To Prevent Bananas’ Extinction, Scientists Are Searching for Its Ancestors

The lack of genetic diversity in commercial bananas means that the arrival of a banana-specific pathogen could destroy the whole supply.

Bananas, known as a “food of convenience” in the developed world, continue to be a basic source of nutrition for many living in developing regions. However, the history, and possibly the future, of this ubiquitous fruit remains complex: the key to saving the latter could depend on the former. Now, researchers are in a bid to find the banana’s ancestors to do just that.

A new study published in the journal Frontiers in Plant Science attempts to build the banana’s ‘family tree’ by comparing genomes of wild and domesticated species. In doing so, they found that today’s domesticated bananas “are hybrids of different subspecies”. They also found evidence that common banana varieties have three “wild mystery ancestors” that are yet to be identified.

While there exist a large variety of wild and indigenous banana species globally, the versions of the fruit most commonly found and traded are domesticated varieties, mostly derived from the species Musa acuminata — all genetic clones of each other.

The lack of genetic diversity in the commercial variety becomes a crucial factor in understanding the crop’s increased vulnerability, especially in a warming world.The arrival of a banana-specific pathogen could destroy the whole supply.Finding the banana’s missing ancestors and introducing greater diversity in commercial banana consumption, then, becomes urgent in preventing existing species of this fruit from being wiped out.

As Rob Dunn puts it in a Wired report, “[I]n the native range of bananas lived a great diversity… In those same regions one could also find an extraordinary diversity of pathogens. But in the cultivated world of bananas… because a single genetically identical variety of banana was planted everywhere, were any banana-attacking pathogen to arrive, it would mean trouble. Any pathogen that could attack a single banana plant, even one, would be able to kill all of them.” Monoculture (single-crop) plantations thus have several negative implications, and cultivating genetically diverse, native species becomes crucial.

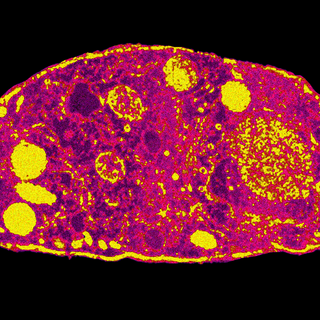

In their recent study, scientists used genetic sequencing techniques on 226 different banana leaf extracts to identify their unique genetic fingerprints. “At least three extra wild mystery ancestors must have contributed to this mixed genome thousands of years ago, but haven’t been identified yet,” stated Dr. Julie Sardos, a genetic resources scientist and one of the study’s authors.

This reveals a possibility of the existence of banana species or subspecies that have not yet been recorded by science. “Our personal conviction is that they are still living somewhere in the wild, either poorly described by science or not described at all, in which case they are probably threatened,” Sardos said.

The team of researchers also tried to identify where in the world these mystery ancestors might be found today. According to the study, the possible locations of these wild banana species could be between the Gulf of Thailand and the west of the South China Sea, between north Borneo and the Philippines and finally, the island of New Guinea.

Related on The Swaddle:

Are Genetically Modified Foods Safe?

Identifying these banana ancestors could help develop new ways to protect existing species from pests and diseases. Dunn argued for understanding the biology of the banana, if we are to prevent another catastrophic extinction of banana species, as was seen in the case of the Gros Michel.

In the 1950s, the Gros Michel variety, which had dominated markets, was wiped out due to the Panama disease, a fungal infection that affects banana plantations. The Cavendish variety, previously considered immune to the disease, rose in its stead and solidified its place as the new commercial species. However, recent reports have shown how the Cavendish variety too, is susceptible to the Panama disease.

The Panama disease has affected banana plantations across the world, including in India. With increased warming, plant diseases are expected to rise, further threatening global food security. A 2019 study published in the journal Nature Climate Change pointed out that banana yields could drop drastically in several countries due to global warming. India, one of the world’s largest producers of bananas, could be severely affected.

In 2017, Gert Kema, Professor of Tropical Phytopathology at Wageningen University & Research, had highlighted how Cavendish bananas suffer from a major drawback—the lack of genetic variation. “This means that the bananas of the big brands and fair-trade bananas are genetically identical. They are clones grown in extreme monocultures and are therefore all equally sensitive to fungal diseases,” Kema stated. He further added that ensuring genetic variation could be the key to tackling several problems in bananas, while also providing more choices for consumers.

Meanwhile, local varieties that show greater genetic diversity suffer from a lack of demand. According to Dr. M.M. Mustaffa, Director of the National Research Centre for Banana in India, the Indian market is dominated by the commercial Grande Naine (G9), a cultivar of M. acuminata. However, G9’s popularity has led to a decline of native species. Several efforts are being made to revive indigenous varieties. For example, Vinod Sahadevan Nair, a farmer from Thiruvananthapuram, has been recognized for growing over 400 varieties of bananas on his farm.

Understanding the genetic diversity across banana species could then allow cultivators to design “targeted and informed breeding strategies,” as the researchers pointed out in their recent study. “Without diverse genetic approaches to handling diseases, it wouldn’t take much for a single plague to decimate the global supply,” Science Alert noted. While global trade continues to remain dominated by a single variety, growing food insecurity also makes a case for increasing the diversity of our food systems and resilience of our farms by including indigenous species in the mix.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

A Podcast With AI‑Generated Steve Jobs Raises Ethical Concerns