India Is In Its 'Yes Chef' Era

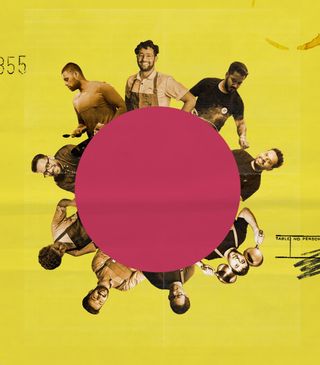

How nine chefs in India created a cult of personality around cooking.

Inside the world of India's culinary elite, and who gets to make it.

The 'Exclusive By Design, Not Attitude' Chef

Known For: Naru Noodle Bar

Bling: “We had Virat Kohli and Anushka Sharma once [and] they did a private buyout."

Alma Mater: Culinary Institute of America: “I think some places [in New York] only took CIA interns because we knew what to do.”

The Bear Inspo: Yes, most definitely, Carmy

Chef Kavan Kutappa of Naru fame has a cult following. There’s internet beefs over reservations, BBMP officials and cops being called to the restaurant, and coders providing Javascript hacks to his booking system, which often crashes – all because a reservation spot at Naru sells out in under a minute.

He pops open a Diet Coke and rolls a cigarette mid-way through the conversation: “You don’t mind, no?” He’s got the quintessential Bangalore drawl but a distinct aesthetic; he’s wearing a minimal Naru merch tee and a basketball cap with chopsticks, boiled eggs, and noodles doodled on it. He says the first time he watched FX’s The Bear, he had to turn it off within 15 minutes. “He mentions my school, CIA (Culinary Institute of America), and my first internship, Eleven Madison Park. Too many memories, and the chaos was triggering.”

“Not the reservation desk for Naru,” proclaims his Instagram bio.

Some would say that a similar chaos plays out to get a seat at Naru – at his table, specifically. “We are exclusive by design, not by attitude, you know?” He set up the unique booking procedure – where you pay before you arrive and redeem against bowls of Ramen – right from when he started the brick-and-mortar ramen spot in Bangalore’s Shantinagar. He gets 8000 unique IP addresses trying to snag a booking; only 150 are successful week on week. He explains why he needs this system: “I ran an eight-seater restaurant. If a group of four decides not to show up, that's half my revenue for that batch, right? And you see how the four-seat cancellation will not affect Bastian.”

“Not the reservation desk for Naru,” proclaims his Instagram bio. Scroll down, and there’s a lot of him in effortlessly breezy poses, a rapid reel montage of him waving at customers, and generally immersed in the hive of activity, himself in the eye of the storm. There’s an old one of just his tatted bicep next to a G&T. He’s the Carmen Berzatto of ramen in India. He says he “could never give into this whole social media thing.” On his profile, however, there’s collaborations with fintech company Cred (a chef's crawl through Bangalore); a campaign ad for Samsung India with actress Samantha Ruth Prabhu; promos for Adidas Sambas and Crocs among pictures of hot bowls of ramen.

So evidently, with Naru, “it's gone from a great place to have ramen, to a place to be seen [at], for your cool factor.” His early experimental pop-ups were Ikebana and Streets of Shibuya inspired. “I had a Japanese bike parked [outside] with a projection of Tokyo’s neon traffic over it.” He later opened Naru, which has now transformed to a 20-seater. Inside, a noodle machine from Japan stands on display. “We make noodles live in front of that space.” He’s drawn to the performativity around ramen because of the “life-changing meals” he had in Japan. He says there’s an enigmatic cult following around ramen.

Still, he insists that “hype is not sustained without a consistent product.” As for having a fan following, he says that a lot of people do come to Naru asking to take a picture with him. “My staff is also tired of it,” but he admits that’s natural, as “this whole story sells also because I'm a local Bangalore boy, doing ramen.”

