Tollywood’s Kingmakers

How organized fandoms — the Telugu film industry’s best kept open secret — powered the RRR juggernaut.

The Men Who Built Gods

A blood bank in Jubilee Hills, one of Hyderabad’s most upscale locales, houses the office of a man responsible for spreading the word of an unlikely god.

A steep driveway leads into a tinted-glass building surrounded by crisp, manicured foliage. It’s uncannily quiet inside – a far cry from the city’s irrepressible churn on the other side of the compound’s high walls.

Uniformed guards stop us at the gate. We are there to meet the man who runs the operation – but the men refuse to allow us in without an appointment. Finally, one of them says, “You can go in, but no photographs – and don’t mention Sir’s name.”

A large display board just beyond the gates carries larger-than-life images of the Tollywood actors Chiranjeevi and his son, Ram Charan Tej – the latter in mid-power walk, one hand in his pocket, with aviators; the former frozen in the act of wearing sunglasses. Between them are the words, “EYE NEVER DIES, DONATE EYES,” and just below, a single, gigantic, hyper-realistic eye with a blue pupil that’s built to blink with the brush of wind. And below that, in bold red letters: “Akhila Bharatha Chiranjeevi Yuvatha.”

This is the Chiranjeevi Eye and Blood Bank, where a few attendees outside are leaving with certificates of appreciation for donating their blood – digitally signed by Ram Charan and Chiranjeevi. Their faces flank the lettering on the certificates.

At the reception, women at the desk speak the name the guards asked us not to utter in hushed tones, arranging an appointment. To their right, glass doors lead into the donation center, wafting antiseptic fumes, where a few men lie staring at the ceiling while their blood is drawn. Above the door, an LED screen shows muted visuals of Chiranjeevi, addressing the waiting room in a pre-recorded video. Hands folded, he smiles beatifically, expounding on the virtues of donating blood. The video cuts to show a crush of people arriving at the center to volunteer.

Above the receptionist’s desk, a large portrait of Chiranjeevi in politician-white linen smiles down upon us. On the opposite side, another portrait – this time of his character in his latest film. And behind us, a glass cubicle houses the man we’re here to meet. He’s wearing an over-starched linen shirt. His fingers gleam with multiple gold rings. Several attendants flit to his side, relaying his appointments. On the two walls of his office that aren’t glass are large portraits of Chiranjeevi; on the wall behind him, the Chiranjeevi portrait is flanked by those of Mother Teresa and Abdul Kalam. A tiny figurine of the Hindu god Hanuman is on a side-table – almost an afterthought.

The receptionist sends us to a second receptionist, who sends us back to the first, before they ask us to wait further, both heads bowed while they tentatively make the request on our behalf. But we’re finally allowed inside. He introduces himself: Ravanam Swami Naidu, the founder and President of the Akhila Bharatha Chiranjeevi Yuvatha, and the man who runs the eye and blood donation center set up in Chiranjeevi’s name. Mr. Naidu is the fandom equivalent of a Pope, a man blessed with proximity to Chiranjeevi and burdened with the responsibility that comes with divine access.

He starts by telling us how he got here. As he came of age in the 1980s, he had watched Chiranjeevi from afar for years, yearning for a chance to speak with him. “I spent my scholarship money to travel to see him, wherever he was,” he told us. “I slept in empty movie theaters the night before his movie release; on the morning of, I offered prayers and worshiped the film reel.”

Chiranjeevi’s fans, as Naidu recalls, would arrive in busloads to see him, without prior organizing. “When we realized how many of us there were, we began forming groups,” Naidu said. Eventually, they worked out an arrangement with Chiranjeevi himself – they’d organize themselves and meet him systematically, on weekends, when different fan associations would take turns to see him. But somebody had to lead the effort. This coalesced into the Rashtra Chiranjeevi Yuvatha, the umbrella fan association that encompasses thousands of others – and these are just the registered ones.

Half an hour into reminiscing about the genesis of the fandom, we ask him what Chiranjeevi means to him, and Naidu’s tone shifts. “We are his bhakts,” he says reverentially. Devotees.

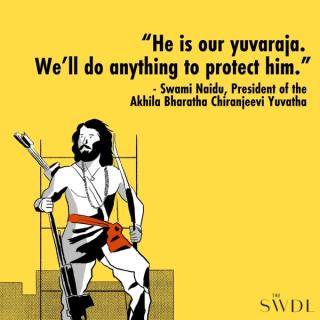

We ask Swami Naidu whether he sees Chiranjeevi’s son, Ram Charan, the same way, and whether he inherited his father’s divine power. “Of course. His is our yuvaraja [young prince]. We’ll do anything to protect him.”

And so it was that when Ram Charan starred in RRR – a 2022 film that prompted a tectonic shift for not just the Telugu film industry but Indian cinema as a whole, the film was carried to success on the shoulders of legions for whom his father, Chiranjeevi, is God.

But he wasn’t the only yuvaraja in RRR: there was someone else who directly also descended from a god-hero.

