Sri Reddy's Troubled Exile

Was the MeToo movement too little, or was she too much?

The Symbol Who Wasn't

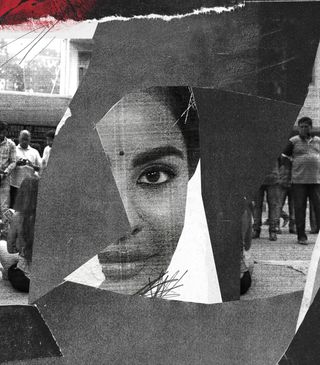

Sri Reddy’s is the story of how the face of a powerful feminist movement implodes. When the actress stripped in defiance of sexual exploitation in the Telugu film industry in 2017, she announced her intentions ahead of her act, so that the news crews were ready, waiting to see if she would really dare. She did. It was in front of the Movie Artistes’ Association (MAA), in Hyderabad’s shiny Jubilee Hills area. Reporters closed in on her as she took off each item of clothing, one by one, escalating her protest with each new set of eyes to bear witness. TV crews circled her like buzzards to carrion. She was at the end of her tether. Over half a decade later, she’s a forgotten piece of MeToo history. How does a protest like that vanish? How does a person like that vanish?

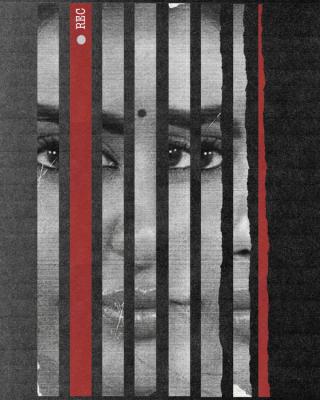

She says I can call her Sri. These days, she makes YouTube videos from her refuge in Chennai, having left her Hyderabad life – and the industry she fought for and with – behind. “I’m leading my life very happily. It took four years to come out of that black mark,” she says. But a few minutes later: “I’m not very happy in my life, mentally.” She says she misses her freedom. She doesn’t have good friends because she feels guilty if they bring up her past. “I’m doing my work, I’m earning good, I’m okay. But still I have a gap with society.”

When people recognize her in Chennai, she imagines what they’re thinking: This is that girl. The nude protest. The one who was “used” by everybody. When she goes to temples, the few times she steps out, she covers herself up. In real life, she keeps a low profile. On YouTube she cooks, she talks about feminism, makes beauty tutorials, goes through her exercise routine, does political commentary, and preaches devotional content. Her brand isn’t defined by any thematic consideration; it is whatever she’s feeling and thinking.

“They recognize me as a victim, they don’t know my talent."

In one of her many “village cooking” videos, she makes squid capsicum curry in a rustic setting, with earthen pots, banana leaves, and an open kitchen. The title of the video is tongue-in-cheek: “Naadhi chusara yentha pedhadhundhooo😜😳.” In Telugu, it means “did you see how big mine is?” Her saree is hitched up; her blouse is low-cut. This is the “glamor” component, she says – it’s what gets her views, because it’s what people expect from her. She calls it the “Sri Reddy flavor.”

Another video is a dramatic departure from this style. It’s an explainer: “Things You Need to Know About Anal Sex.” She’s seated at a table, wearing a plain tee, calm and composed, while she explains anal sex in a crude pidgin of Telugu interspersed with English words like “dick,” “ass,” and “poop.” She discusses who has anal sex, how many people have it, the stats, the health implications, and the aftercare. It's not perfectly accurate. It has none of the finesse of Instagram sex educators or influencers. But it’ll do for the more than 400,000 people who have viewed the video. The “Sri Reddy flavor” is in the choice of topic itself: she acknowledges that nobody would be surprised that someone like her is talking about anal sex. And so she does.