The 'You Eat Through Your Eyes' Chef

Known for: Culinary pop-ups at his apartment, including one called… Apartment

Culinary Idols: Nasir Armar, Frankie Gaw, and his grandmother who loved to host

Cuisine: “Flavor combinations” that are “contemporary” and “borderless”

His Thing: Having an Ooni pizza oven, being a “pesto purist,” dreaming of turning his house into a bagel shop

Chef Anurag Arora’s aesthetic is very millennial-designer. Over Zoom, in his background is an espresso machine against a Oaxaca-inspired blue and white tiled wall and a neon sign that reads “Flower Bodega” in hot pink. Everyone who is anyone in Bangalore knows him as the foremost apartment pop-up chef: if you can pay 3500 a pop, you get to have the “very intentional,” “very curated,” (very demure?) experience. For that’s what food is about to Anurag: not just tasting, but having taste.

“I remember the last Apartment pop-up had gotten 1041 people on the link for 36 tickets.”

Each of his three wildly diverse pop-up formats don’t just have assistant chefs but also art directors and photographers. It’s a lot of work. The work is equal parts food and equal parts aesthetic, which he says “continues to feel stupid even today.” Despite all the performance around his dishes, he wishes to refrain from calling them “experiences,” because he’s just trying to work on refining his skills. His pop-ups are always sold out. “I remember the last Apartment pop-up had gotten 1041 people on the link for 36 tickets.” He admits that he was surprised by the success too. It’s fine-dining at his house in Indiranagar, Bangalore, one of the city’s most posh locales.

He studied to be a designer and worked as a UI/UX designer, and it shows. Just look at his Instagram: he plates like a Michelin chef. There’s a single pork vindaloo taco on a delicately speckled ceramic dinner plate, highly saturated photographs of handheld juicy burgers dripping with sauce, contrasted with a plate of chicken liver parfait shaped in concentric circles against a bottle of Sauvignon Blanc. He’s conditioned to see it on a plate and admits that the art of making food look fancy is definitely a skill. “If you see my lunch, it’ll still look good” he quips.

His menu has words like crema, shokupan, and béarnaise sauce. It is perhaps the result of cultural immersion in his life as a techie at Uber, which also meant culinary expeditions in Brazil, Mexico and San Francisco. During Covid19, he did the designer-by-night and cook-by-day gig, staging at Rooh, a fine-dining restaurant in San Francisco, also famous for its emphasis on “fusing Indian flavors” with “contemporary tastes.” He describes a ceviche he’s perfected, which includes a sauce that combines 14 “very intentional ingredients.” The word “intentional” comes up a lot.

All of this is because: “If you go to a Michelin star restaurant, they have their plating, decor, vibe and music in place.” So they’re non-negotiable principles that have guided the way he’s curated pop-ups. He’s fastidious about a customized menu, carefully designed and printed for each of the pop-ups, conveying the ambience of the space through delectable photography because “100% I think you eat through your eyes.” The mismatched tableware and “nice linens” are such that “everyone’s base plate will be different, but beautiful for sure.” And while there’s the coziness and warmth of being in a house, “everything around it, from the food to remembering whose water glasses need service, will shout fine-dine,” he says.

Is he a chef or an artist? “I’m a designer and a cook” – not a chef, because it’s a title that requires him to pay his dues, a title he says he’s yet to earn.

The 'Cooking Is Not an Art' Chef

Known For: Americano and Otra

Culinary Idols: The French Laundry’s Thomas Keller and David Kinch; and, of course, his mother and grandmother

Hot Take: “I don't really believe in creativity and I certainly don't believe that cooking is an art.”

Chef Alex Sanchez’s two very swanky and glitzy restaurants in Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda neighborhood are surrounded by colonial and Art Deco architecture, located in quaint alleyways and in a part of the city often romanticized in films and by tourists. “I think people have even written articles about how you can never get a reservation [at Otra],” he says, with a hint of hubris in his voice. He argues that the reservation conundrum is a “great problem to have” for any restaurateur. “What happens when suddenly we have availability? Then will people not want us? Fortunately, we've not gotten to that place yet.”

Who visits his restaurants? “Americano is a ‘neighborhood restaurant,’” – the neighborhood in question being Kala Ghoda, where the going real estate rentals run into the crores. “We wanted to be a place that anyone could go to and you could feel comfortable going in shorts or getting more dressed up.”