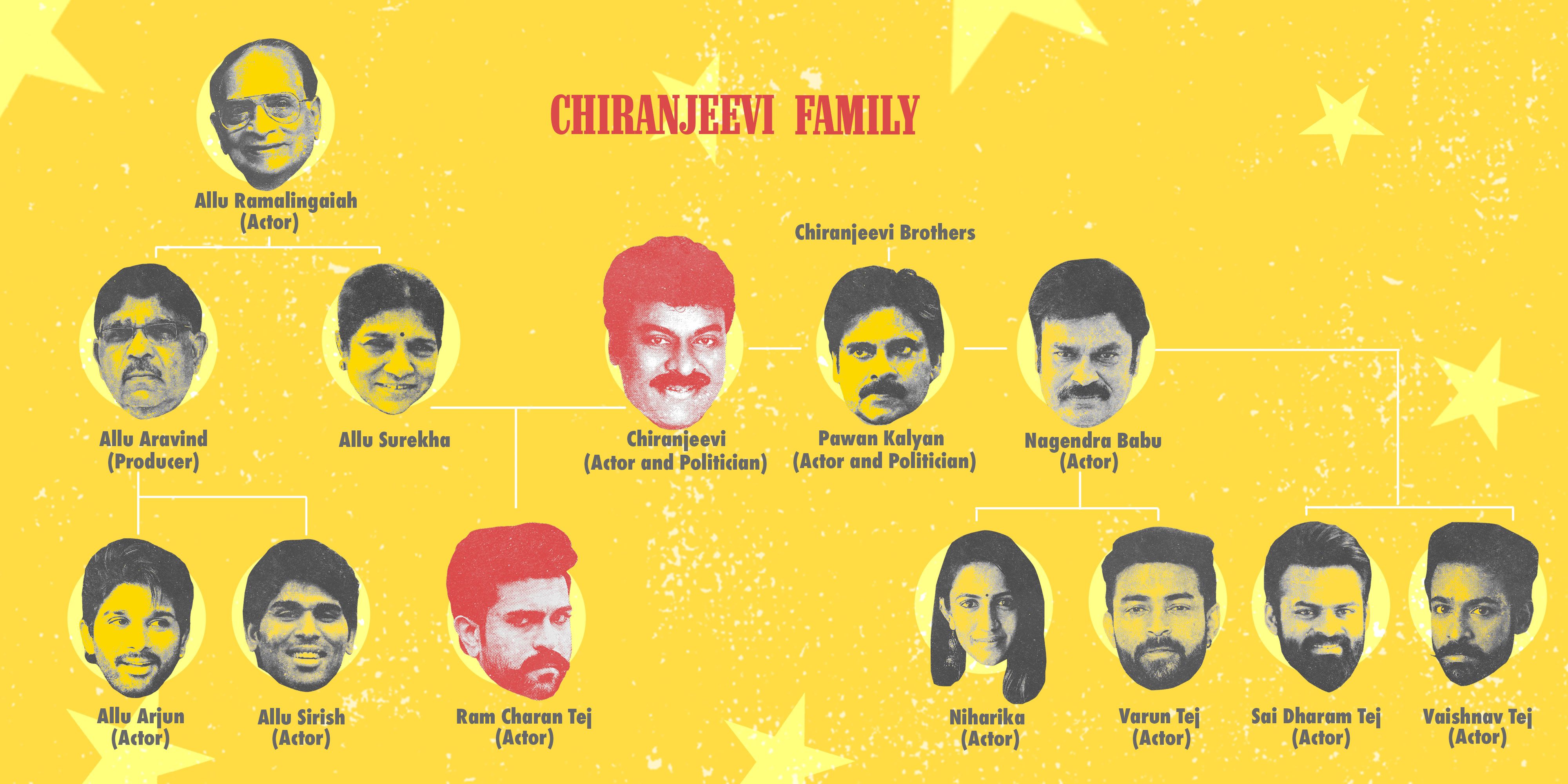

Jr. NTR, the co-star of RRR, inherited some of his popularity too. His family spans many generations of actors, each of whom have their own fandoms. His grandfather, Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao (NTR), was an actor one generation before Chiranjeevi but comparable in star power; when NTR essayed gods, his face became god’s own for many in the Telugu states – and that was before he became the Chief Minister. Jr. NTR remains arguably the only family member in a large clan to bear a striking resemblance to the patriarch.

“He has [had] an aura from birth,” says Sai Mohan, an ardent fan, about Jr. NTR. “He’s the only one who really carries on the legacy.” Where Cheeranjeevi’s family combined stardom with social work, the NTR clan leveraged fame into political power, resulting in Jr. NTR becoming the scion of one of Tollywood’s – and Andhra Pradesh’s – oldest and most powerful families.

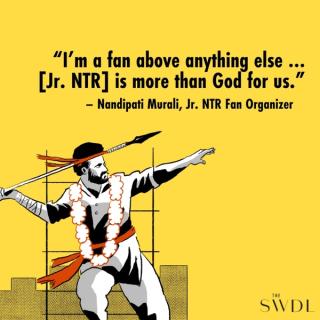

“I’m a fan above anything else … he [Jr. NTR] is more than God for us,” said one man whose identity is elusive but who has the ear of his idol more than anyone else in the Jr. NTR fandom. “It’s not just devotion, it’s pichchi [madness].”

The story of RRR reported by most has focused on the combined box office pull and international appeal of these anointed descendants. But Ram Charan and Jr. NTR joining forces marks much more than a never-before-seen collaboration. It is the culmination of nearly a century of several people in search of divinity that they could call their own. The communities that backed each star were more alike than they were different – but more divided as a result of their similarities. But when the children of the gods they had made in their own image finally came together, the world was bound to hold its breath.

A Tale of Two Dynasties

Not everyone has access to gods equally. In Andhra Pradesh and

Telangana, the two Telugu states, people have created their own gods – constructing the divine from the bottom up.

The time was ripe. Post-Independence India was a nation in search of its soul. No other sovereign territory had as many languages or cultures, and few were as socially divided.

The caste system, or varna system, had been in place for centuries, as laid out by Hindu scriptures like the Manusmriti. The hierarchy imposed one caste upon the other, in four tiers, or varnas – Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra, collectively called Savarnas. Avarna described another, supposed “sub” tier – the current-day Dalit communities who were subjected to social exclusion and ‘untouchability.’ In this system of graded inequality, as Dr B.R. Ambedkar calls it, “the Shudra is not only placed at the bottom of the gradation but he is subjected to innumerable ignominies and disabilities so as to prevent him from rising above the condition fixed for him by law.” In Hindu society, Shudras were the lowest of the low, with the exception of the Avarnas. In a culture inseparable from this system, the first three ‘tiers’ were (and remain) the gatekeepers of political power, worship, and culture.

In erstwhile unified Andhra Pradesh, however, a handful of Shudra communities had amassed wealth and influence. Since being endowed centuries ago with generous land grants and titles by Nizam rulers for being expert cultivators, a few once-agricultural peasant communities had prospered – doubly so in the two decades post-independence, during the Green Revolution. The Reddys and Kammas and, to a lesser extent, the Kapus owned most of the land in the state. And in due course, the Reddys began wresting control of the state’s politics and media from the Brahmins and Vaishyas. Telugu films, in turn, began to cater to the Reddys and their fellow equivalent castes like the Kammas. But community memory is long: thousands of years of Savarna indoctrination and slights kept these castes feeling on the backfoot.

And in some ways they were; these communities were still bereft of spiritual autonomy. It didn’t matter how much power or wealth they accumulated or how much they had risen in the caste hierarchy, the majority of people in the state did not have access to divine figures who supposedly represented them. For centuries, Brahmins had been amassing control of temples and worship and discouraging Shudras and Dalits from claiming and communing with deities, or otherwise drawing spiritual nourishment without a Brahmin intermediary.