“They recognize me as a victim, they don’t know my talent,” she says, reflecting on her public image currently. Her YouTube videos have raked up a substantial following. For the magnitude of public disgrace she experienced, one might peek into her comments section with trepidation. But they would be mistaken: the comments are encouraging, affectionate, and gentle. “Take care, brave Sri ma’am.” Cut off from her family, lacking in friends, out of touch with the activists who backed her, these anonymous comments seem to be one of her only forms of support today. She claims that her protest made Tollywood wary, and women a tad safer. She says they invoke her name as a threat. But everyone distanced themselves from her. In the whole conversation, she’s only mentioned her YouTube followers with any affection. When someone falls from grace twice, like she did, they’re probably bound to end up lonely.

The Perfect Victim

In a way, she was alone all her life, but she made it work. She grew up in Vijayawada, a small city in Andhra Pradesh – not quite urbanized, but not quite rustic either. When her sister was born, her mother suffered from mental illness and she needed a few years to go away and get well. Sri Reddy was left with her father. She did the housework and the cooking. She wasn’t pampered much. She was a good student in school. She says her parents weren’t too attached to her.

She needed an out. She did a beauty course after her degree and opened a beauty parlor. Then, a famous news anchor stepped into her salon. The anchor told her she spoke Telugu well, she had the looks, and the TV world was where she belonged. “When she told me that, I couldn’t sleep. Hyderabad life seemed so exciting,” she said. The anchor gave her an address and a phone number.

She took the anchor up on it against her family’s will, went there, stayed in a hostel, and figured it out. She started out as a TV presenter. She recalls her father warning her about all that awaited her in the big bad world of Hyderabad’s media landscape. He told her: “Our people won’t accept this. Being a Reddy, how can we walk with our heads held high?” Everything he said would happen, ultimately did happen. “I don’t know what stars were aligned when he said this, but it happened exactly as he predicted. I am a ruined woman now.”

"The whole system was against her. They were waiting for her to make a mistake," says Tejaswini.

This overwhelmingly resigned demeanor isn’t what I expected while speaking to her. I had in mind the photographs and videos from when she planted herself at MAA’s premises. In them, she’s fierce, defiant, unbecoming. Her anger blazes. The news vans swarm her, cameras flash, journalists and videographers jostle to capture her. It is grotesque. My impression of her was cemented by her address to the crowd assembled at the scene: she said she was there so that the Telugu film industry can build itself over her corpse. She said she was doing it for the women in the industry, and that it was too late for her – she lost her dignity and her family’s. She challenged the industry to build a graveyard where she sat. Reporters – inching closer to her semi-nude body – repeatedly asked her why she was doing what she did. “I can’t break their buildings or set them on fire. I only have myself to protest with,” she responded. Her words landed like blows, her voice was hoarse from spitting them with fury – and a distinct sense of nothing to lose. She seemed, to me, like MeToo’s first martyr.

Her complaint was atypical. She confessed to acquiescing to directors’ quid pro quo proposals. She wasn’t ashamed of it. Her problem was that the industry had not held its end of the bargain, and that she didn’t end up getting any roles in the movies. She wanted to know why Telugu women were “cheated” this way, why there was no room in the industry for someone like her. She questioned why they were allowed to exploit women sexually and not have to answer to them after. She released screenshots of her chats with high-profile people. All this, with only minor roles in two small films to her name. She questioned the power dynamic confidently. That, to feminists and distant observers alike, was what made her stand out.

Obviously, this was a problem for those in power. Film families, producers, and directors in the industry denounced her; actresses denied legitimacy to her claims. Nobody who was anybody in the industry – not even fellow actresses – came to her defense. Instead, character artists, junior artistes, dubbing artists, and others with no name and no backing came out with their stories after Sri Reddy did. When MAA banned her citing her “cheap publicity” stunt, activists came to her defense. It was a symbiotic relationship: for Sri Reddy, the activists were a badge of respectability, ensuring she was taken seriously and her protest wouldn’t be for nought. For the feminists, Sri Reddy was the flashpoint around which movements are built; she was also the gateway into a rarefied world they had no access to and whose issues they couldn’t effectively address before she came along. Thanks to her, and everyone who came out after her, they learnt of the insidious “coordinator” system – in which middle-men acted as gatekeepers mediating outsiders’ access to directors and producers and solicited sexual favors to get people through the door.

