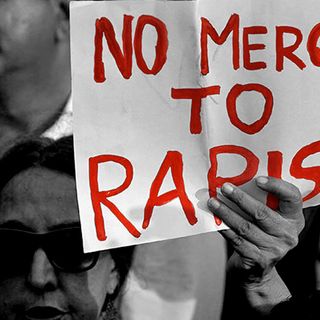

The Many Things Wrong With India’s First Sex Offenders Registry

It’s emotionally satisfying, but deeply flawed.

This Thursday, the Central government announced India’s first national sex offenders registry, which contains the names and details of 450,000 convicted offenders already. The registry, to be maintained by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), includes offenders’ names, photographs, residential addresses, fingerprints, DNA samples, and PAN and Aadhaar card details. Unlike the US, however, where this information is public, the Home Ministry has stated that only law enforcement agencies will be able to access the database for investigation purposes. The offenders’ details will be stored for a minimum of 15 years, depending on their classification as either “low,” “moderate,” or “high danger” on the basis of their criminal history. Juvenile offenders may also be included in the registry in the future.

At face-value, this registry seems like a good thing — finally our government is being proactive about protecting women and children. It feels satisfying — it feels like some kind of justice. But if we look closer, at the loopholes, the flaws, and the circumstances in which this pretty hasty decision was made, the conclusion changes.

This sex offender registry is not a good, nor an effective, idea. Instead, it’s another knee-jerk reaction by a government under pressure to prove it’s prioritizing the safety of women and children (ahead of the elections, of course). And as such, it won’t actually do much to improve safety of women and children.

For one, the basic premise of a sex offenders’ database is that convicted offenders are more likely to commit the same crime again. Leah Verghese, a researcher at Amnesty International India, points out that data in India proves this isn’t the case here. Data collected by the NCRB shows that the percent of recidivism by convicted offenders was only 6.4% in 2016. The rate of recidivism specifically for sexual offences is unknown because the NCRB does not have aggregated data — which they stated in response to an RTI filed by Amnesty International India. So, one would wonder, how does a government decide to put money, time, and resources into creating this registry, when there is hardly any research or data proving whether it will be effective?

The database seems to be responding to widely publicized cases of rape in which the perpetrators were unknown to the victims — but the numbers tell a different story. NCRB data shows that in 2016, 94.6% of rape cases reported by women and children named family members and acquaintances as the assaulters. The lack of national laws to protect victims and witnesses means that many cases go unreported, or victims turn hostile and forgo reporting for fear of turning in people known to them. Offenders’ inclusion in a national registry might further dissuade victims — especially children — from speaking up.

The Ministry of Home Affairs’ grouping of offenders into the three classes of low, moderate, or high danger leaves a lot of vagueness that could facilitate misuse. “Low danger” offenders include people charged with “Technical Rape,” which may also include consensual sex with a girl who is under 18 — a criminal charge that can be filed by the girl’s parents and is blind to the idea of teenage consent. Offenders who may pose a “moderate danger,” and would stay on the registry for 25 years, include people charged under sections 67 and 67A of the Information Technology Act, which criminalizes “obscene” material. Of course, the vague definition of what constitutes obscenity falls to the judgment of law enforcement officials, and is frequently used to curtail political sentiments and digital freedoms.

That offenders like the 19-year-old who made “abusive comments” about our Prime Minister would be treated the same as an adult who sexually assaults someone, is, perhaps, something the Ministry of Home Affairs might have considered before compiling this database.

The policy also leaves open the question of when a person’s name would be added to the list. Considering the backlog in our criminal justice system and the time it takes for cases to reach courts, the verdict against an offender might only arrive 15 to 20 years after the fact.

Justice in India is a convoluted process. Which means that vigilante violence is often the quickest way to retribution. Attacks on the basis of inter-caste or inter-religious relationships are not uncommon, and mob lynching based on rumors (or WhatsApp messages) are rife. Any kind of data breach, or even hearsay of someone’s name on this registry, could engender the kind of frenzied mob violence that the justice system is in place to prevent.

A statement from the Home Ministry said that the database will not compromise any individual’s privacy, but this doesn’t feel very reassuring considering the addition of offenders’ Aadhaar card details. Putting the question of state surveillance aside, data breaches within the Aadhaar system are not uncommon, with reports of agents selling access to data for Rs. 500. That the data of 1.2 billion people can be bought is scary enough, but if there are leaks that link people’s information to the sex offenders’ registry, the consequences could be deadly.

The creation of this policy seems to be treating the wrong symptoms, rather than getting to the root of the disease. The rape cases covered extensively in the media do not represent the quiet, ubiquitous nature of sexual violence that women and children (of both genders) face in India. 99.1% of cases are unreported, according to the National Family Health Survey. Instead of addressing this problem, instead of creating measures that would encourage victims to come forward, instead of training law enforcement and medical professionals to handle cases with sensitivity, instead of enforcing the laws already in place and creating protective measures for people who do report abuse — the government is choosing to prioritize this problematic policy. And that means taking money, time, and resources away from initiatives that might actually benefit survivors — and prevent future abuse.

Nadia Nooreyezdan is The Swaddle's culture editor. Since graduating from Columbia Journalism School, she spends her time thinking about aliens, cyborgs, and social justice sci-fi. She's also working on a memoir about her family's journey from Iran to India.

Related

The Dehradun Boarding School Gang Rape Is Outrageous. It’s Also Part of a Trend.