The great epics have always shown one thing to be true: gods are born when people need one to call their own. And it’s usually someone ordinary – but with an innate destiny to be chosen.

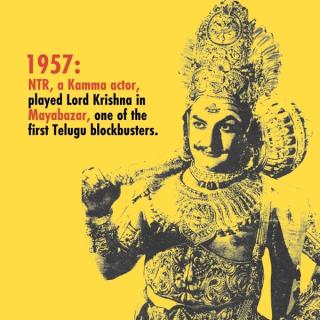

Enter Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao.

.jpg?w=320&h=160&auto=format)

Now known simply by his initials, NTR began as a small-time Kamma actor, a “walk-in” character in an industry of Reddys and Brahmins. But within less than seven years, he portrayed the Hindu deity Krishna in one of Telugu cinema’s first and biggest blockbusters, Mayabazaar (1957). He went on to play other popular mythical figures and, in time, emerged to fill the increasingly noticeable gap between the Kamma community’s prosperity and their power compared to their cohorts and rivals, the Reddys.

His performances as various gods permanently etched his face into people’s minds as a stand-in for gods they were used to worshiping from a distance. He was, quite literally, a god in their own image. His meteoric rise to popularity led to the first large-scale following that fought for him, in his name, and identified with him – a fanatic collective of devotees that eventually propelled him to the position of the state’s first Kamma Chief Minister.

“Until [NTR became Chief Minister in] the 1980s, Kammas and Kapus didn’t have political gods… NTR was an alternative [to Reddy] hegemony for the Kammas and Kapus [to achieve] political godhood,” explains anti-caste intellectual and political theorist, Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd. NTR leveraged his cultural power into political power when he launched the Telugu Desam Party (TDP). “Once NTR became a politician, his god image became household in the form of huge photographs in houses, cutouts, statues.” The Reddys had lands and politics; Kammas had land, cinema, and now politics. Meanwhile the Kapus, who had initially rallied behind NTR, were left with nothing more than they started with.

Until Chiranjeevi entered the scene.

.jpg?w=320&h=160&auto=format)

As NTR was ascending to absolute power, a young upstart began shaking up Tollywood. Chiranjeevi entered a film industry already replete with titans – all from the Kamma community. These were men whose fans organized and fought with one another – sometimes to the death – about who was the better human, hero, idol. In a cultural milieu oversaturated with men elevated to divine status, there was seemingly no room for anyone else – except, once again, an outsider who could change it all. Like most major historical shifts, the need for a new, larger-than-life idol repeated itself. There are never enough men to represent all men; a new pantheon of gods was inevitable.

Chiranjeevi was the first person from the Kapu community to cement a foothold in the industry. Unlike the previous generation of actors, Chiranjeevi’s characters were all working class, caste-ambiguous (but lower-caste coded), rough around the edges, and resonated with the realities and aspirations of the masses. In his breakout hit Khaidi (1983), he portrayed the angry young man who sought retribution against an oppressive, bloodthirsty feudal lord. The first Telugu “mass” movie star was born. Kapu youth began to fill up theaters. Then they came back for more, watching his films 10, sometimes 20 times. But something was different here: Chiranjeevi’s image challenged what it meant to be divine. Dalits and backward castes were drawn to a hero who represented them just overtly enough to elevate them cinematically; Kapus were drawn to a hero who represented them just overtly enough to elevate them in real life. His divinity coalesced around a success story – where an ordinary man started from the bottom and ascended through grit. Only later would fans look back at him as divinely ordained.

“He played the role of Cobbler in the famous Swayam Krushi, he was a rickshaw driver, union president of a vegetable market; he represented us like no other heroes of that time did, in an assertive, speak-truth-to-power kind of roles. When I watched his films, I wanted to play the roles he did, in real life,” says filmmaker and political scientist Bala Gurundam. “Whenever a Chiranjeevi film released in our wadas, the Dalit-Bahujans used to say, ‘Our man’s movie has released.’ He became one of us unlike any other actors of that time.”

Chiranjeevi quickly developed a following that only Kamma stars had previously enjoyed: if NTR was given the moniker “messiah of the masses,” Chiranjeevi was the masses. After a certain level of stardom, the difference between the two wore thin: one had become god and the other was on his way. Having tired of rallying around Reddys and Kammas in the name of anti-Brahminism, Kapus needed their own god. But their numerical strength alone wasn’t enough. With additional support from Dalits and backward castes, however, Chiranjeevi’s following acquired a magnitude that any politician would envy.

Aside from shared love for the same star, fandom didn’t translate to an alliance between Kapus and Dalits. Kapus had been left behind economically, turning them into a backward community relative to the Kammas and Reddys – and culturally, relative to Brahmins. The sociologist Christophe Jaffrelot described their plight as one characterized by insecurity – of being surpassed by their social equals, the Kammas and Reddys, and of being equaled “from below” by more marginalized Dalits and Adivasis.

As a result, they developed “a sub-culture… primarily based on macho pride,” says Gita Ramaswamy, a former CPI-ML member and activist in Andhra Pradesh. Simultaneously, there was “a sub-culture of the Kammas dependent entirely on property and wealth… Much of this is fostered by cinema.” It’s why many of Chiranjeevi’s films centered relatable, son-of-the-soil characters, while his contemporary (and son of NTR) Balakrishna’s tend to center feudal lords, benevolent village patriarchs, or faction leaders.

“Whenever a Chiranjeevi film released in our wadas, the Dalit-Bahujans used to say, ‘Our man’s movie has released.’ He became one of us unlike any other actors of that time.”

As these subcultures spread, they ushered in the deepest irony. On the one hand, they were the result of communities that felt sidelined and hungered for a powerful figurehead to speak for them. On the other hand, the subcultures were rooted in caste pride, which translated to pride at someone else’s expense. And that someone was almost always Dalit communities. The period of NTR’s chief ministership saw brutal killings of Dalits in Karamchedu, Andhra Pradesh, with the Kamma perpetrators escaping punishment for more than two decades. Ramaswamy has extensively documented the ways that Reddys, Kammas, and to an extent Kapus, have colluded to keep their dominion over land and feudal power – at the expense of communities far bigger, but more marginalized, than themselves. In their bid for power, these Shudra subcultures fought their way up, while crushing (often brutally) whoever was below.

