Tiny Mites That Have Sex On Our Face Are Facing Extinction

This is bad news for our skin.

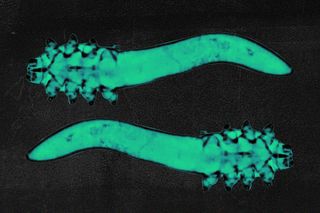

Your face is a home — to thousands of mites that quietly reside in your pores, eating away the dead skin cells. They come out under the cover of night to procreate on our noses, foreheads, and nipples. They then crawl back into the shelter of our pores, living static but secret lives. The human body is where the Demodex folliculorum live, breathe, and die.

“Don’t be worried. Be happy you have a small microscopic creature living with you, they don’t do any damage,” said Dr. Alejandra Perotti, an invertebrate biologist from the University of Reading, saying we should be “grateful” for the relationship we share with them. As many as 90% of people roughly carry them. “They’re very tiny and cute. There’s nothing to be concerned about having them,” she told Radio 1 Newsbeat. Just how tiny are they? About a third of a millimeter in length, tiny legs, and mouth attached to a sausage-like body. But D. folliculorum, the microscopic mites strongly dependent on humans for survival, may face an extinction threat as they evolve.

Perotti, along with other researchers, penned the findings of a new study, published in the Molecular Biology and Evolution journal this week. The mites have the smallest number of genes out of any insect or arachnid, and they share a rather symbiotic relationship with the human hosts. And this is particularly what’s killing them: the more they adapt to living under our skin, the more likely it is they will lose their genetic diversity, they will become entirely dependent on us for survival, and won’t bother to find a new mate to procreate with. In other words, they may become extinct as they gradually merge with our bodies. The tiny parasites are thus currently undergoing a gene loss that threatens the course of their evolutionary cycles.

The concern around their possible extinction came up when researchers examined their genetic make-up. They realized that the gene responsible for the sleep patterns of mites was absent. How were the organisms waking up then? They had adapted to detect lower amounts of hormones passed off in the skin while the human hosts sleep, and this served as a trigger to wake them up.

Related on The Swaddle:

Everything You Need to Know About the Mites That Live and Procreate on Your Face

“We found these mites have a different arrangement of body part genes to other similar species due to them adapting to a sheltered life inside pores,” explained Perotti. “These changes to their DNA have resulted in some unusual body features and behaviors.” Their genomes comprise the very bare essentials; this is partly because they have no competition and no exposure to other mites. Their DNA peculiarities are also why they don’t come around in daylight — they no longer possess the DNA that would have provided protection against ultraviolet radiation.

“They are also unable to produce the hormone melatonin, found in most living organisms, with varying functions; in humans, melatonin is important for regulating the sleep cycle, but in small invertebrates, it induces mobility and reproduction,” ScienceAlert further explained.

The conclusion of the study was grim: their existence which isnow anchored around people, and thiscould be causing ever-lasting evolutionary changes that are unprecedented in any mite species.

Their cuteness aside, why exactly should we care about their eventual decline? “They are associated with healthy skin, so if we lose them you could face problems with your skin,” Dr. Perotti added.

The contrary has been theorized for some time now. Scientists argued that the waste D. folliculorum secrete explodes when the mite dies (because they don’t have an anus), thus causing skin conditions. But the research also debunked this false idea: the tiny parasites do have buttholes.

And if anything, their presence keeps the skin healthy. “The long association with humans might suggest that they also could have simple but important beneficial roles, for example, in keeping the pores in our face unplugged,” said zoologist Henk Braig of the University of Bangor and the National University of San Juan in Argentina.

Alas, the secret lives of the D. folliculorum mites may forever be lost within our own bodies, as they crawl towards an evolutionary oblivion.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

People Were Stumped by a ‘Mysterious Spiral’ That Appeared in the Night Sky