The Legendary Parties of Bombay's Aughts

Bombay's parties were messy, debaucherous, and real. But were they really more fun? We asked models, actors, musicians, DJs, and beautiful people to tell us about the early-aughts scene.

In Feroz Khan’s Janbaaz, the song ‘Give Me Love,’ or as more famously known — ‘Pyaar Do, Pyaar Lo’ begins with an egg cracking in slow motion. A young Anil Kapoor smokes a cigarette, wearing tight shots, as dizzying visuals of a variety of dancers form the foreground. Actors Shakti Kapoor and Feroze Khan, cigars in tow, watch young Black, white and brown men and women in leopard and zebra prints, headbands, and shimmering sequins and rhinestones sing “we dancing our lifetimes a way, and living our lives for today.” An air of abandon and debauchery spills through the music video, which was filmed at Studio 29. At this old discotheque, started by Sabira Merchant, cascading bubbles fell on dancers, smoke machines clouded their feet, jazz bands performed elaborate sets and dance floors lit up. “Studio 29 was the fucking place to be at in the 80s,” says theater actor Denzil Smith.

Two decades later, at the ‘Ode to Studio 29’ party at Zenzi Mills in 2009, there’s hazy footage of party goers ballooning in and out of the fish-eye frame, reminiscent of the hedonistic abandon from the song 'Koi Kahe Kehta Rahe' in Farhan Akhtar’s 2001 magnum opus Dil Chahta Hai, featuring a young Aamir Khan, Suchitra Pillai, Saif Ali Khan and Akshaye Khanna. In the footage, a shiny disco ball spins rapidly, punctuated by disco funk beats in a sepia toned montage from a party held at Zenzi Mills — the bigger and larger nightclub compared to its humble origins on Waterfield Road, Bandra. Neither Zenzi Mills nor Studio 29 exist today: they only remain in the form of hazy pictures, audio recordings and oral legends. This was a time when Bandra was in fact a sleepy suburb that gradually turned into an alternative haven for young and hungry artists, creative mavericks and advertising professionals. As the story goes for many gentrified suburbs today, rent was cheap, and partying was even cheaper.

The party, thrown by owners Anil Kably and his Dutch co-owner Matan Schabracq, celebrated Studio 29, which used to be located at the International Hotel on Marine Drive. At this Zenzi Mills party, the dance floor is made up of glowing squares that light up when you step on them; and before ‘projection mapping’ was a thing, a continuous display of cartoons splashed the walls. As the camera wades through a crowd of revellers, there’s stilettos twisting, boots thumping; as sweaty bodies throw their fists in the air, pirouette and grind against each other.

“You could walk into [Zenzi] alone and by the end of the evening you’re surely going to make some friends,” said Kris Correya, Zenzi’s Resident DJ who can be seen at the deck, spinning disco tunes on vinyl along with Jo Azarado, Studio 29’s Resident DJ. And that's the sentiment that many party goers agree with. For Denzil Smith, “whatever happened was avant-garde. We just lived, and [everything we] did was an extension of what we liked.” So they hosted art exhibitions like Naresh Fernandes’ photographic research into Bombay’s Jazz history, before that research culminated into Fernandes’ book Taj Mahal Foxtrot, and CP Surendran’s poetry paired with jazz music, among other efforts to blend musical genres with art. Then, there were Open Mind Nights, where musicians and bands, now known as Shaai’r and Func, Madboy Mink and Ankur Tewari, performed their experimental sets; on other nights poet and novelist Jeet Thayil, hosted the ‘Art of Noise’ events, where dissonance was encouraged. During a party that was an Ode to Andy Warhol’s The Factory, Denzil famously performed Allen Ginsberg’s "'Howl,' with the backing of a rock band” for 22 full minutes — “brace yourselves, it’s a long one,” he roars.