The National Human Rights Commission soon got involved – it sent notices to the Government of Telangana and the Union Minister of Information and Broadcasting. Soon after, Sri was reinstated by MAA. She was felicitated by women’s groups. The Telugu film industry setting up internal complaints committees for sexual harassment complaints. A high-level committee was constituted to look into other complaints and assess the extent of the problem. It comprised 50 members from outside the industry, like NGOs, doctors, psychologists, former government officials, the works. Activists compiled their findings over nearly five years and submitted a report to the National Commission For Women.

All this legitimized Sri Reddy’s complaint in the public’s eyes. Until that point, this was the most progress any film industry had made in India with respect to MeToo – because it brought together a coalition of stakeholders against the entire juggernaut. For a time, Sri Reddy, backed by an army of seasoned feminist activists, succeeded in capturing public support against an industry whose propagation of rape culture and feudal caste pride was already an open secret. An uprising was underway, because everyone recognized the inherently subversive politics in her protest. It had the potential to catalyze similar movements in other states.

That’s when the other shoe dropped.

“Of course, you know the famous – or infamous – Pawan Kalyan incident. That was when it suddenly collapsed,” said Tejaswini Madabhushi, a core member of Hyderabad For Feminism, and one of the activists who worked closely with Sri Reddy. One day, without warning, Sri Reddy called the Telugu actor-politician Pawan Kalyan a “motherf*cker” and showed him the middle finger in her interviews. The director Ram Gopal Verma came forward to say that he was the one who had convinced her to do it – in response to Kalyan weighing in on her protest, opining that she should’ve gone to the police instead of the media. “... when RGV told me to use that expletive, I readily agreed. I also knew that this was the only way I can get powerful film families to speak about my issue. My intention was not to hurt anybody though,” she later told Times of India.

“The Telugu [film] industry is way too feudal and casteist. That is why she didn’t get any support from anywhere."

In some distorted way, the gimmick seemed to have been an attempt to grab eyeballs to the issue. But it backfired – badly. Pawan Kalyan is an industry colossus, powered by the dominant Kapu caste loyalty and their aspirations for political representation. He also belongs to the powerful film dynasty helmed by his brother, “Megastar” Chiranjeevi. Like many movie stars in the South, Pawan Kalyan began to leverage his celebrity into a promise for political representation – not only for the caste he was from, but he also campaigned on a platform of progressive inclusion for all. So when Sri Reddy zeroed in on him, legions of his fans came after her and everyone she was associated with. She had unleashed a beast.

In any case, the consensus was that she wasn’t strategic. That she was too volatile. Too impulsive. “We knew that many people were talking to [the women who spoke out], offering them various things, cajoling them, warning them, threatening them, tempting them with various things,” says A. Suneetha, feminist researcher and activist. So when Sri Reddy was unexpectedly at loggerheads with Pawan Kalyan, “the whole industry took that as an opportunity to come together and exert enormous pressure on the TV news channels to kill the issue.” Soon enough, Kalyan and his opponents tussled to position her as a pawn in their fight. The politics discredited – derailed – the feminism of it all. As Madabhushi put it: “the whole system was against her, they were waiting for her to make a mistake.”

All the momentum of the movement against sexual exploitation dried up. Politicians and industry members alike distanced themselves from the issue of sexual abuse in Tollywood, partly out of fear of what else Sri Reddy – who had become the face of the movement – might say about whom and partly out of reverence for the powerful actor whose name had been unexpectedly invoked. “The Telugu [film] industry is way too feudal and casteist. That is why she didn’t get any support from anywhere,” explains Madabhushi.

It didn’t matter that she had the backing of women’s groups – activists don’t ultimately influence a celebrity’s notoriety as much as the gossip rags and media do. The slut-shaming and discrediting resumed with even greater force. Interviewers asked her questions like how many people she slept with, whether she had any right to claim dignity, and worse. The goodwill she earned from the public evaporated. They wanted a perfect victim; what they got instead was an erratic, foul-mouthed woman who had attacked their favorite messiah. It changed how the general public looked back at what she did. Sri Reddy says that many women would confess to her in private that they supported her reasons for doing what she did – just not her methods. The “bad” woman with the good cause.