By the early 90s, these subcultures had coalesced into fan organizations doubling as caste organizations, with larger-than-life cut-outs of NTR and Chiranjeevi, banners, and worshiping ceremonies for each spreading across the region based on caste demographics. Although the caste motifs are less obvious today, subtle signs remain, especially online. For instance, the website for the Kapu Naidu Sangam, a caste-based organization for Kapus, has numerous downloadable wallpapers, posters, and articles pertaining to the Chiranjeevi family, but none at all of NTR or other Kamma families. Similarly, a Chowdary – a caste-marking suffix taken up by Kammas – tea-stall might carry the faces of NTR family on its storefront. On social media, actors as signifiers of caste have taken a new form: Facebook groups or fan pages for either of the dynasties, are vehicles to showcase caste-pride. “[Kammas and Kapus] compete with each other in getting agricultural labour, in control over village politics and control over culture. How could they cooperate in this context? It is in the competition over culture that films are important,” says Ramaswamy.

Over time, the caste-fan subcultures acquired a characteristic, visual form. “NTR was the first to promote his roles with posters, cutouts, and so on – maybe he had a political future in mind, which he successfully carried forward into his Chief Ministership. After NTR, Chiranjeevi emerged as a fan organizer. The divine construction of heroes is based on this [ubiquitous imagery],” says Shepherd.

The Politics of Caste

From the smallest hamlet to the largest cities, public spaces were redrawn

as sites of worship for competing gods. In the late 80s to the early 90s, the conflict between fan associations of Chiranjeevi and actor Balakrishna (NTR’s son, then seen as his successor) in Vijayawada became so fraught that the city was spatially divided into designated fan territories, according to S.V. Srinivas, a film studies academic, who studies Telugu cinema and fan cultures.

What began as devotion turned into a quest for control. “There is an insistence on reading the [hero’s] image as if it were real,” says Srinivas. If any character their heroes played had negative characteristics, the film would be met with outrage and threats to boycott or even commit suicide.

The heroes’ image had to remain sacrosanct both onscreen and off – anything that disrupted that became sacrilegious. Further, Congress Party supporters often found themselves in Chiranjeevi’s fan associations, and vice versa, while supporters of TDP (founded by NTR) aligned with the NTR and his son Balakrishna’s fan associations. The lines between fandom and politics thinned, leading to a “trisection,” as Srinivas puts it, between cinema, politics, and caste.

Though the Chiranjeevi family briefly flirted with politics in the 2010s, when the time was ripe for them to transition their careers to political power, the endeavor unexpectedly failed. The post-liberalization 21st century was one characterized by options in the marketplace. This was true of idols too, and people seemed to need political gods less than they did earlier. Fans who formed an identity around Chiranjeevi’s icon shored up their power in other ways – through organized social work, like the eye and blood bank.

Today, Reddy-Kamma-Kapu dominance is still fenced within the Telugu states. At the national level, these castes continue to be locked out both politically and culturally, as many locally powerful Shudra communities in Southern states are. Dominant Shudra communities may acquire and hold on to power to an extent, but cannot reach a place in the national imagination.

In the spiritual domain, priesthood is still not accessible to Reddys, Kammas, or Kapus even now, points out Ilaiah. There is a very deep rooted alienation from day-to-day access with god. No matter how powerful or upwardly mobile, none of these Shudra castes can reach Hindu deities, directly commune with them, or see their own aspirations reflected back.

Ilaiah describes these communities as “neo-Kshatriyas,” a varna (tier) just below Brahmins in the varna system, for how they project themselves.

Their gods, two scrappy outcasts who climbed a cinematic and political system and stomped on top of it, would appeal to fighters. And if the vastly expanded demographic of fandoms is anything to go by, the two dynasties and the gods they produced no longer represent singular castes as strongly as they once did. The head of a Balakrishna (NTR’s son) fan association in Anantapur is Muslim; some leaders in the NTR family fandoms are Kapu; and Chiranjeevi fandoms comprise Kammas too. Even Brahmins and Reddys participate and remain loyal to a variety of fandoms across the two dynasties. It’s an appeal that may have begun with caste but ended as a neo-religion, one that’s too large to be contained to any single community.

But caste is an insecure, jealous beast that wasn’t made for absolute inclusion.

Decades after NTR’s and Chiranjeevi’s debuts, the 2022 film RRR brought their heirs together. It marked a paradigm shift. As a national phenomenon that quickly turned international, it meant more than a universal Telugu pride. With their god-heroes – Jr. NTR and Ram Charan – carrying them, it was a win for both fandoms.

Moreover, it seemed to have ushered in change for Indian fan culture as a whole. “Certain aspects of fan activity seem to be spreading across India,” Srinivas says. “Dancing in theaters is now becoming a national phenomenon. Public enjoyment of the film is now spreading.” Screenings of RRR across the world had frenzied dancing inside theaters, and managements abroad complained of paper cuttings and confetti inside halls. This used to be part of single-screen culture; multiplexes, meant for a “class” audience, never allowed it. It’s a cultural syncretism that’s been brought about by the people for whom movies have meant everything – including their own identity.

But through their respective stars, only the Kammas and Kapus had finally made it out of the Telugu states.

The Devotees

Every god needs believers. But where do they come from – and how can they keep them?

“What is a religion? It is an organization which does everyday activity in some form or the other. This is also true of a political party. So it is with cinema industry fan groups. They have to do some activity everyday. It doesn’t differ from religion or politics – it’s more or less the same,” K. L. Prasad, a screenwriter and director, tells us in the dilapidated Screenwriters’ Association office. “Today, heroes are imprisoned by their own image.”

That image is a mosaic of fan anxieties, emotions, and fixations, around which a singular identity coalesces. That’s what makes it difficult for a fan to love, admire, or worship anyone else. Doing so would fundamentally upset who you are. “Can you lose your identity?” Prasad asks rhetorically.

It’s a question that’s critical for a fanbase to expand – and thereby expand their hero’s influence too. At a certain point in order to attain the desired power, a religion’s ranks must be swelled by outsiders. This is the current state of Telugu film fandom. Nagendra Kumar, a fan of Jr. NTR, for instance, was involved in a fan-fight during the release of RRR. Notably, none of the people involved in the fight were either Kamma or Kapu. Many declined to elaborate when we ask them how caste plays out in fandom.