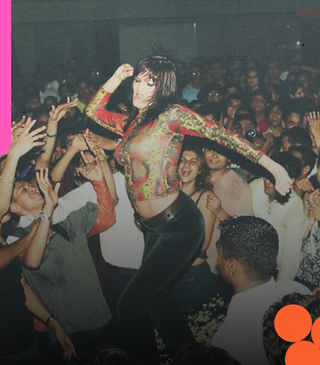

But Zenzi wasn’t the only place where a ‘sub-culture’ was taking shape. Fire N’ Ice was an institution for many in the city. It was a young, hip and massive warehouse in Lower Parel that hosted many infamous themed nights and DJs. On one such Bollywood themed Chandni Bar nights, Yana Gupta of ‘Babuji Zara Dheere Chalo’ fame can be seen dancing atop the bar and duplicate actors who walked around the party. “It was an idea whose time had come,” says Vishal Shetty, one of the owners of this old haunt. Models and VJs of Bombay’s heyday were roped in as ‘ambassadors’ who were enlisted to curate their own invitation lists. Model Carol Gracias remembers the opulence of it all — “everything was excess - the way people dressed... to the music, to the alcohol, copious amounts of everything was consumed.” The fashion was leather, lycra, cowboy hats and glitter, lots of glitter.

Many remember venues like J49, B69, Olive, Redlight and Earthquake, to name a few. Some were havens for up and coming musicians to experiment with groundbreaking musical styles. B69, was located by a seedy massage parlour with a liquor shop downstairs. People deliberately underdressed, and venues took curatorial risks by platforming metal, punk and rock performers. In the midst of a mosh pit and one such punk show, musician Suman Sridhar recalls subverting and combining genres to do an operatic solo performance at B69. For Sridhar, “punk is not a genre, it’s an attitude,” and venues like B69 were crucial spaces that actively built a community of young musicians who were irreverent, dissonant and experimental.

Similarly, Tejas Mangeshkar recalls how Bhavishyavani Future Soundz started — from the humble origins of Alvarez house, a hub for Bandra’s madhatters where a group of friends would regularly get together to “play music of our liking,” which was influenced by UK drum & bass, electronic, garage, and breakbeat. This was the era of Jhankaar Beats, where boomboxes installed in autorickshaws and taxis zoomed through the city, blasting remix tunes, as 5 rupee coins danced on the surface of the speakers. For Tejas, design was central to their process of curating a culture, consciously cultivated around an Indian design aesthetic that was local and experimental on multiple layers — from indic fonts to edgy fusions, to multi-functional flyers that doubled as roach papers, soft pornography on posters where “if you really squint your eyes you’ll see a blowjob,” and even wholesale wedding cards printed in Girgaon Chowpatty, as invites to an Indian wedding-themed party. The invites were dished out in an analog fashion. Calls on landlines, messages to pagers and later, drop locations on old Nokias.

“... there was a thrill reaching these venues in an analog fashion,” Ankur Tewari recalls. Raves were a big part of the city’s outskirts, starting out with a modest group of 20 people, and gradually becoming bigger raves of over a 100 people. The landmarks were hand-drawn on paper maps, toilet paper rolls stashed on mud roads until eventually, the thumping bass in obscure locations outside the city led you to the party. A big part of the experience was the music, the location and undeniably, the paraphernalia too. But beyond that, it was arguably the sense of anonymity, safety and community of diverse groups of people with different musical interests banding together. “We had more liberal philosophies, [came from] families with mixed marriages, and migrants to Bombay,” says artist Mandovi Menon.

“I’ve been a raver I’d proudly say for over 28-30 years,” says model and actor Suchitra Pillai. This was when MTV and Channel V hosted frequent roadshows and events across cities, so for the VJs, partying was actually work. The World’s Longest Party, was one such party, held in Delhi in the quest to achieve the title of being, well, the ‘Longest Party’ in the Guinness Book of World Records. It was a fond memory for many. Nikhil Chinapa recalls that evening as his favourite night with the late Nafisa Joseph, Cyrus Broacha remembers millions of people being involved, while Cyrus Sahukar looks back on the line that ran in kilometers outside the premise for a coveted ticket into this mammoth affair. There’s a general air of nostalgia that tints these anecdotes — a reminder that in 2024, nostalgia is all that's left.

At the heart of these recollections is a sense of unfiltered freedom and spontaneity—an era when parties became cultural milestones. The legendary parties of Bombay’s aughts were more than just hedonistic escapades—they were cultural crucibles where music, art, fashion, and community converged to create moments of unforgettable magic. These venues went on to create vibrant expressions of a city that embraced rebellion, and experimentation. Though many of these spaces have now faded into urban folklore, their legacy lives on, through stories, sounds, and memories that shaped an era of creative abandon before Instagram tinted filters took over.

Vasudhaa Narayanan is the Creative Director at The Swaddle. She explores the complexity of identity, domesticity, and gender through the visual arts medium.