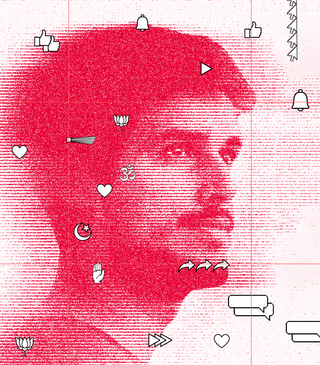

The People's YouTuber

How 29-year-old Dhruv Rathee became one of India’s loudest dissenting voices.

I

“I felt that if I stayed silent, nothing would happen. If not me, then who?”

Dhruv Rathee uploaded his first YouTube video 10 years ago when he was 19, titled “Crazy German Water Park: Filmed on iPhone 5s.” There is no dialogue or script; he films himself going down large waterslides, performing underwater somersaults and backflips into a large pool.

His most recent video – his 649th – is titled: “Is India the Vishwaguru? PM Modi Vs PM Nehru Report Card.” In the two days since it went live, it has just over 11.5 million views. “I think I should have thought twice about using my real name and face in public [to go political] because it can have a lot of repercussions… ”

But perhaps it was the fact that he continued using his real identity while talking about highly political topics that led to an explosion of his channel. In the last two months alone, he says it grew by five million subscribers. This also fetched him international attention as the one of the loudest voices critiquing the Modi government.

Today, he has 20 million subscribers on YouTube. “I don’t think much about numbers. But sure, it would be good to reach almost every person in India,” he says. All his videos go viral, and politicians from opposition parties routinely share his content. Earlier this year, Delhi’s Chief Minister, Arvind Kejriwal, was even hit with a defamation case just for sharing one of Rathee’s videos.

Over the course of our hour-long call, Rathee keeps his camera off and his responses clipped. He’s not exactly curt; he’s just no-nonsense, careful. One might take this to be cunning. But it’s his voice – calm, measured, and sincere – that indicates a mild-mannered demeanor. He appears reserved and, funnily enough – despite millions of subscribers, falling into the political crossfire, and making powerful friends and enemies in high places – still not used to the attention.

Though he politely keeps me at a distance, there are a few moments when he nearly lets the drawbridge down. One of those is when we talk about the idea of celebrity, and how many people in his position would start to feel like one. Why doesn’t he? “What’s the point? It’s just annoying,” he says. I think I can hear him smiling. “I see YouTubers with one tenth the amount of followers than me going around in public with bodyguards to attract attention. I find that a waste of time,” he says.

Besides, he adds, “I genuinely enjoy the privacy that I have, where people don’t recognize me on the streets.” I can’t help but think that this sounds exactly like what a celebrity would say. Except, there’s the fact that he’s so conspicuously elusive: absent from high-visibility events like award shows, red carpets, and premiers that star influencers, content creators, even journalists and news anchors usually jostle to get into. “I feel like 90% of those awards are a fraud,” he says, laughing. “Especially these influencer awards, which is a new thing.”

This year’s Disruptor of the Year award was given to another YouTube creator Ranveer Allahbadia, aka Beer Biceps, who received his trophy from the Prime Minister himself. Despite Allahbadia’s content being the polar opposite of Rathee’s, the former once called himself a friend of Rathee’s on record. Since then, however, Rathee has publicly accused the recipients of these awards of worshiping at the Prime Minister’s feet.

“Red carpet events probably don’t want such outspoken people [like me],” he continues. “They want people who pretend to be popular but stay silent and not speak much.”

The main issues Rathee's team is trying to tackle in this election, he says, is preserving “India’s essence, our democracy, and our Constitution.”

Dhruv Rathee was born in Rohtak, Haryana, and per publicly available information, comes from the dominant Jat caste. He went to a CBSE school in Delhi, then pursued an engineering degree in Germany when he was 17. On camera, he looks like the boy next door: unassuming, fair-skinned, symmetrical features, a little bit of facial hair. His sartorial choices are indistinct and consistent: he sticks to monochrome t-shirts with no visible branding on them. He also vlogs, and documents his leisure activities: he hikes, goes skydiving, and makes couple reels with his German partner, Juli. The two vlogged their wedding last year – two ceremonies, one Hindu, one Christian. She’s beautiful in an aristocratic, fairytale sort of way; together, they make a handsome pair, appearing to live a fairytale life. Some might look to him as the aspirational ideal for a “middle-class” Indian man, settled abroad, married to a foreigner, making good money on a tech platform. He’s an adarsh balak, as one of his team members puts it. If millions of people listen to his political rhetoric, at least a part of it is arguably because many relate to his persona – and consider themselves a version of him.