“Caste feeling has reduced, hero feelings have increased,” as Kumar puts it. “Caste communities are not large enough to produce a success of this size… Jr. NTR is by no means the poster child of the Kamma hero,” says Srinivas. There’s no denying that there is a sense of identity formed around movie stars, of which caste is just one part. But caste isn’t completely out of the picture – yet.

“When I screened RRR, of the 550 seater capacity, 500 tickets were given to the stars’ caste community people,” says Shakti Pandraveti, who owns a theater in Tirupati, about opening day collections. “Another theater owner, who is a Chiranjeevi fan, said he would only screen the movie for other Chiranjeevi fans. NTR fans then came to us – I’m not from either community, but we can’t control them.” During day one any film’s release, only caste-groups dominate the theaters in Andhra Pradesh, in his experience.

RRR’s success in the United States also has to do with the sense of identity that emigrants from the Telugu states hold on to. The IT boom in Hyderabad led to many from the dominant castes moving abroad, Pandraveti says. Today, Kammas and to an extent, Kapus hold on to their caste-based identity in the US. Venkat, a distributor in the US, says that older fans of Chiranjeevi and Balakrishna are more driven by caste than the younger generations.

Back in India, RTC Crossroads in Hyderabad is where devotees collide – it’s also where the images of stars loom over worshippers. Here is where fans decorate cityscapes with images of their stars as they see them – larger than life, powerful, and domineering. Images of a magnitude that no mortal could possibly measure up to. But they’ve never seen their heroes as mortals.

Around the area, huge cutouts of Balakrishna (NTR’s son) and Chiranjeevi stand as sentinels to a city growing bigger and more restless around them. It’s a junction that hosts some of the Telugu film industry’s most iconic theater landmarks: Sandhya 70mm, and Sudarshan 70mm and 35mm. These are two separate single-screen theaters that every single producer and distributor must watch closely: If a film is successful at The Crossroads, it’s a hit. The RTC Crossroads fan associations decide.

Fans, their associations, and their leaders form a parallel civil society – organizing charity and relief and decorating cities and towns with banners and cutouts of their favored stars. Though the industry has five big dynasties, fans of NTR’s family and Chiranjeevi’s family in particular have the most fraught history – one that’s rooted in identity, power, and a much more nebulous quality that eludes understanding but is essential to the making of a star.

A gigantic effigy of Chiranjeevi, approximately 50-feet tall, towers over Sandhya 70mm, with an equally opulent garland around his neck. It was put there by a crowd that formed a human pyramid to reach the top. Heavy-duty machinery is deployed to transfer gargantuan garlands for the process; during opening day, cutouts like these are bathed in gallons of milk. All around, posters of his latest film Waltair Veerayya feature the names of the fans who printed them and the fan associations they come from. Even the film’s opening credits thank specific fans alongside producers, veteran actors, and sponsors. The compound is empty – but the devotees are everywhere.

The film is being screened as we arrive; it’s on its 50th day of theater release. In the lobby, a few men are seated near a wall carrying trophies, mementos, and souvenirs.

A closer look shows that the items in the shelves are all related to Chiranjeevi, his son Ram Charan (co-star of RRR), his nephew actor Allu Arjun, and his brother actor-politician Pawan Kalyan. “Presented by Konidela Yuvasena,” one tribute says, commemorating the 100th day of an old Ram Charan film. The whole display is a tribute by fans who have come to be known as “Mega Fans,” after Chiranjeevi’s screen prefix, Megastar. Mega fans encompass all four men’s fandoms. But increasingly, each star’s fanbase has evolved into its own force (‘Allu Army’ or ‘Pawanism,’ for instance).

The fans we spoke to didn’t wish to be named. But they represented the Konidela Yuvasena – Konidela youth army. Konidela is the Chiranjeevi family surname; this is a fan association that sways the Crossroads’ collections and also drives re-releases of old Chiranjeevi films. “The biggest cutout was 100 feet,” one of them says, when we asked about the cutout outside. “Fan culture as we know it today started with Chiranjeevi: garlanding, throwing confetti in theaters, pouring milk on effigies.” They tell us that, often, it’s distributors who provide the effigies: fans bring the posters, decorations, and everything else. Throughout the conversation, the men refused to take Balakrishna’s name – almost as if the NTR family name was heretical.

On a perpendicular street is Sudharshan, the other landmark where fans converge or clash. This is the site for the most feverish displays of devotion for actor-gods, of whom there are now many – though none with the socio-political capital of the NTR and Chiranjeevi families. Here is where fans of the actor Ghattamaneni Mahesh Babu – another heir of another Kamma dynasty in Tollywood – nearly set the theater ablaze by bursting crackers inside the hall during a recent re-release. Sudharshan’s corresponding fan wall is full of memorabilia commemorating Mahesh Babu and his father, actor Ghattamaneni Krishna. There are a few dedicated to actor Balakrishna (NTR’s son) – “presented by Citywide NBK Fans RTC Crossroads” – as per the inscription on the base. The Kamma dynasties were everywhere in these walls. Noticeably absent: anyone from the Chiranjeevi family.

We’re taken upstairs to meet Raj, the proprietor of Sudharshan, in his office. “After RRR… our manager can solve the Russia-Ukraine crisis now,” he quips about the manager by his side. The manager’s career spans nearly two decades, and he’s the conduit for fan groups to negotiate with one another. He has fan association numbers on speed-dial, and he mediates meetings between fan groups when two heroes’ films release at the same time, or close together.

At these meetings, they decide how much space to dedicate to which hero’s cutout, timings for each fandom to carry out their celebrations, and which older movies are re-released.

Videos of the opening day of RRR at Sudarshan show a stampede; huge cutouts of Jr. NTR and Ram Charan are placed side by side. Fans of Jr. NTR scream, chant, and pray before his image, which is illuminated in a fiery red glow from flood lights shining up to him. On the other side, Ram Charan fans do the same. It’s a secular event – two religions work to peacefully coexist and express their devotion, giving one another room to exercise their faith.

But secularism in India has always meant something different than it has in other parts of the world – the church and state have never been separate here. Where there are too many religions, there’s tension underneath a seemingly calm surface. In the world of fandoms, the deities are simply too big for coexistence to be a regular occurrence – making RRR the once in a lifetime occurrence that it was. “The actor’s figure that you see [on screen] is thirty times bigger – this imprints into the minds of fans,” K.L Prasad says.