"I don't know any major city where you can have an appetizer for $8. I think we're doing all right.”

He says his early childhood was “not the most gastronomical” but also goes on to evocatively describe a life-changing meal in Orvieto, in Southern Umbria, when he was 12. “It was my first time trying mussels, real pasta, and risotto.” Upon returning home to San Francisco, he realized that “there's kind of more to [food] than just boiled spaghetti, hamburgers, Kraft cheese, and chicken nuggets.” And so he entered the service industry after dropping out of college, starting as a dishwasher, and working his way up. He later graduated with top honors from none other than CIA. At this stage of his career, he’s taken on a mentorship role and has many opinions about the green chefs entering the food ecosystem. “Chefs graduating from school today feel that the education they have is worthy enough to land them a sous-chef position, which is just not the case,” he argues. "You can't really have theory without experience."

At his restaurants, the emphasis is on attention to detail, care, experience, and taste; things not on display, he explains. So the price of his food, he argues, is as reasonable as it can be – given the cost of ingredients, rent, overheads, labor. He is quick to draw a parallel for the affordability of his dishes (albeit in dollars). “We're still charging, you know, around 650 rupees a plate for an appetizer, which in dollars is about $8. I don't know any major city where you can have an appetizer for $8. I think we're doing all right.”

He doesn’t like the term “celebrity chef.” “Bill Gates is not a celebrity investor, he's Bill Gates. You don't say Shahrukh Khan is a celebrity actor. Right? He's an actor.” These terminologies, he argues, are a symptom of the fact that society inherently doesn’t respect chefs. He believes that a more apt term to describe a celebrity chef is "industry leader" – someone who builds community, cares for their team, vendors, and suppliers. So is the hype just a flash in the pan then? “Hype is no one’s fault.”

The 'Activist' Chef

Known For: The Bombay Canteen and The Locavore

Social Media Clout: 125K

Chef School: Culinary Institute of America (where else?)

Culinary Idols: “Don’t really have one, but learn from indigenous tribal communities across India.”

Favorite Meal: Grandmother’s duck curry

“Growing up, transforming ingredients into joy was like the superpower that I wanted for myself.” That’s also how Chef Thomas Zacharias promotes his work. He recently did a pop-up of specially curated cocktails that highlighted foraged and wild ingredients, including a bamboo shoot martini. On his Instagram, there’s low-angle shots in slow-mo of TZac donning a deep green apron, pouring cocktails, singing karaoke, and juggling raw ingredients to the Tiktok-famous Tommy Richman’s “Devil Is A Lie.” “I think through my career, or the past 20 years, I've seen the transition from chefs literally being behind kitchen doors to suddenly being the coolest people in the room.”

His story is the same as many other chefs. After graduating from CIA, he worked at three Michelin-starred Le Bernardin, New York, before making his way back to India. “You’re kind of conditioned to believe that Western European food is at a pedestal,” he begins. As these stories go, he went on a sabbatical, a “chef on the road experience” through 36 towns and cities in France, Italy, and Spain for months to “learn about European food.” “But my biggest takeaway was that I had not done the same in India.” So he traveled to 18 places all over India: “What I saw and experienced on this trip completely blew my mind because it was so far removed from the Indian food I had known about.”

“I'm a chef who is an activist. But I feel like a bigot for even saying it.”

Today, he runs The Locavore, where he tries to shed light on niche and native ingredients, while taking it upon himself to fix the food ecosystem, one grassroot effort at a time. His emphasis has thus shifted towards “engaging with farmers, people from various tribal communities, getting into people's homes and kitchens and learning recipes.” He is keenly aware of the plight of farmers and climate change. The paradox of bearing witness to these realities and then coming back to this fancy restaurant that has won all these awards is stark for him.

He believes that he has “played a significant role in the way urban India sees local [Indian] ingredients, and that's 10 years in the making.” And with Locavore, he’s transitioned out of actively working in the kitchen, so he sees himself as “a chef, on borrowed time.” After some deliberation, he vulnerably admits: “I'm a chef who is an activist. But I feel like a bigot for even saying it.”