What seals the deal for so many of his followers is that he packages all of this – himself – into a brand of “true blue patriotism,” as one of his team members puts it. There’s an anti-establishment zeal powering the ethos of his team: this, they say, will persist no matter who is in power. It’s a sentiment that Dhruv Rathee echoes. Right now, they’re hoping to publish content that will inform voters about the truth about this ruling party. It’s been busier than ever during election season, they say, because all of them are hoping that their work will make a difference in it. The main issues they’re trying to tackle in this election, per Rathee, is preserving “India’s essence, our democracy, and our Constitution.”

Rathee’s videos are all in Hindi – a departure from his English-speaking content-creator peers on the Internet. His goal, he says, is to reach every person who speaks Hindi. And now, he’s expanded beyond YouTube: on WhatsApp, he launched the “Mission 100 Crore” campaign, as a strategy to deploy his viewers to proliferate his videos as counters to IT cell propaganda.

The team is careful not to be seen openly siding with any political party, and says they’ve taken up the mantle that the opposition parties dropped. Their guiding principle, they say, is “speaking against power,” irrespective of which party is in it. And so, for the purposes of this election, they all worked extra hard “to make sure we survive when the world ends.” Rathee’s latest videos on India being a dictatorship – arguably his most political – received overwhelming support.

For his part, Rathee says he doesn’t endorse any party because “who knows how they will behave in the future?” It’s clear who he stands against, but not whom, or what, he stands for. And yet, he’s become the unwitting face of the opposition at large.

We talk about the chatter that he might have been responsible for the opposition parties – particularly the Congress and the AAP – improving their electoral strategy. “Yeah,” he says. “Some people do think that. Who knows, maybe?” he sounds like he’s smiling again. Whether out of humility or something else, I can’t tell. On politicians sharing his videos, he says “it shows the influence that I have. And I see it as a good thing.”

No one quite knows how to place Rathee in the current media and political landscape. Is he a content creator, an influencer, a political campaigner, a journalist, or all of the above? Rathee himself prefers a carefully chosen designation: “YouTube educator.”

II

“Sharmaji ka beta” is a bogeyman created by “middle-class” parents as an aspirational ideal for their kids. That’s arguably who Rathee is and what he tries to teach people to be: successful, pragmatic, smart, informed.

As an influencer, Rathee started out like most other techie content creators: covering lifestyle, science, finance, and infotainment. He has a show on Netflix in which he breaks down TV and popular culture, a podcast on Spotify, and sponsored travel vlogs. Balram Vishwakarma, the admin of the popular Instagram page “andheriwestshitposting” knew Rathee in his early days, back when he wasn’t the politically awakened firebrand he is today. Back then, he was simply a YouTuber – one of several – who made “relatable” and “informative” videos. Those attributes in his content have largely remained, albeit applied to a more political mission now.

Rathee’s role as an educator extends beyond politics. On his website, the first thing you can see are the words “LEARN WHAT SCHOOL DOESN’T TEACH YOU” emblazoned across the homepage: at “Dhruv Rathee Academy,” he offers self-improvement courses on time-management and productivity, becoming a YouTube content creator, and mastering ChatGPT. Many of his videos explain how to do research, what a logical fallacy is, and even guide viewers through processes like how to book airline tickets. Rathee’s more “apolitical” content like this seems to give him the air and the authority to have a trusted position on politics.