But what happened to the cause? Sri’s first undoing was succeeded by a second – one which splintered the feminist movement against the industry that she had played an indispensable role in igniting.

The Perfect Feminist

Today, she’s not in touch with her family. Even the anchor who gave her her first big break doesn’t want to be associated with her. She’s afraid of carrying the baggage of being the person who brought the blight that is Sri Reddy to the industry. “She begged me not to take her name anywhere. She even blackmailed me,” she recalls. Sri Reddy kept her promise – she never told me, or anyone, who this anchor was, out of respect for her as a woman, she says.

“There's always some form of intellectual arrogance in some of the feminists and left,” Vyjayanti remarks. I ask her if that alienated Sri Reddy further – “Undoubtedly yes,” she says.

There’s disagreement among feminists as to whether Sri Reddy knew the implications of what she was doing. One camp embraced her act as radically feminist. “It sent shockwaves through society. One has to acknowledge that we haven’t seen that kind of protest, especially in the South,” says Vasanthi Nimushakavi, a professor of constitutional law at NALSAR, who went on to conduct a study on 300 people’s experiences in the industry. “She had [the industry] completely blindsided, which is what was so amazing about it.” She said it instantly reminded them of the Manipur women’s “Indian Army Rape Us” protest. The first thing women’s groups did, adds A. Suneetha, was “not defend but interpret her act, and create a conversation about why women’s protest in these forms should be understood as feminist.

But to others, stripping half-naked was an act of passion, rage – brave, but lacking in intentional feminist consciousness. “We can’t call her a feminist… We feminists and activists took up the movement, but in my opinion Sri Reddy is not a feminist,” says Satyavati Kondaveeti, an activist from the Bhumika Women’s Collective. “She did it only for herself, out of anger. Afterwards it just became a movement.”

The difference between the two camps grew as they got to know Sri Reddy more: as an erratic, unpredictable person. One of the biggest points of contention was that Sri Reddy didn’t speak and behave like a feminist, even if her singular act of protest was inherently feminist. Should they claim her as one of their own, or take the movement forward without her?

“When 10 people want to work together, we take inputs from all 10 and form the final agenda… [But Sri Reddy] only did what she wanted to."

Despite her curiosity to learn about feminism from lifelong activists, there were lapses. She’d accuse other women of sleeping their way up. She’d portray herself as the only person leading the movement. She’d alienate other women who came forward. When Chandramukhi Muvvala, an actress and trans rights activist, met Sri Reddy, she pledged her and the entire trans community’s support. But the solidarity wasn’t reciprocated. “When 10 people sit together and want to work together, we take inputs from all 10 and form the final agenda… [But] she only did what she wanted to,” Muvvala said.

But maybe, expecting activism from an aspiring actor was misplaced to begin with – there’s arguably nothing wrong with protesting for oneself, as some people felt. Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli, a co-founder of the Telangana Hijra Intersex Transgender Samiti, calls it gatekeeping. “Sri Reddy was not from an activist background. She was an aspiring energetic actor who clearly alleged sexual harassment by some powerful men in the Telugu film industry. She really needed truly feminist hand-holding – considerate, compassionate and humane,” says Mogli. I get the sense that things got heated. “A certain privileged dominant landlord-caste 'left' feminist made it all about herself... Neither she nor her minions were from the film industry with any lived realities whatsoever. It was about them hobnobbing with the government, with the media," she mocked. The person in question wasn't available for comment.

This was all reflective of the ongoing debate within activist circles: how gatekeeping over terminology, praxis, and political correctness preclude solidarity and mass movement-building. Some feminists seemingly wanted Sri Reddy to play her part: that of a symbol, not of a voice.

But what does one do with a voice as unstable – even at times harmful – as hers?