Many take it upon themselves to sustain the enormity of that image. Of them, a select few work to magnify it further.

The Interlocutors

Interlocutors exist in every religion, and it’s their job to jostle for space to

showcase their deities to the masses. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, being the intermediary between stars and their fans is a job that many covet for its proximity to the stars but few can attain.

The guardian-gatekeepers are subservient to their gods, yet domineering to fans; they speak for both. They mobilize first around one identity, then pivot to portray a secular, welcoming religion so the words of their idol reach more people. That’s why when fans open libraries, donate blood, organize healthcare needs for the poor, or set up orphanages, they do it in their heroes’ names. “I don’t think the fan club is a service organization… They do carry out a lot of publicity and outreach, but it’s all in service of promoting their star,” Srinivas notes. Good deeds become soft power.

Naidu seems to have mastered these dichotomies. “I have had a three decade-long career working with him [Chiranjeevi]. Still, I can’t stand in his presence for longer than 10 minutes. He is the Sun, a thousand Watts light – we’re all zero.”

Naidu says that Chiranjeevi is the divine avatar who has come to Earth to save us from the kal yuga,the age of the apocalypse in Hindu mythology. “During Covid19, when two chief ministers threw their hands up, Chiranjeevi garu (an honorific) stepped up. Under his patronage, his fans provided oxygen to dying villages – that’s why, despite coming into contact with the virus, we’re still alive. It’s because he protects us.”

It’s an invocation reminiscent of political leaders and godmen during the pandemic, who promised similar rewards for believers.

Yatendra, who works closely with Swami Naidu, says he has donated his blood 34 times as a fan of Chiranjeevi’s. He also donates to an orphanage every year on Chiranjeevi’s birthday. “I am not that kind of fan,” he says, about the theater celebrations. It’s a thin line. “We focus more on social activities… Movies release once every three to six months, and we’re a part of the celebrations when that happens. But during the rest of the time, we look into other ways.”

He’s one of thousands of fans who look to blood donation camps as a tribute to their hero’s successes and milestones. He says the Chiranjeevi Eye and Blood Bank issues ID cards and certificates to fans who have donated, allowing them to meet Chiranjeevi in the flesh. In honor of the 50th day of the film Waltair Veerayya, Yatendra organized another camp – at Sandhya theater. “Because of this one man, there has been so much change,” he says, referring to the rising popularity of blood donation as a cause.

Yatendra also organized the release of Chiranjeevi’s brother, Pawan Kalyan’s film Jalsa with the help of a production company run by Chiranjeevi’s brother-in-law Allu Aravind. At the company’s suggestion, “we collected one crore rupees from the release and donated it to the families of farmers who died by suicide,” Yatendra says. The rest went to the Jana Sena Party, a political party founded by Pawan Kalyan. “This was not commercial, this was completely for a social cause,” Yatendra claims.

Yatendra was offended by the classification of Chiranjeevi as a mass hero and chose his preferred description carefully: “Who says he’s a mass hero? The magic of Chiranjeevi is that mass audience, like auto drivers; class audience, like IT professionals; even ladies like you are his fans. He’s beyond all. You can call him a universal hero.” Here is the interlocutor, creating spaces for his hero’s image as he speaks.

What about other heroes – do they have the same universal appeal across caste, class boundaries? “I can’t comment on other fandoms,” he says. The disciples are diplomatic – they only speak for their own work, and they hope it speaks for itself.

The Jr. NTR fandom is humble, says Nandipati Murali, the equivalent of Swami Naidu for Jr. NTR’s fandom. “Unlike other fandoms, we don’t boast about our social work. We do what we have to – it’s the doing that counts.” Murali also does work for TDP, the political party founded by NTR, and accompanies Jr. NTR to political-cum-fan rallies, but he’s vague on the details. It’s a feature of the Balakrishna (NTR’s son) fandom too, whose senior members shared sparse information about what they do as party workers.

Where they see humility, however, others might see a shadowy reticence to convey more. But Murali does seem to have an eye on the long game. “Our hero doesn’t have political intentions for at least another 10 years,” he says, “as far as I know.”

Murali’s self-described “madness” for his hero gives him the legitimacy to represent the fandom. “I am his biggest fan. People don’t call me Murali, they refer to me as NTR Murali,” he says. His diplomacy when it comes to representing inter-dynasty tensions arguably work in Jr. NTR’s favor. At only 30, Murali already wields the power to influence fan wars. Raj, the owner of Sudharshan theater, tells us how once, when Jr. NTR’s fans accidentally ruined Pawan Kalyan’s hoarding for his film Vakeel Saab, things got heated at the theater and insults flew across NTR and Chiranjeevi fandoms on social media. The owner says that tensions dissipated only when Murali tweeted: “It was an unintentional incident. Inconvenience caused is regretted. All the best to Vakeel Saab and fans.” The tweet allegedly put an end to speculation that the damage to the hoarding was an intentional attempt to insult the Chiranjeevi family, and thus de-escalated a situation that could have precipitated into violence. “If I hadn’t tweeted that, it would have become a fight,” Murali says.

“Our goal is to give a good name to NTR and set an example for other fans.”

Murali also organizes events that involve Jr. NTR himself, even making fan dreams come true by having their star visit their functions. But he insists he’s neither Jr. NTR’s personal assistant nor his friend – despite others describing him as such. His activities aren’t confined to the fandom’s homebase at RTC Crossroads. “I oversee everything in Hyderabad.”

Murali’s commitment to the family began before he was born. His grandfather used to run auto rickshaws. During Indira Gandhi’s regime, when his grandfather’s business suffered, NTR stepped in to help financially, Murali claims. The story became a treasured family heirloom. Murali’s father became a fan of NTR’s son Balakrishna – and Murali was destined to follow the next generational heir.

“Since childhood, it was just this – nothing else.” Other fans regard their hero as god. Does he? “I regard him as more than that.” Like Swami Naidu, Murali grew into his devotion as he came of age. He has a photograph of himself with Jr. NTR from when he was 15 years old, and he claims he’s among the youngest to have been a superfan.

Like other fan leaders, Murali organizes social work on specific occasions related to the star: the hero’s birthday, during his film releases, re-releases, anniversaries, and milestones. “We celebrate his birthday like it’s a wedding, a festival.”