The admin of the page “Liberal Activist” on Instagram, who prefers the pseudonym “Ralph,” calls Dhruv Rathee the “virtual opposition.” He trusts Rathee to be informed and trustworthy. When Ralph, who is from Jammu & Kashmir, logged back online after more than a year of an Internet shutdown in his state, he found that Rathee was one of the only big voices speaking about what was happening in the state amid the communications blackout. He was also charmed by Rathee’s persona. “When you think of politics, you always think of aggression,” he says, but Rathee is “soft-spoken.” “Whenever he introduces himself, he says ‘Namaskar doston.’”

The consistency in his persona – rational, calm, level-headed – makes him more appealing and accessible than those who “wear their ideology on their sleeve,” especially in such a polarized atmosphere, says Bollywood actor Swara Bhasker.

According to Andre Borges, a similar content-creator from the original Buzzfeed India cohort, Rathee can best be described as a “de-influencer” – he uses evidence and logic to dispel hagiographic myths around political leaders like the Prime Minister, and is often a young demographic’s gateway into thinking critically about politics. “Young people want to know more,” Borges says.

“Dhruv Rathee feels genuine,” agrees Lakhshya, 25, an IIM Indore graduate. Rathee was his entry-point into becoming politically engaged and aware, even in an apolitical campus like an IIM. His videos are digestible, easy; a good beginner’s guide, he says. He sends them to friends who are looking to understand issues but don’t have a trusted source: for many in this cohort, Rathee is the needle-mover spurring apolitical students into progressive leanings.

“Leftists are unreasonably rude… They’ll throw a book at you,” quips Vishwakarma, speaking to why Rathee has been able to tap into such a large audience. Before Rathee, there was no blueprint for how to make a largely apolitical, urban-educated cohort of Internet users stay engaged with political content. The consistency in his persona – rational, calm, level-headed – makes him more appealing and accessible than those who “wear their ideology on their sleeve,” especially in such a polarized atmosphere, says Bollywood actor Swara Bhasker, whose name is frequently invoked alongside Rathee’s. She identifies herself as the type who does wear her ideology on her sleeve; and as much more of a leftist than Rathee. But at the end of the day the political distinctions between Rathee and Bhasker are immaterial in the larger scheme of things. The right, she says, paints all dissenters – like Rathee, herself, and everyone critical of the government – as “anti-national.” This makes Rathee’s work valuable, offering a counter-narrative that encompasses many different interests.

To most of his viewers, what matters most is his heart being in the right place. He comes across as principled: on his website, he states his ethical criteria for working with brands, vowing to stay away from gambling, alcohol, tobacco, or other harmful companies. According to his team and acquaintances, at present he also doesn’t work with “Sanghi” companies. In that way, he’s markedly different from those who helm the right-wing, pro-government influencer ecosystem. A large number of big accounts today are a part of this cohort, I say—

“—and the rest of them are too concerned with how it would affect them personally and professionally,” he interjects. “So they want to play it safe.”

Remembering his recent statements on the pitfalls of being apolitical, I ask: do those other creators he’s referring to disappoint him?

“It’s kind of expected. You can’t expect everyone to give up their careers and everything they did in their lives for one political opinion. I wouldn’t necessarily blame them. I would blame the system that’s forcing them to keep quiet.”

Since Dhruv Rathee took his more decisively political turn, several creators have followed in his footsteps, making informative explainer videos to contextualize politics and attempting to mobilize public opinion for or against a particular side. But Rathee remains the largest of such creators in terms of sheer reach – making him a singular larger-than-life persona.

Unlike a typical influencer, Rathee is closed off about his personal life, save for the few vlogs in which he gives followers a glimpse of his outdoorsy activities. He is never the story, Vishwakarma says. Like a journalist, one might say.

Others who do similar work describe him as akin to comedian-newscasters like John Oliver and John Stewart – not strictly a journalist but rigorous and ideologically focused.

A freelance designer who once worked with Rathee, once joked to Rathee about why he wouldn’t do a meet and greet with his fans like other influencers do. “Do you think a meet-up is possible in this government?” he allegedly replied. Indeed, influencers are not the cohort that Rathee associates himself with. When Rathee visited India earlier this year, he publicly met with a man who invites the most comparison with Rathee’s own work: the former primetime Hindi-media star journalist, Ravish Kumar.

.png?w=320&h=320&auto=format)

III

“You can see me as sort of like what the 9PM news anchor does, but in a more dignified and reputable way,” Rathee says.