Another fracture came at the heels of a high-profile caste violence news story. “After that Prannay-Amrutha case, she made some uncharitable comments… I don’t know what her motivations were but by then she was quite abandoned by the self-proclaimed left feminists,” Mogli said. Prannay, a Dalit man, had been murdered by his wife Amrutha’s dominant caste family. It is one of the many incidents dotting the bloody history of caste violence and atrocities in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Sri Reddy criticized Amrutha in a Facebook post, then later deleted it and retracted her comments, along with an apology in which she extended her support for Amrutha. But it raised an important question: where do activists draw the line when mentoring a fledgling activist? Surely this crossed over into territory which couldn’t just be called imperfect – it was actively harmful to the intersectional feminist cause.

Then again, Sri Reddy’s background makes this unsurprising. An upper-caste Reddy woman, from small-town Vijayawada, imbued with her father’s warning about her carrying their pride as a Reddy. If the movement was truly intersectional, shouldn’t it have accounted for this – perhaps even deprogrammed her from it? It wouldn’t have been an easy task, but Mogli thinks this was where the movement failed: “Activism is not about doing easy things, plucking low-hanging fruits,” she says.

Slowly, but surely, the movement that coalesced around her began to distance itself from her. Vasudha Nagaraj was Sri Reddy’s lawyer, who petitioned on her behalf and represented her in a high-profile defamation case filed against Sri Reddy. She later withdrew her legal services. She was once the first person Sri Reddy thanked in press conferences. Now, they no longer speak to each other. Nagaraj declined to speak on the record for this piece.

Sri Reddy was an existential question for feminist groups. What would they be seen to be standing for, if they continued their association with her? On the other hand, what would they be if they didn’t? Could they associate with the cause without associating with the person? “There's always some form of intellectual arrogance in some feminists in the left,” Mogli remarks. I ask if that alienated Sri Reddy further – “Undoubtedly yes,” she says.

Ostracized by the film world, distanced by the feminists who came to her rescue. “Very quickly she became all alone. Very quickly she lost all the support,” says Madabhushi.

Meanwhile, as the movement imploded around Sri Reddy, the film industry came away relatively unscathed. No big names – or small – were implicated. If it was a shame collectively carried, then nobody in particular could be said to carry it.

The Aftermath

Presently, Sri Reddy resolutely espouses Sanatana Dharma, a core part of Hindutva ideology. Images of her firebrand act of defiance in my mind give way to something more uncomfortable and difficult to grasp.

So far, I liked her. But now, I’m disconcerted by her. A day after the temple consecration ceremony in Ayodhya, she posted a video on X holding up a saffron flag and reciting a speech about Ram. For nearly thirty minutes in our conversation, she rhapsodizes to me about Sanatana Dharma and what it means to her. She regurgitates Hindu nationalist talking points about Muslim kings, the crimes their armies allegedly committed against women, the army of sadhus that retaliated.

“I still don’t know what pure love is. That’s why I’ve connected with God – that is the purest love in the world."

It wasn’t always like this. Religion was a commonplace thing in her household. She returned to it more seriously in her exile.

In this phase of her life, she has rejected lovers, she’s given up on dating, she’s estranged from her family. She says she “couldn’t” marry anybody, she only has suitors who want to casually date her. But she doesn’t want to be “used” or “cheated” again. “I still don’t know what pure love is. That’s why I’ve connected with God – that is the purest love in the world,” she says. After all her trouble with people, she realized that with God, there’s no fakeness, no expectation of reciprocity through gifts, dowry, or beauty. Unlike people, God’s love isn’t conditional upon what she can give.

The brazen insouciance she once had for the cause is clearly gone. Her newfound faith is her shield. “Today, people comment and ask: do you have a right to support Sanatana Dharma, when you have been—”

She pauses here. She’s looking for a word she knows in Telugu, to try and translate it. I tell her that’s fine, I speak Telugu too. There’s a pause: “Are you a Telugu girl?” she asks. I say yes. Her demeanor shifts instantly, I hear the tension leaving her voice. “Until now, I was struggling in English and you didn’t say a word,” she said, teasing me. I heard a smile entering her voice. From this point, she speaks in a manner reminiscent of her news anchor roots, and I’m momentarily disarmed despite what she’s talking about. The Telugu words she uses are sophisticated, sometimes even anachronistic, the way a news anchor’s language would be.

