these companies, do to ensure that our freedoms are not being curtailed?

LG: It’s difficult to know, but I would say first, become an informed consumer. Start switching off location settings. Take tech-time outs. Really read privacy policy when you click ‘yes’ to signing in to apps. And pay attention to the media. Ultimately, the biggest restraints on this group need to come from the government, which requires a strong government and democracy. Participate in elections. Vote. And demand a more robust tech policy – and that politicians understand and have clear strategies when it comes to ensuring fair competition, privacy, and that the best parts of the internet remain.

Nadia Nooreyezdan is The Swaddle's culture editor. Since graduating from Columbia Journalism School, she spends her time thinking about aliens, cyborgs, and social justice sci-fi. She's also working on a memoir about her family's journey from Iran to India.

Related

The Buzz Cut: ‘Avengers: Endgame’ Isn’t the Superhero Movie We Wanted