Earlier, Ravish Kumar was the final voice on 9PM network television to counter what both he and Rathee openly refer to as the “Godi media” in their videos. Rathee almost fashions himself after Kumar: his younger, faster, unofficial protegé.

“Dhruv Rathee is the result of an asymmetry in the news media landscape, geared towards the right wing. On-air reportage has disappeared and given way to opinion-based news, which is cheaper to produce,” says Faiz Ullah, a media studies professor from TISS.

N. Kalyan Raman, a literary translator who has taught New Media journalism in a prominent J-School, explains to me that Rathee’s format builds upon traditional journalistic styles, such as investigative journalism, “attack” journalism, and “crusader” journalism. He calls Rathee’s style “evangelist.” “He curates work done by other journalists, but he delivers it in a blitz mode, accompanied by lightning and thunder. He uses the visual medium effectively… and that is why he is successful.” Conventional journalism was never meant to be a tool for mass mobilization, but Rathee’s work aims to be. “An evangelist promotes god and religion, this guy seems to promote the interests of the people,” Raman says.

The evangelical style, Raman further explains, isn’t new: it was pioneered long ago by news anchors like Navika Kumar, Arnab Goswami, and Sudhir Chaudhry, all of whom have been accused of becoming spokespersons of the ruling party and the government. To his viewers, Rathee, who uses reason and facts, feels like the first of his kind on “the other” side – “in a good way.”

“Whether it is airline tickets or the establishment, he is free and he is talking his mind… he isn’t batting for anybody."

Another factor in explaining the rise of Rathee's style of media is its similarity with the ruling party’s communication style and its subsequent media influence. Since the early 2000s, explains Pamela Philipose, a journalist and media researcher, the BJP leveraged the power of visual media to disseminate propaganda. In Gujarat, especially, "Modi understood the power of digital media in being a direct means of communication with people,” she explains. “He now no longer had to engage with the often critical mainstream media. Over time he was able to tame and capture mainstream media through a variety of means, including building ties with the proprietors of these media houses."

Once the mainstream collapsed, the space for opposition was virtually non-existent. “Dhruv Rathee saw an opportunity in that vacuum,” says Philipose. “But he had an additional advantage – he was operating out of the country and (now) also has enviable national and international visibility,” she adds. Plus, “it made excellent business sense as well. As the money flowed in, it allowed him to talk even more, even louder."

In the last few years, journalists have enjoyed fewer protections than ever. In the consequent atmosphere of reduced security and lower wages, journalists have become less free to do their job. In addition, editors, bound by the interests of owners, led to diluted reportage. With Dhruv Rathee working independently today – outside the wage or contract system – one gets the sense that “whether it is airline tickets or the establishment, he is free and he is talking his mind… he isn’t batting for anybody,” as Sridhar V, veteran journalist at Frontline and one of its former Associate Editors, puts it.

Nobody can quite agree, however, on whether to call Rathee a journalist, or whether he even represents something new in the media establishment.

“What are the prerequisites? A journalism course isn’t… journalism can be learnt,” says Ragamalika Karthikeyan, a journalist and communications professional. After all, Rathee communicates with many people and challenges power – this is what journalists should do. By this definition, Arnab Goswami would not be called a journalist, but Rathee would. Besides, the line between content and journalism is thinning, considering that breaking news, explainers, and opinion pieces can be found across purveyors of both. “What Dhruv Rathee is doing is important… people's attention is divided between several sources including entertainment media, but that doesn't mean everyone is in direct competition with each other,” Karthikeyan says.

Traditional journalists, moreover, tend to be too stuck on their training to be concerned with reach – but Rathee’s influencer background gives him a head start over that obstacle. In a way, Dhruv Rathee is less a journalist himself and more a bridge between media houses and people, says Sandhya Ramesh, a science journalist. She says that Rathee’s recent video on climate change, for instance, could improve media literacy around the topic.

“He gets his credibility from doing what journalists do – he’s a star anchor. He’s drawing from the old model and building something new,” Philipose says. Unlike the Nehruvian era which discouraged media monopolies, today’s landscape is ruled by just those. That Dhruv Rathee is a single person resembling a media institution is a product of the times.

