The World Needs More Research Into Stillbirth

Doctors lack reliable methods to predict — and prevent — these tragedies.

Stillbirth is a devastating complication of pregnancy that affects millions of women globally each year. It is defined as a baby born showing no signs of life where delivery occurred at or after six months (24 weeks) of pregnancy. And in the UK, 90-95% of stillbirths happen before the onset of labor.

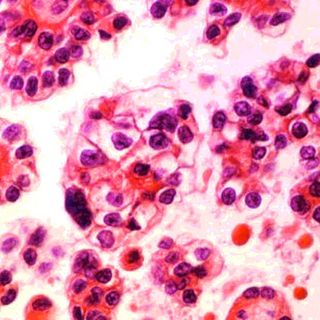

There are many different reasons why a baby dies in the womb. In a minority of stillbirths (less than 10%), the baby has a genetic condition or a lethal congenital abnormality. And it is only in a minority of cases that the cause of death is completely understood – for example where the mother has an autoimmune condition which produces an antibody that crosses the placenta and leads to death from heart failure in the baby. However, in the majority of cases, the cause of death is not fully understood.

In some there may be a risk factor, such as poor growth of the baby – but many poorly grown babies survive. Hence, it remains unclear why one poorly grown baby might be born live but another stillborn. In a sizeable proportion of cases the death is completely unexplained. The baby dies and, despite thorough investigation, there is no explanation or risk factor whatsoever. One can only imagine what parents go through who experience such a catastrophe with no understanding of why it happened.

When we consider the more than 3,000 stillbirths that happen in the UK each year, many would be considered potentially preventable. This is particularly true of losses that occur near the end of the pregnancy. About one-third of these stillbirths occur at or after 37 weeks, which is the threshold for defining a pregnancy at term. This amounts to more than 1,000 women a year. Again, a large majority of these cases have no underlying condition. If we could identify the babies at high risk of term stillbirth, their deaths could easily be prevented by early delivery.

[Ed. note: India accounts for 22.6% of the world’s stillbirths — more than is proportionate for a country that makes up 17.7% of the global population.]

Addressing the unmet need

These facts underpin the key barriers to progress. We do not have tests that reliably predict babies at high risk of stillbirth. If we did, we could use the test, deliver high-risk pregnancies early and save a life. But the tests we have do not work well. Currently an army of midwives is sent out to measure the size of the “bump”, from the pubic bone to the top of the womb, despite the fact that we know this test performs poorly in detecting poorly grown babies. Scans are normal in many women who go on to experience a stillbirth and are abnormal in many normal pregnancies, leading to intervention in healthy women who would otherwise never have had a problem.

So how do we move forward? There are three key elements. First, make sure that current patterns of care that are known to reduce stillbirth risk, such as optimizing care of pregnant women with diabetes are applied consistently. Second, learn from mistakes such as the failure to respond appropriately to risk factors, including women reporting reduced movements of a baby. Whenever a loss occurs, we should have an open and honest assessment of the care to identify any weaknesses that may have contributed to the loss. One of the ways a tragedy can be made worse is to fail to learn from them where they were potentially avoidable. Third, better methods of screening women and identifying and managing high-risk pregnancies must be developed. This is a focus of research in Cambridge, and we recently reported on combining ultrasound scans with blood tests to identify high-risk women.

The case for improving the research base is overwhelming. In so many areas of medicine, the gains from research are somewhat marginal. We apply interventions to those who have lived a life and we achieve a modest extension to that life. In the case of stillbirth there is a whole life to be gained if we get it right. And, if we do not improve what we are currently doing, we can easily end up intervening in cases where it is not required. This can lead to a lifetime of consequences. Unnecessary early delivery causes short-term complications and even impacts school performance years later.

But in the medical world in the 21st century, a world of personalized and precision medicine, the primary tool for screening for stillbirth is still a tape measure. It is symptomatic of the problem that this is the cornerstone of screening for such a devastating and relatively common condition.

This article is republished from The Conversation.

Gordon Smith is the head of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Cambridge.

Related

Parent‑Child Bond During Middle School Years Can Predict Depression, Anxiety in Teens