She says people don’t readily accept her into the Sanatana Dharma fold because of her past. But she says it doesn’t matter to her, that her belief is “purely spiritual.” When I ask her whether her belief in Sanatana Dharma is political, I have the Hindu nationalist political landscape in the back of my mind, but she doesn’t seem to. She doesn’t broach the subject of national politics (as opposed to regional politics) in any of her online content either. If her spiritual Hindu beliefs were political, she says, then it wouldn’t be possible for her political support to lie with the YSR-Congress – a party in Andhra Pradesh led by dominant caste Christians. In previous interviews, she has expressed admiration for Jayalalitha (a Hindu Brahmin politician) and MK Karunanidhi (a leader of the anti-Brahmin struggle in Tamil Nadu) alike.

But she does want to enter politics some day. It’s hard not to see her political aspirations inspired by actor-turned-politician Jayalalitha. In the Tamil Nadu Assembly, Jayalalitha was infamously disrobed by unruly opposition party members. Shaking with rage and humiliation, she posed for a photograph in a state of disarray. Overnight, her image as merely an actor’s concubine changed: She became “Amma,” and a nation rose up to defend her honor as she ascended to the Chief Minister’s seat, desexualizing her in the process of restoring her dignity. In Sri Reddy’s case, the disrobing was characterized by one crucial difference: she did it to herself, in an act of reclaiming her agency from an industry that sexualized her too much. In a different world it might have lent her political credibility. Not in this one.

Those who worked with her also compare her with Kangana Ranaut. Ranaut’s present endorsement of Sanatana Dharma carries a similar backstory: her humble beginnings, initially progressive leanings, and de facto expulsion from Bollywood for speaking against it gave her the mileage to acquire a right-wing fandom, primed as it was against Bollywood’s exclusivity. Both Ranaut and Sri Reddy were scrappy outsiders to the elite and impossible world of the movies, ruled by sophisticated A-list dynasties and feudalism.

Unlike Ranaut, however, Sri Reddy may never “make it” into the conservative political fold despite her religious bent, and she’ll likely never regain the goodwill she had with the progressives because of it. She knows this too: she’s aware that political parties might be wary of her past, and more importantly, of her. She’s too green, too unpredictable, too unmarried. As a single lady who has “done glamor and MeToo,” as she puts it, she doesn’t belong. What if she accuses the party?

Hence the “Sri Reddy flavor,” even in her political commentary on her YouTube and X accounts, leverages her own unique brand. In some videos, she styles herself like her cooking content and viciously attacks Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Jagan Mohan Reddy’s political rivals, while also debating issues like student and farmer suicides. She titillates, giggles, twirls her hair, and swears obscenely, even as she’s performing religious rituals and making political commentary. It’s an ugly world, she says, but she isn’t afraid because she has nothing to lose. “Politicians… don’t have a heart. They do a lot of dirty work. But I don’t have anybody they can blackmail. They can’t do anything to my family – because I don’t have a family.”

"I thought it’s enough if people believed me. But Bollywood feminists who call themselves feminists said I did it for publicity… They call themselves victims but don’t acknowledge others as victims," says Sri Reddy.

I’m curious about how her isolation and her resulting borderline-fundamentalist turn impacted her feminism. I’m startled by her response. “Wearing small clothes, sleeping with ten people is fashionable now. Only men can cheat women, only women are victims – but there are women who cheat men too, is this women empowerment?” she asks. Suddenly, I feel like I’m listening to a fringe YouTube personality.

She uses a term – “Bollywood feminism” – which she defines as “wearing short clothes to hospitals, schools, colleges, roads… playing the victim card everywhere.” She’s citing examples like Four More Shots Please to make her point. I remind her that many of her detractors used the same moral criticisms against her: that her protest wasn’t the right kind, not the right place, but that many feminists looked up to her because of it. But she says she’s different: when she made the choices she did, she was honest about it, and she was reacting to exploitation, which makes her and others like her “real victims.”