“A story doesn’t belong to a journalist… Dhruv Rathee makes stories travel,” explains Dhanya Rajendran, the founding editor-in-chief of The News Minute. In that sense, he isn’t competing with publications per se – media houses perturbed by his presence can view it as a challenge and strategize on how they can reach bigger audiences, she notes. And in an environment where “we seriously lack media literacy,” as Rajendran puts it, Rathee has an impact because he often presents a well- researched viewpoint.

“In the larger sense of the media landscape, let this game be played out. But don’t call it journalism. It is fact-based propaganda in one direction.”

On the flipside of this favorable assessment of Rathee’s work and methods, however, is the fact that “the difference between media and journalism is huge, and people never actually sit and think about what this difference is,” according to Hartosh Singh Bal, the executive editor of The Caravan. “No longer is there a possibility of large mass media that is journalistic.”

Though many claim Rathee to be the journalistic answer to Arnab Goswami’s rhetoric on the opposition side, as it were, Bal says that the “sideism” framework tends to lump those who are critical of the BJP (including journalists), and those who work for the Congress and Aam Aadmi Party together. In today’s ecosystem, the distinction between a journalist and a party mobilizer is disappearing. “In the larger sense of the media landscape, let this game be played out. But don’t call it journalism. It is fact-based propaganda in one direction.”

The more popular such formats are, the less viable journalism is, Bal continues. All aggregators of news use a substratum of ground reportage. Beyond its political impact, such a model of disseminating information is such that “all these eyeballs are not translating into money on the ground for reportage," explains Bal. Merely crediting media houses, then, is not enough: the curatorial function that Rathee serves is similar to that of Google. It benefits the platform, not the source.

There’s also the issue of transparency. “While one must appreciate the courage and commitment of many of these private individuals, it is something of a concern that they operate within a code and process of their own making, without the structural checks and balances of a news organization,” says Usha Raman, a media studies professor at the University of Hyderabad.

In a recent video, Dhruv Rathee attempted to discredit a woman’s claim that she was harassed in Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s residence. Swati Maliwal, the woman in question, later went on record to say that Rathee’s video led to her receiving rape and death threats.

“Journalistically, I couldn’t ever imagine any organization putting out a video like that,” Bal said. “But this violation of what would be journalistic norms has already happened because of the huge space of media that exists on the right wing.” In that way, Rathee is not the beginning, but the culmination of an ongoing shift in Indian media. Plus, with Rathee, there is no complete public knowledge as to who comprises Rathee’s team, who edits or fact-checks his content, and thus, nobody who is answerable to the public in any meaningful way.

I learnt that the Dhruv Rathee phenomenon is supported by a team of 10-15 – nobody confirms the exact number – of researchers, video editors, creative producers and associates, and a few rotating freelancers. His core team claims that they’re diverse in terms of religion and caste, but Rathee admits the gender ratio is skewed toward men. Most of them are anonymous and not publicly credited.

Rathee doesn’t live in India but his team members do. He insists on their anonymity in order to protect them, as the government could target them as a way of going after him.

As one of the most prominent people in Indian media today, Rathee has a heavy responsibility. For a public who isn’t concerned with or interested in his exact designation, he looks like someone who ought to carry the length and breadth of topics that a news organization might, but he’s really just one person whose channel represents his own, implicit political leanings – and biases.

For all the work against bigotry that Rathee is exalted for, one of the biggest criticisms of his approach is that he is largely silent – even agnostic – on caste. He occupies the mantle of an educator, especially during a crucial election. But as journalist Greeshma Kuthar asks of all such YouTube educators: “how conscious of social realities are they?”

IV

Rathee’s fledgling interest in politics began in 2011, with the anti-corruption movement led by Anna Hazare. Anna Hazare was the neo-Gandhian figure who brought hunger strikes and people’s marches into the ethos of the affluent, upwardly mobile class (and castes) of Indians.