The 'Bhindi Aloo to Okra Potato' Chef

Known For: Slink & Bardot

Culinary Idols: Heston Blumenthal and Massimo Bottura

Favorite Spots in Bombay: A vada pav street stall in Agar Bazaar (because of the “simplicity and balance of [his] vada pav”) and Americano (because “the food is absolutely spot on”).

Hot Take: “A sad chef doesn’t make a great cook.”

At 29, Chef AliAkbar is one of the youngest of this lot and is doing things differently as the Executive Chef at the swanky Slink & Bardot in Mumbai’s Worli. Earlier this year, as an “ode” to the Kolis (the original settlers of Bombay) he curated a Koli-inspired tasting menu called Taste of Slink: Koliwada Edition. Worli is also the part of town where increased marine pollution and rapid real estate development is pushing younger Kolis out of their Koliwadas to seek alternative modes of income.

AliAkbar came from humble working class beginnings and rose to culinary starhood while stumbling through hotel management school, outdoor catering events, and several abusive kitchens. He grew up in Deolali, a small hill station in Nashik district, a few hours east of Bombay. His father, trained by the Bathiyaras (cooks) at the local masjid, ran a restaurant called Alibaba’s Den. But it was his mum and step-mum who instilled a lot of Bohri and Gujarati staples in his early years, which have since translated into nostalgia-driven fusion dishes on his fine-dining menus. Like good old Aloo Bhindi, “but we can’t call it that, so we call it an Okra Potato.” He explains this dish in a video on his profile: “the potato is made as a light and airy vichyssoise (aka a purée), while the okra is rubbed in sea salt, shucked into ice water and marinated in ponzu, the “Japanese way.”

“We have to create the kind of, like, voodoo around our food.”

Soon, he’s collaborating with Kitchen Raves, to host a “rave” described as “one of a kind experience with electronica and munchies” – all at the behest of his PR team. He also did a 7-part series titled “An Insider Guide to Eating in Bhendi Bazaar” in collaboration with popular food account Mumbai Foodie. In the video he’s walking, eating, and drinking through a food market in a local neighborhood in Bombay, showing an “OG OG place.” “[This video] got more than a million views in less than a week. So, when you're being a little real on Instagram, people appreciate it. And I think that's kind of my vibe.”

He’s got a lot of thoughts about current food trends – specifically, the phenomenon of avocados that’s taken over menus at Indian restaurants, cafes, and streets. “I hate avocados,” he declares but admits with resignation that he was “forced to put it on the menu.” He then goes on to describe the devilled avocado on his menu with techniques and ingredients that include making a cavity, the use of a blowtorch, chilli dust, asparagus, and wasabi. “We have to create a kind of, like, voodoo around our food.” He admits that, in the past, he’s fallen prey to seeking validation from platforms like Instagram, “but now, my life is full of content, so I don't need to create it.”

The 'Nothing Is Authentic' Chef

Known For: Toast & Tonic, The Bear Inspired Pop-ups, and Woodstreet Sauce Co.

The Bear Inspo: Showed up at the Indian Accent lobby to bag a job -- channeling his inner Tina Morerro from The Bear, aka Jeff.

Hot Take: Thinks it's sad that only chefs are seen as sexy. "A carpenter should also be portrayed as a sexy man.”

The anxiety is palpable on Chef Karan’s Instagram. The first video on his profile is blatantly The Bear inspired, as the electric percussion of the show’s soundtrack feverishly cuts to staccato close-up scenes of his set-up. There’s swearing and cussing in Hindi, orders to “stop texting your girlfriend,” the signature blue kitchen tape with “The Bear” Sharpied on it. He introduces someone as his “Fak,” lights a cigarette and plays with a searing hot pan that sends steam into his face. This was the promo video for Karan’s “The Chaos Menu,” which included dishes like “The Michael” and “The Bear.” It’s sexy, drool-worthy content. There’s also the famous poster of the cast (yes, that one), but with Karan, Kavan [Kuttappa], and members of his team masquerading as Carmen Berzatto, Cousin, and Sydney – flanked by Bangalore’s Namma Metro, a davara-tumbler of filter coffee, and crispy benne dosa in the periphery of the promo poster.