But it’s his ability to shape the narrative around his god that has turned him into a direct intermediary between Jr. NTR and everyone else. He claims credit for the idea of strategizing a peaceful RRR release by calling all stakeholders for a meeting prior, to figure out ways to prevent fights. But it was on the guidance of Jr. NTR, he says. “We’re committed; our hero has guided us and asked us not to fight.”

It’s the words of a man trying to brand the fandom as much as the god he serves. It’s a far cry from the overt caste-pride of NTR’s time: the vocabulary speaks to a much more inclusive community. It broadens the appeal. “We don’t have caste here; devotion doesn’t have caste. Caste is a politics thing,” he says.

Most fans agree with the sentiment: caste in fandoms is an older relic. But a few – who didn’t wish to be named – maintained that it’s still a driving force, especially for leaders to organize.

Nagendra Kumar, who works with Murali, has arranged for some portion of his money to go to a charity in Jr. NTR’s name. “Even after I die, my devotion for Jr. NTR will remain,” he says. Kumar is a member of the RAW NTR Trust, a welfare organization, whose goal is to onboard 10,000 fans as volunteers for social work. “If there’s a problem in any town or village, a member of the RAW NTR Trust steps in to help – even on behalf of the government.” They’re fans of NTR’s whole family – but mainly Jr. NTR. Kumar is the vice president of a district wing of the Trust in Andhra Pradesh. “Our goal is to give a good name to NTR and set an example for other fans.”

It’s hard to say whether the charity drives, library openings, blood donations, and healthcare support also contain the more aggressive tendencies of how fandom can manifest. All religions that currently exist do so in shades of black and white: benevolent and just, but willing to turn violent if they must. But what they all share in common is that, often, good work is a means to an end. Here, social work is in service of constructing an image. The more powerful the image, the better for everyone involved – almost.

In the ecosystem of devotion, there’s something to be gained at almost every level. Security, peace, and meaning are some – but often, it’s power. In Telugu cinema, as in any other, power is money.

The Business

The success of any film is measured by the size of its box office returns.

In Tollywood, films are carried on the shoulders of gods. But the gods are only as good as the money they rake in.

In most cinema industries, the chain of money goes like this: producers finance a film; they sell the film’s rights to distributors; distributors then license the film over to exhibitors (theater owners, in most cases), who then share the proceeds from ticket sales.

In the Telugu film industry, however, fans with influence are present at nearly all levels in the chain. Murali is a distributor and financier; Yatendra, who is the Rashtra Chiranjeevi YuvathaSecretary, is an exhibitor, someone who screens a film in theaters.

“I’m the one who started the re-release trend,” Murali said. He’s referring to an ongoing phenomenon in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, where old films are being screened once again in theatres for the benefit of fandoms bursting with pent up energy after a pandemic-induced austerity. The re-releases rake up crores in profits – years, even decades, after a film’s first release. Almost everyone we asked said the same thing: fans and their representatives are solely responsible for the recent upsurge in theater activity, including the unexpected profits from old films.

“Fan involvement is crucial in star cinemas in terms of openings, repeat viewings, and benefit shows… They take the revenues to the next level.”

Re-releases are a mutually beneficial arrangement between fan culture and the economics of the movie industry: fans get to relive their ecstatic love for a star, theater owners, distributors, and producers get to keep collecting money on a film that was already made years ago. To claim to be the one who facilitated this intersection, then is no small thing. Murali says it was his idea, when he re-released the old Jr. NTR film Aadi last year. When asked how he does it, he’s vague: “I have a few direct contacts [in the industry].”

The link between devotion and profit has always existed – fans pay money to see their stars on screen. But fans becoming integrated into the business is a relatively recent phenomenon.

Just before RRR released in theaters, one of Tollywood’s most powerful producers and distributors called for a meeting. Murali represented the Jr. NTR fandom and Babu represented the Ram Charan fandom as the Konidela Yuvasena president. The producer was Dil Raju, who was also the distributor for the film in the Nizam area.

There was mutual interest for all stakeholders involved: everyone, including both fandoms rooted for the same film for different reasons – profits, their hero, prestige, and a combination of it all. In order for the film to succeed as everyone wanted it to, fan association leaders were entrusted with the responsibility to ensure that their members behaved responsibly and didn’t hurt box office collections. This meant that their celebrations shouldn’t interfere with those of the other group’s and start a fight.

Every detail was planned in advance: from ensuring both stars had equal numbers of cutouts, equal space for banners, equal perimeter space for fans to celebrate, and equal divisions of seats in theaters. The arrangement was such that Jr. NTR fans would occupy one half, and Ram Charan fans the other. “Fan involvement is crucial in star cinemas in terms of openings, repeat viewings, and benefit shows… They take the revenues to the next level,” says Dil Raju.

Increasingly, fans drive the opening weekend numbers, and benefit shows are a key litmus test. Benefit shows, or special shows, refer to the premiere screening before the official first screening. It’s the 3am or a 4am show before a film’s release that’s specifically meant for fans alone. For instance, Chiranjeevi’s Waltair Veerayya and Balakrishna’s Veera Simha Reddy released at nearly the same time – Sankranthi this year. Their respective fan associations mobilized in competition – trying to ensure that the box office numbers of their star were higher than the other’s.

For RRR, the stakes were even higher: rival fan groups had to cooperate rather than compete. These were two fan groups that, in ‘peacetime’ as it were, constantly fought online over who was the better, more significant star. Did the two fanbases coming together, then, play a role in RRR’s success? “One hundred percent,” says Dil Raju.

But even in cooperation, there was still competition, because everyone had the same aim: profit. In Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, RRR’s benefit shows across 13 theaters in the city were divided along fan lines such that one half of the theaters was occupied by one fandom, the other half by the other. Each group began to compete with the other on how much they were willing to pay to see their hero in the film – the competition constantly trending upwards on the black market, to the tune of nearly INR 2,000 a ticket.

In Telangana, the government introduced flexi-pricing, leaving the decision of ticket prices to the producers. Producers increased the rate. “Once the audience got adjusted to the rates – RRR released. The producers approached the government for higher ticket prices. This had a big impact – though in terms of business it did very well, its audience was lower than Baahubali (the first pan-Indian film helmed by S.S Rajamouli),” says Anupam Reddy, the Telangana Film Chamber Secretary.“Fans think only about the box office [for their hero], and producers speak to fans… they know that if they increase the [ticket] rates, they’ll get their money faster. Fans pay for it.”