The anti-corruption movement, for instance, is widely remembered as a moment when the conservative “middle-class” (who is actually in the top-percentile of earners and largely upper caste) found a political voice to express dissatisfaction with the Congress establishment. This movement, however, is what indirectly paved the way for the BJP’s rise to an absolute majority in Parliament in 2014. In his early days of content creation, Rathee’s videos weren’t political, let alone critical of the ruling party. He says that, in 2014, “I had a lot of hopes from Modi when he became Prime Minister, and I believed in him. But very quickly I realized he’s not what he seems.”

Most of his political videos, since then, have criticized the government that he once felt hopeful about. The most recent ones have done so with the intent to sway voters against this party. Not everyone, however, is convinced about the strategy he employs to do so.

“I feel it is important to reclaim what our culture used to be – before this government hijacked it.”

Take the fact that Rathee is best known for his water-tight citations in his videos. In his recent and most political video that examined the Prime Minister’s “dictator mentality,” he cites mainstream and independent digital media organizations known for their factual rigor, but also websites like Osho News to discredit the PM’s narrative of his life story. Then, he invokes the figure of the Hindu god Ram and descriptions of “Ramrajya” (Ram’s kingdom) as written in the text, and makes a case for why Modi’s India – which weaponizes Ram – is antithetical to this “originally” peaceful mythology.

For all his invocations of Ram, Rathee describes himself as a “Hindu atheist.” I ask him to define that. “I grew up in a Hindu household, practiced a lot of traditions that Hindu families do, but don’t believe in God,” he says.

But it’s Ram, the God, that he engages with the most in a bid to emotionally resonate with potential fence-sitting voters. In a recent controversial short posted on Ram Navami this year – an excerpt from the longer video from 2023 on the “truth” about the Ramayana – he cited Ram as a positive example of masculinity. “This is something that I’m getting used to. Indians care a lot about their festivals,” he says. He never used to post during Diwali or Holi – but he does now because people seem to want it. It received backlash, because although he built his political viewership on a platform of secular liberalism, his content decisions reflect otherwise. This short, for instance, was close to the occasion of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary; a day which he did not commemorate the same way as he did the Hindu festival.

When I asked him why he feels he needs to defend Ram specifically during elections, he says “I feel it is important to reclaim what our culture used to be – before this government hijacked it.”

However, academics point out that electoral politics in India have always been about caste. As the historian Christophe Jaffrelot points out in his book Modi’s India, Hindutva ideology’s preoccupation with Ram, which precedes this government, is just one way in which the BJP has mobilized voters along caste lines.

His critics accuse Rathee of being politically naive. As Lokesh, an anti-caste writer and the nephew of Orissa’s first Dalit novelist, Akhila Naik, puts it, “BJP has a strong Hindutva ideology. Its opposite can only be anti-caste, Ambedkarite. Only that is strong enough.” What Rathee is really doing, Lokesh says, is endorsing soft-Hindutva, which only weakens his stance against the BJP.

Instead of questioning how Hindu mythology and scripture have upheld the caste system, Rathee uses them as a call to action to fellow-Hindus to “reclaim” Ram. In the same video, for instance, he refers to “humara Hindu dharm” – “our Hindu duty.” In an older video about the “truth of Ramayan,” Rathee once again cites a passage in the Ramayan which describes Ram’s kingdom as one in which the four castes (varnas) – Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra – did “their” work in peace. This is easily overlooked, unless a viewer already understands that this system was a historically hierarchical one, in which people were assigned labour – educators (Brahmins), warriors (Kshatriyas), merchants (Vaishyas) and farmers/manual laborers (Shudras) – by birth.

“So far in print and digital media, the media mindset did not allow any Shudra [like Rathee] to emerge as a powerful shaker [of the establishment].”

In the same video, Rathee also quotes the Manusmriti’s definition of “duty” – patience, restraint, increasing knowledge, among others. The Manusmriti, however, is a widely condemned text that is considered to violently uphold the caste system – a book that Dr. B.R. Ambedkar famously burned.

Rathee says that there is no right way to approach this. “If [the critics] feel so they are free to try, but I feel the other way,” he says. “Ram is part of our culture and tradition. I just cannot let it be hijacked by political forces who want to exploit it and use it for their benefit,” Rathee tells me. His personal attachment to the figure of Ram remains limited to: “I watched the animated show while growing up… I feel it is our culture that is being distorted.”

