Tell Me More: Talking Dissent and Hope In Climate Activism With Tamseel Hussain

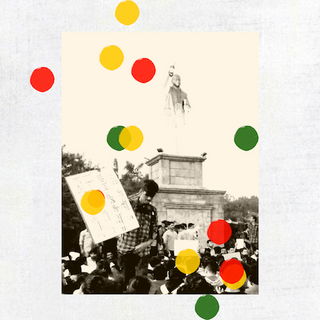

“Now, you actually see young, enthusiastic people leading protests against resource exploitation.”

In The Swaddle’s interview series Tell Me More, we discuss crucial cultural topics with people whose work pushes societal boundaries.

Tamseel Hussain is the founder of Let Me Breathe — a platform that tells video stories about pollution, climate change and sustainability. He has worked with organisations like Change.org, Oxfam India, and with tech companies, students, policymakers and media houses in India, South East and the Middle East. He has written for CNN International, The Guardian and Channel News Asia. The Swaddle’s Aditi Murti spoke to Tamseel about India’s anti-EIA draft protests and the future of climate activism.

The Swaddle: Why did you choose to document stories related to climate change and the environment in particular?

Tamseel Hussain: What we do with Let Me Breathe is allow people to tell stories about the environment via their phones. I remember, back in October 2017, around when we started, air pollution was pretty awful but back then, only a few experts cared. Over 2018-2020, people started taking pollution more seriously — only after several organizations and activists spoke up about it. Our goal was to make sure that we cover people’s personal stories, inform them on data so that they can start taking care of themselves. We believe in collective thought — behavioral changes in people and the Government goes hand in hand. So that’s the kind of work we do. We make both worlds meet through storytelling.

TS: A big part of the work Let Me Breathe did this year was to raise awareness and advocacy against the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Draft 2020. What was that like?

TH: So the Centre for Policy Research (CCR) put together a letter which highlighted what was wrong with the EIA 2020 draft, and we pushed it heavily via social media, website and newsletters. We did this alongside a few other organizations like Fridays For Future and Let India Breathe, in order to make sure the letter was going out everywhere and that all angles to the EIA were explained properly.

Then, a lot of users showed up to our website demanding action, so we continued to gather stories about the EIA. Even a lot of universities and college students were coming together and making sure that they sent that email. I think we had about half a million unique visits to the letter we’d hosted on our site, and overall the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change received 2 million letters by various people, experts and organisations registering their critique of the EIA 2020 draft.

TS: So the EIA draft was a bit of a turning point for environmental activism in India, specifically due to the enormous response it received from a young, urban Indian audience. Do you have any theories as to why this draft captured their attention?

TH: Climate activism in general is being led by Gen Z, right — the generation after the millenials. This has been brewing because, well, the kids know that generations before them destroyed the world they’ll inhabit someday. I think even before the EIA, there was a massive spike in school-going kids learning about and spreading awareness about the environment. Like 17-18 year old kids who really took to social media and technology in order to make sure that voices were heard. Like earlier, say six, seven years earlier, you would not see movements being built like this. Complex policies are being broken down for movements, and people are making an effort to understand.

Related on The Swaddle:

When We Destroy Forests, We Lose Millennia of Data Chronicling Earth, Human History

TS: Covid19 made it necessary to build a lot of these movements online. How did the internet lend itself to the act of protest with very minimal on-ground protests to accompany it?

TH: Everything was happening online in 2020, right? Like that time when cities were shot and you saw birds and animals roam about freely without any traffic on the road. Plus, you have so many people now who are super tech savvy. They know how to use online mediums like Twitter and Instagram. They’re aware of the power of influencing online and of how to utilize influencers to put out data and information. This makes people share and post more — as much as they can.

That sort of social media movement is balanced out with fact-checking. You see a massive spike in online activism when it comes to climate action, but there’s quite a bit of trouble with fact-checking the information posted. In this case, I think having a very engaged community of citizen journalists fact-check is vital, as they’re driven enough to make sure that the information coming out is data-driven.

When you see something like that, you want to join in! And so, you actually see behavior change through online movements, right? This is something that’s unimaginable, right? Behavior change usually happens through platforms like Netflix. You see something and there’s a trend that makes you change, but now the same is happening with consistent storytelling online. If people are blogging, sharing pictures with people, sharing videos, creating a behavior change, other people want to leave the baseline behind because they’ve seen someone else do it. It’s like gratification. And then you suddenly realize that you’re in a collective movement.

TS: Do you see citizen journalism as a form of dissent?

I don’t think citizen journalism can be a means of protest. Journalism needs to be objective. But it’s an incredible means to use phones and any other gadgets they have to create community-driven projects. Like for example, during the pandemic, you actually had doctors taking the lead and breaking myths! Even when it comes to environment and pollution-based news, there’s this one piece of fake news that makes the rounds each year — about an accident leading to cars piled up on top of one other due to the smog. But, then that’s dispelled quickly now because you have a community hunting down the source of the video to confirm it. If you have more informed citizens, all storytelling slowly starts to become more reliable. I see it as breaking away from traditional media structures in a way, which really helps.

TS: Okay, but here I’d like to point out that breaking away from traditional media structures is a form of dissent, don’t you think?

TH: That I agree with. I remember a media house asking me once about how they could use Youtube and Facebook to add revenue to traditional media broadcasts, which I found very interesting. So yeah, I think using technology to do citizen journalism is definitely one of many forms of dissent that can shake up things.

Related on The Swaddle:

TS: Coming back to the EIA 2020 campaigns, I remember it as significantly urban and English-language focused. How do you see online climate activism pushing into non-urban, non-English spaces over time?

TH: As technology gets more accessible and data becomes more readily available, I think these structures are dissolving on their own. I see video as a powerful medium to make regional language stories, because more people will watch it for sure. I remember Tamil Nadu having a massive anti-EIA movement, and a significant chunk of it wasn’t in English, but in Tamil. I’m confident about Whatsapp and video being strong means for dispensing information across language and location divides in India.

TS: What major challenges do you see with respect to India’s climate situation in 2021?

TH: The big-picture challenge I see is the idea of sustainable development. As a developing country, we need development and progress, but we can’t let go of sustainability during a climate crisis. Making both worlds meet is going to be the biggest challenge, and will be the biggest highlight of 2021 and beyond.

But I have faith. The biggest protest happening right now is in Goa, and related to coal. Can you believe it? I couldn’t have imagined how people would come together and talk about coal ten years ago because it’s not a very sexy topic. But now, you actually see young, enthusiastic people leading protests against resource exploitation. There’s young kids asking and questioning why they don’t have parks to play in. They’re getting their parents involved in thinking about access to greener spaces. That’s going to be an interesting transition.

And what do you see as the future of Indian environmental/climate activism in 2021 and beyond?

TH: I’m hoping that more politicians give more importance to climate activism and incorporate it into their manifestos and policy-making. You already saw it happen with Joe Biden, who’s striving to make several climate-action policies. I remember the Indian Vice President also tweeting about sustainable development, which was great! A lot of leaders will be expected to take a stand on environment because that’s something that communities want more and more at a local level, at the city level, and at the village level.

I also think there’s going to be this balance. Climate movements will continue to build in hyper-local regions more frequently, and speaking about climate change will becomes more important — even glamorous in urban spaces. I think there’s going to be more climate-related activist-tainment (activist-produced entertainment) and more brands and companies are going to jump on considering climate activism far more seriously. It’ll mirror the way fashion adopted activism and sold clothes. So yeah, a shift is happening.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

What This Year’s Protest Language Revealed About Societal Outrage In India