“Everybody who has spoken to me in the pursuit of getting their own place, has referred to me as a pop-up expert,” he says.

Pop-ups have been his go-to format since 2022, and he has conceptualized many at The Conservatory in Bangalore. “Everybody who has spoken to me in the pursuit of getting their own place has referred to me as a pop-up expert,” he says. Before he became a pop-up expert, he considered continuing his stint at the Indian Accent outpost in New York as “very tempting.” But as every story of a chef who yearns to make a name for themself goes, he was nagged by this feeling of “why not do it back in my own country?” And so he came back to India, where he joined Toast & Tonic in Bangalore as a demi chef de partie (aka senior chef), because of Chef Manu Chandra’s work with heirloom ingredients “and stuff like that.” Eventually, he went to Spain, as one does, on a culinary sabbatical to learn about the “whole tapas culture,” worked at two Michelin-starred spots – Tickets and Bo.TiC, but he felt out of place in that world. "You're part of this big cog wheel of churning out these perfectly looking mint leaves and perfect looking branches and stuff.”

So he came back to India, where he started experimenting with pop-ups, exploring techniques and ingredients from different cuisines because “I think we've also finally moved past strict rules of taking to boundaries and a particular cuisine. There is no such thing as authentic.” He’s made ham encapsulated in a sherry jelly melon. He’s also done savory achappams with Vitello Tonnato [tuna mayonnaise with chunks of roast buff]. For Karan, it’s all about experimentation: “If soy sauce tastes nice in an Italian dish, I’ll probably season it with that; and the Italian nonnas could be upset, but I like it, and people are getting it so it's a win.”

All of the promos for his pop-ups are imbued with the sense that being a chef is a relatable occupation. “You don’t go to a doctor or see a plumber as much as you eat.” He’s the chef who’s recreated the famous Chaos Menu, but he’s also the chef who “hates socializing outside of the kitchen.” He admits that “there’s no way out of the whole marketing aspect of it.” It helps that The Bear’s Jeremy Allen White, running around in Calvin Klein undies, immortalized the idea of the sexy chef.

The 'OG Bandra-Boy' Chef

Known For: Bandra Born (previously, Salt Water Café)

Degrees of Separation From Noma: 1 (briefly ‘staged’ with René Redzepie of Noma fame)

Hot take: “For me, Mugaritz is church.”

Chef Gresham “Gresh” Fernandes is a Bandra boy, born and raised. He heads Bandra Born, hotly revamped from the minimalist skeletons of the 15-year-old Salt Water Café. Now, there’s a definitive vibe to the space — it's loud, graffitied (rather disruptively), and plastered with layers and layers of stickers. The bar on the second floor is tightly designed – with high-top leather seats and low roofs – mimicking a crowded dive bar. The door to the kitchen is pimped with more stickers that pose extremely pertinent questions like “Where is Bandra Boy?” and “Who is Bandra Boy?” All of which evidently contribute to the grunge aesthetic that’s shaped Bandra Born into this hip neighborhood spot. But why this makeover? “Frankly, it was getting boring for me [at Salt Water Café], and after a point you can’t change the menu. Bombay is also really expensive to live in, and work in.” But the new spot is just as posh and expensive and the reservations are just as hard to get.

Gresh comes from the Old Kantwadi neighborhood of Bandra, in a family commune with many matriarchs and patriarchs: “I don't remember my grandmother ever locking the door of the house.” He romanticizes how the food was always fresh and the kitchen was the focal point of activities. “I grew up with the experience of going to a market [every day]; the fish, bread, and egg guy coming and selling things at home.” Besides eating, they’d share the labor of peeling garlic, cleaning the vegetables or fish.