“When you say our culture…” I venture.

“Me and whoever believes in it,” he replies, noncommittally.

Sometimes, these gaps in his focus are more explicit. In his infamous Ram Navami video, in which he insisted on separating “Ram” from “Nathuram [Godse],” he used a casteist slur to describe Hindu nationalists.

“I did not know that it was a casteist term,” he told me when I asked him about it. “I still don’t feel that it is, but other people do, so after that I stopped using it. That was the last time I used it,” he says.

It might be that Rathee’s audience simply doesn’t care about caste. “If he starts talking about casteism, his target group might stop watching his videos,” Vishwakarma says. “Even OBCs [Other Backward Castes] shy away from discussing caste. I’m saying this as a guy coming from an OBC background.” Just who is Rathee’s target group, then? “Aspirational, liberal, Aamir Khan’s Satyamev Jayate-liking wale,” he says.

I asked a member of his team about the critique that they don’t pay enough attention to caste. “No, he does. He made four videos… how Ambedkar was against caste and… stuff like that. We have made stuff like that.”

As for Rathee himself: “I think I’ve made quite a few videos against casteism and even classism for that matter. But of course, I have to see what topics to prioritize. There’s limited time.”

If Rathee as a media personality is a product of the vacuum that preceded him, Rathee as a political figure is a product of caste-based politics that preceded him.

It’s also caste that explains Rathee’s own rise to such political and media significance during the elections. The sociologist Ravikant Kisana explains that since Independence, state power has always been a tussle between the caste elites and the coalitions of lowered castes who came together to challenge it. In the current moment, economic stagnation has led to a young generation of caste-Hindus divesting from their parents’ faith in the BJP and looking to Rathee as “their boxer.” As Rathee’s Ambedkarite critics point out, then, Rathee is mainly speaking to them by appealing to their Hindu faith – without a clear understanding of how their caste positionality was responsible for the current government in the first place.

Rathee’s own caste positionality provides hints as to how much more of an impact he could have had as a media personality – perhaps even during this election – and how he’s held back by the gaps in his understanding. “Dhruv Rathee is an interesting person,” says anti-caste scholar Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd. “Because the caste background of most YouTubers and anchors is Dwija [Brahmin/Kshatriya]” – whether it is right-wing figures like Arnab Goswami or liberal ones like Rajdeep Sardesai or Ravish Kumar, he points out. In contrast, Rathee is a Jat, which is a Shudra caste. “So far in print and digital media, the media mindset did not allow any Shudra [like Rathee] to emerge as a powerful shaker [of the establishment].”

The details of his personal beliefs and his caste positionality speak to broader questions about the identity formations at the heart of the Indian polis and politics. Despite his position as an outlier to the upper-caste media establishment, Rathee assimilates as one of them. Shepherd, who is unsurprised by this, points out that the Jat community from Haryana has never seriously aligned itself with the Phule-Ambedkarite cause. “They always wanted to be Brahmin-Kshatriya…” And thus, “Dhruv Rathee’s [caste] consciousness has not grown.”

All this makes his coverage of the election – and the issues he wants to draw people’s attention to – selective. As Ritu, an anti-caste writer points out, it shows in the form of inconsistencies in what he chooses to cover: he tackled Delhi’s upper caste CM’s arrest, but ignored Jharkhand’s tribal CM’s arrest. He praised figures like previous BJP Prime Minister Vajpayee, but overlooks anti-caste political figures like Chandrasekhar Azad. Rathee’s immunity to serious harm as a dominant caste man gives him an opportunity to speak up on behalf of those without his power and resources – but it’s a position he doesn’t use to build solidarity with SC/ST/OBC audiences. Instead, he identifies himself as a Hindu, and exhorts viewers to protect “our” religion from being hijacked.

If Rathee as a media personality is a product of the vacuum that preceded him, Rathee as a political figure is a product of caste-based politics that preceded him. While he understands the former, he arguably doesn’t recognize the latter – making his positioning as a news source in this election year complicated.