She’s never been married, but she’s very concerned about what women are doing in their marriages – abandoning them too easily, working too many hours, complaining about in-laws. “What do you say?” she finally asks me. I tell her I don’t agree. I tell her marriage—

She interrupts. She says feminists rile up women to leave their otherwise well-adjusted lives. There’s a defensive conservatism to her stance (she admires her grandmother as a feminist for not leaving her grandfather in difficult times), which makes sense to me later. But at that point, I wonder if I’ve misjudged her completely.

Is it feminism to break things, take off your clothes, wear jeans? She wants to know. I’m more than a bit surprised to hear all of this coming from her. “Feminism is asking for rights. If anyone asks for sexual favors, kill them if you have a gun, that’s not wrong… My feminism is clear to me. I want to teach others what feminism is,” she says. At this point, I hope she doesn’t. But hasn’t she already?

She is a fringe YouTube personality, I realize. This is her life now: she talks with an audience who doesn’t talk back. She speaks into the void, and there is nobody remaining in her life – not family, not the media, not feminists – to question, challenge, rebut, or debate her.

I ask her if she would call herself a feminist. She says yes – kind of. “I love being a feminist. But since there is a wrong meaning of feminism now, I’m not a Bollywood feminist, I’m a separate feminist. I have patience and respect for sentiments and spirituality.” She compares herself to kali devi, the Hindu goddess who destroys her detractors through violence.

It starts to make sense: when she’s calling out “Bollywood feminism,” she’s calling out the mainstreaming of feminism, its banality – how girlboss-y it is, how depoliticized, how lifestyle-ified. She’s just not articulating it in those words, but her anger and hurt about it is clear. She’s particularly resentful of a specific actress who discredited her, but went on to support MeToo in Bollywood. I ask her if she’s disappointed that when it mattered, Bollywood feminists, as she calls them, didn’t come to her support. “I didn’t do MeToo expecting anybody’s support. I knew there was more to lose than to gain,” she tells me. “I knew everyone, including my parents, would suffer, but I decided and did it. I thought it’s enough if people believed me. But Bollywood feminists who call themselves feminists said I did it for publicity… They call themselves victims but don’t acknowledge others as victims.”

Personal Vs Political

Controversy’s child, scandal’s lightning rod, MeToo’s dark horse. Sri Reddy is recognized as a whistleblower, a paradigm shift, a historic moment. I’ve heard people describe her as a goddess and a pornstar in the same breath. Everyone says her protest was the most significant thing to have happened in the Telugu film industry. They say she did the bravest thing, something they couldn’t imagine themselves doing. But was it all for nothing?

Nimushakavi doesn’t think so. “You can’t ask people to go to a complaint committee and not protest: that was a very important idea to put across… you can’t lock up these politics in some legislation or committee.” Sri Reddy’s protest was more of a provocation. She didn’t come armed with the discourse, the feminist-speak. Instead, she spits on political correctness. She is provocative and sly. She cautions others against showing skin and posts risqué selfies on Instagram. She thinks feminists break marriages, whilst remaining single herself. She tested the limits of solidarity and activism. The internal squabbles, the debates on language, the propriety politics.

No wonder, then, that she is all alone, in a different city, in an unnamed area, making YouTube shorts without a crew, avoiding everyone from her past life, abrasive to efforts to contact her, no longer in touch with anybody from the women’s movement she once sought refuge in. Her first act of defiance was disobeying her father. Her second was the protest. The third was alienating the feminists who backed her.

She invokes the religious concept of dharma when she looks back on her father’s prophecy. She should have respected and obeyed her elders – whatever happened to her now is her own fault, she thinks. This is a lot of self-blaming talk for someone who used to have so much moral conviction about her actions. But again, she’s not somebody who easily ascribes to a polar framework. Politics, morality, feminism and sexuality aren’t a spectrum in her worldview: they’re a constellation. The guiding principle is entropy.

For the briefly hopeful impact others say her protest had, it’s the protest she attributes to things going irreversibly wrong for her. “Maybe one day that sacrifice will give a good result,” she says. “I’m waiting.”

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.