Over 30 years later, the story he’s crafting at Bandra Born is rather different from his grandmother’s kitchen. The menus come in an array of neon pinks and pastel purple, and typeset in a delicate serif font – it’s all very delectable and elevated. The Brun Maska for example – a quintessential Bombay staple that is hard-crusted bread and butter – is Rs. 175 on his menu. “It's the [XO] butter, not the bread.” The money compounds, he argues, and when cooking in scale “you actually have to take so much yeast to break it down and cook it down to this much to get you that flavor profile.”

“People want experiences, man. It's clickbait.”

Their menu, like many new spots in the city, is made up of small plates – shareable, easy to eat and allows for more experimenting. “In our tasting room session, there are guests who ask for a special cocktail menu that has ingredients like mushroom and rice on it.” He calls all of this a social experiment: having fun with colors in the space, playing loud music and changing up the menu format. “People want experiences, man. It's clickbait.” He explains why he’s taken away basics like salt, pepper, and tabasco from the table, because he believes adjusting a dish to your own taste is “eating for sustenance.” “Now you're eating because the chef has said [you should eat it like this] – so it's all about building experience and taste.”

Gresh argues that there’s nothing wrong with spending on food, especially if you’re earning it. “I know people who would spend Rs. 80,000 or 90,000 on a meal at Alchemist, [because] it's a wonderful life time experience for them. You're doing the spending on yourself.” And as the chef of Bandra Born, he wants to give his patrons just that.

He draws inspiration from spaces outside the culinary industry, like Thomas Deininger, Banksy, and techno musicians like Luigi Tozzi and Dubfire. He notes how all the big chefs (like René Redzepie and Thomas Frebel) “are creative not because they're spending 24 hours in the kitchen. Massimo is an art and a jazz collector.” Though Gresh has a small community of ardent followers, he has also jumped into the PR circus with collabs, inter-city takeovers, and promo videos – while wearing a shirt that reads “Shut Up and Cook” and shouting, “fuck this should’ve been done, we can’t wait, this has to go [on the pass].”

The 'Destination' Chef

Known For: Naar, Himachal Pradesh

Degrees of Separation From Noma: 1 (briefly staged with, none other than, René Redzepie)

Chef School: “Got baptized into the culinary world” at, you guessed it, the Culinary Institute of America.

Price Point: 15 courses, Rs. 6500 (plus taxes)

A glossy profile in The New York Times places Chef Prateek next to legendary chefs like René Redzepie, fitting them within the archetype of “romantic, and even heroic figures,” because of their philosophy around foraging for food. Prateek talks about the fire – naar in Kashmiri – that keeps him going at his new destination restaurant in the hill town of Kasauli, Himachal Pradesh. Being forced to cook Italian and French food in Indian hotels was “killing his passion,” so he left the country, collected star power, and came back with a “desire to put India on the map.” Naar is tucked inside a pine forest away from the city, where he says “the sound of the breeze resembles the sound of a stream because it passes through pine trees.” It’s all part of the “elevated” experience at Naar, his fine-dining restaurant.

“We're using the same alphabet, but we're creating a new language.”

The metaphors of roots, belonging, and nature feature heavily in the curated narrative of Naar. Perhaps because it’s run by a chef with his own story about roots and belonging. As a Kashmiri Pandit, his family fled Baramulla, Kashmir, in the 90s to their new home in Delhi. Growing up, he primarily ate traditional Kashmiri food, including dried fish, despite having access to fresh fish. On birthdays, a meal of Kashmiri recipes would be followed by the family sharing stories, both personal and historical. These early ideas carried over to Naar, where it’s all about “understanding the ecosystem, the microclimates, and creating an experience around food.” He clarifies how foraging for ingredients and depending on the forest is not new: “we're using the same alphabet, but we're creating a new language.”

But who’s visiting Naar in this remote place that’s 45 minutes away from Kasauli Market? “A month before we opened the restaurant, we had 300 emails [to book a table] and our phones were constantly working.” And it’s not just the urban elite; he also has diners from Tier 2 cities. He believes that the consumer is well aware of what they want. They are “traveling the world and are exposed to good food in a bad world.”