.png?w=320&h=320&auto=format)

V

Despite word on the street whispering about a government change, the few exit polls that have trickled in predict a majority for the BJP. I texted Rathee to ask him how he felt about this, but he didn’t want to comment.

He is one individual: 29 years old, with a lot to learn. He put himself in the public eye during the years when many people begin to form their political opinions and develop their ideological consciousness. Unlike most people’s, however, Rathee’s evolution has been public: over the last few years, he was heavily criticized for his positions debating the legality of migrants, applauding the abrogation of Article 370, praising right-wing political figures like Vajpayee, and other stances he used to take as a “centrist.” Some of these opinions have since changed, as most people’s inevitably do. If his record on changing his views is anything to go by, this is not where his evolution ends. But if millions saw him as the answer despite his greenness – maybe even because of it – it’s because in their eyes, there was nobody else.

“It's important that he continues to raise the issues he does and to do it with the same level of energy – but yes, it is dangerous if he becomes the ONLY such voice,” says Usha Raman.

“People have started seeing him as a future political figure, someone who will change the political narrative of India,” says Ralph. They think that if the Congress improved or faced any kind of pressure from the youth on their weak leadership, it was because of Rathee’s influence. Indeed, as the “virtual opposition,” Rathee was the meeting point of several differing ideologues throwing their weight behind him. He was locus of a virtual, liberal-left coalition – many of whom vehemently disagreed on the stakes at hand, but all of whom recognized a common interest in amplifying dissent and criticism.

Rathee may have thus played a role in simply reigniting a culture of critical speech. Even if we don’t see any electoral significance this time, “It’s important for these ideas to reach people and seed debate,” says Sujith Reddy, a political consultant and founder of LEAD. “Debates, once seeded, will sooner or later play a critical role in the collective consensus of the electorate.” But it remains to be seen if Rathee is the harbinger of a new form of political engagement, or if it’ll fizzle out with him. Content creators in his niche think he’s reached his saturation point. Others feel he might evolve into something else entirely. With the messianic undertones to the way people speak about him, it’s anyone’s guess what that might look like.

“Regardless of whatever impact Dhruv has, the reason Dhruv is important is because people who should have known and done much more didn’t do their job,” says Anupam Guha, assistant professor at the Center For Policy Studies in IIT Bombay. “The media has criminally failed in speaking truth to power… political parties which claim they are progressive and have lakhs of cadres and academics have not even been able to engage the urban aspirational youth who Dhruv caters to,” Guha adds.

The question of whether he’s going to make a difference in the election, therefore, is irrelevant, insofar as we’re in a vacuum of oppositional voices. And the question of whether Rathee is impactful is better answered with another question: “Is anybody else doing a better job?” And further, Guha adds, it would have been a relevant question if we had been "operating in a reality where the media, academia, and political broadcasts worked themselves to be accessible to the depoliticised masses. They haven’t. So Dhruv does.”

“The only thing that can happen at this point is they try to ban or block me because of how outspoken I have been."

I finish the interview with Rathee a little over the time he said he could allot for me. As a final question, I ask if there’s a specific reason he wanted to keep his camera off. Was he being careful? After all, he began the interview, asking me to watch his YouTube Q&A video on his personal life (“because that was very carefully selected”), with this caveat: “I will only tell you what I want to be public.” But now, he cuts me off – “No no! It’s just because I’m walking outside and my phone was in my pocket. Here, I’ll show you.”

He switches his camera on for a brief moment. He’s wearing his signature gray T-shirt, wired earphones plugged in. He’s surrounded by verdant greenery. He flashes a bright, toothy smile, showing me he is real. Then, he switches it off.

Something about this gesture warms me to him. It feels innocent. After living in his digital world and hearing so much about his persona, there is something about the anticlimactic frankness that brings him back down to Earth. The smile is hopeful. Perhaps it represents the privilege and comfort of his insulation from the insidious politics here in his home country. Perhaps it’s just who he is: optimistic, in the face of everything, with a lot to learn and the energy to try everything he can.

But his own future depends on this election too. “The only thing that can happen at this point is they try to ban or block me because of how outspoken I have been… Better make whatever time and influence I have worthwhile,” he says.

“While I have it.”

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.