Evidently, he loves the world of fine-dining, a lot: “From the level of discipline, to the sense of urgency, and the quality expected of chefs in this ecosystem – ‘you simply can’t fuck up’,” he says. The fine-dining experience at Naar takes place between two rooms – the dining and the kitchen. “You start in one room, continue the tasting in the kitchen for a couple of hours, and then you come back.”

What sells isn’t exactly just the food, but the story and an intangible X-factor. He brings up the “boldness” of pop-ups and experiments run in other cities, like Benne – a dosa joint styled after Bangalore’s Darshinis, except a dosa at Benne sets you back Rs. 175. “It’s just a dosa, but people are lining up. What the fuck is going on!” The destination chef argues that food doesn’t need to be expensive for it to be an experience. “Going to a Shetty Lunch Home is also an experience, right?”

Yet this philosophy starkly contrasts with his own meticulously curated social media aesthetic. He’s got an unmistakable vibe that suggests he wouldn’t mind nabbing a star if he could. “Social media is salesmanship,” he declares. “I guess people also want to see who is cooking their food.”

The 'Juggling Many Kitchens' Chef

Known For: Papa’s Bombay, The Bombay Canteen, O Pedro, and Veronica’s

Bling: GQ’s Young Indian Influencer List in 2024; also a brief stint as the personal chef for Roger Federer

Hot take: “As a chef, you need to plate it like an artist and cook like a grandma.”

The Bear Inspo: Most definitely

Chef Hussain is everywhere, doing everything for each of the four restaurants he currently helms. Recently, he collaborated with several leading chefs, including Andy Allen of MasterChef Australia fame at O Pedro; Chef Mano Thevar at Papa’s; and Himanshu Saini at The Bombay Canteen. He hosted a Bear-inspired sandwich pop-up at Veronica’s and made an appearance on MasterChef India. Hussain made his way up the ladder sooner than he’d expected. Which is why, he says, he quit his job as a chef at a 5-star hotel in Mumbai to become a line cook and restart from the bottom – if you count being in the kitchen of the Late James Kent at Eleven Madison Park as the bottom.

Although he does admit that social media in general “changed the personality of the chef forever.”

As the eldest of a third generation of industrialists, Hussain was always expected to take over the family business. Instead, he went down the road less traveled and found his way into culinary stardom. Now, he’s the Executive Chef at four very big and wildly different restaurants in Mumbai, taking over from heavyweights like the Late Floyd Cardoz. His PR game is strong: there’s a Goan-style family photograph featuring him on the O Pedro homepage, glamorous awards being won, and promos for every new menu and pop-up he engineers. But he’s quick to clarify that he doesn’t use his social media in any way to market his work and that it is “just pure craft on display.” Although he does admit that social media in general “changed the personality of the chef forever.”

Papa’s is the newest fine-dining restaurant under his belt; a 12-seater right above his sandwich shop Veronica’s. This is how he describes the idea for it: “If I lived above my sandwich shop and threw a dinner party every night at home, what would that look like?” At Papa's, he does what he wants – like cook rabbit because he grew up eating Rabbit65 at Chettinad military hotels. He argues that he makes such ingredients “accessible,” because “at Papa’s, rabbit is served as a shawarma.” He also does ahi tuna in the form of a samosa and “everyone from any class of the society has seen a samosa in their life.” He calls these “luxe-stop dishes.”

He has a different approach for every place he works at. As the Executive Chef at Bombay Canteen he gets to “coax the most flavor out of ingredients”; at O Pedro, he's all about “[coming] from an informed space with the food,” which meant eight months of deep research – cooking in Goan homes to traveling to Portugal to craft the menu; and Veronica’s, of course, channels “the city of New York and [its] amazing food” into an artisanal sandwich shop in Central Bandra. All of these spaces, he says, “add to the different chapters in my life.”

The updated version of this article includes a brief introduction.

Vasudhaa Narayanan is the Creative Director at The Swaddle. She explores the complexity of identity, domesticity, and gender through the visual arts medium.