This, in turn, according to Bharat Chowdary, the Joint Secretary of the Hyderabad State Film Chamber, means that RRR turned into a litmus test for the performance of every film thereafter. In the absence of ‘star heroes’ in a movie, there’s a high chance it would fail if released in theaters. They then go straight to OTT platforms – making theater releases a space almost exclusively dominated by fandoms.

Reddy says that fan associations even tell distributors where to screen their films and how many cutouts to display, which happens according to what would perform well, in which location.

The Hyderabad Nizam area, for instance, is a Chiranjeevi stronghold. In Andhra Pradesh’s Rayalaseema district, Balakrishna (NTR’s son) reigns supreme. Every theater owner, distributor, and even producer keeps senior fan association members readily accessible – people like Murali and Swami Naidu, who have direct access to heroes, as well. “As distributors, we’re in close touch with fans,” says Chowdary. “Fans sacrifice their lives and live only for their hero. Every other issue is secondary.”

The financial impact of fandom pushed stars to a degree of visibility and success that’s impossible to imagine. Pan-India films – a trend that began with Tollywood films – raised the stakes for every star in the Telugu industry. Fans overwhelmingly crowd out the box office in a bid to push their hero to national success – alienating the “regular” audiences. Post-Baahubali, stakes for fans grew exponentially: a phenomenon that cemented the experience of the cinema as a space for proving devotion through continuous, loud, and visible presence.

The director of both RRR and Baahubali, SS Rajamouli, many say, has his own fan base now that’s bigger than that of the gods themselves. “Rajamouli took their images and multiplied them,” Prasad says. It was true of the actor Prabhas, who turned into a pan-Indian star overnight with Baahubali – and it’s especially true of Ram Charan and Jr. NTR, who scarcely needed a lift individually, but who shot to international stardom together. “If they starred in different films that were released on the same day, fan fights would have been inevitable. It took a director with an even bigger image to bring them together – they both worked hard to make it work. The results show,” K.L. Prasad adds. The plot of RRR itself – or any other pan-Indian film – is secondary. The ingredients of RRR’s success: “two superstars, Rajamouli, and after that the content,” says Dil Raju.

For their part, directors and actors confront a turning point. The taste of stratospheric success created a higher floor for the lows – it’s no longer an option to fail, or one risks losing one’s divinity. As Prasad puts it: “Once [stars] are trapped by the fans’ collective image of them, they can’t do anything else.”

The Successors

In elevating mortal men to divinity, Tollywood fandoms may have landed in a

paradox: they sent their stars too far out of reach. The muscular insistence on box office numbers, rooted in fans mobilizing to prove their worth, is changing Telugu cinema. And it’s a beast of the devotees’ own making. The film industry looks like it’s on a high with RRR – but a closer look at the decision-making processes behind what films get made today shows an existential crisis unfolding. If there haven’t been many new star films in a long time, it’s because there’s now pressure to keep one-upping the previous hit. And with the hits all having been mammoth successes that spanned borders, investing in smaller-budget – or even regular budget films – is a gamble few are willing to take.

“These days, if a film does well in the second weekend, it’s a hit,” says Bharat Chowdary. “Fans are crucial for the huge opening numbers.” And star power, for its ability to draw colossal crowds, equates to money.

Re-release culture, which repurposes movie-star hits for a new generation – or for the nostalgic ones – is a safe bet in this atmosphere. If you ask Murali why he started the trend, as he claims he did, he says that it’s the lack of Jr. NTR films before and after RRR that prompted it. There’s a yearning for more – but more isn’t forthcoming these days.

“We get to see less of our stars now, because the focus is all on big-budget movies,” says Sai Mohan, a Jr. NTR fan. The pressure on larger-than-life stars to deliver mammoth successes means they’re occupied with productions on the same scale. There are thus fewer films for fans to enjoy – and to revel in their hero’s image.

But across fans, distributors, producers, and theater owners who’ve been enmeshed in films for decades, there’s a unanimous feeling: movies have been and remain an essential part of Telugu identity and culture. Since the days of NTR and later Chiranjeevi, a movie star isn’t just an actor – he fills a vacuum for states grappling with who they are, what they want, and their place in history. But the fans are the ones whose devotion decides who heroes are, their place in the world today, and their existence tomorrow.

This took on greater significance in the past year. “Fan devotion has intensified,” says Anupam Reddy. He thinks it’s because of the idleness and unemployment following the pandemic. “After Covid19, people were thankful that they were alive – and thronged again in larger numbers,” Raj said. “[In RRR] two fandoms came together – it’s double the power.”

Wherever the ceiling for Telugu movie stars may lie, the zeitgeist returned to a point where the question of godhood is at large again. If the story of the two dynasties culminating in RRR tells us anything, it’s that the gods are more similar than they are different. And with the existing gods having fulfilled their purpose, other communities may find the time ripe for a new one.

With the bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana in 2014, stars and the identities formed around them have become more complex. Another feudal community that was previously underrepresented in the film industry is now the dominant one in Telangana – the Velamas. The Telangana Chief Minister belongs to this community – but there isn’t a cultural equivalent for Velamas to pin their identity to.

At least, not yet. A new upstart may be on his way: Vijay Devarakonda, the star of the cult success Arjun Reddy, for better or worse signals the arrival of a newer, edgier, youth culture. And leaders from Telangana government, including the chief minister do not shy away to rally their support for Devarakonda, carving out a way to gain cultural capital as a community.

Like his predecessors, Devarakonda is an outsider – a powerful motif. Jr. NTR’s own image has all the ingredients of heroes’ epics that his fandom rallies around, for this reason. He’s the grandson of a cinematic and political titan. And he’s also an outcast – Jr. NTR is an inter-caste child, shunned not only within the family, but also by fans of his uncle, Balakrishna, some of whom don’t see him as the legitimate heir to NTR’s legacy. For his fans, this is part of the appeal. “We watched him struggle in his own family as an outsider. As the son of his father’s second wife, his family distanced him. Still, he succeeded despite that. That makes us admire him even more,” said Nagendra Kumar, the fan who works closely with Murali and makes charity donations in Jr. NTR’s name.

Now, even as the future of an authentically Telugu cinema remains unclear, a unanimous sentiment echoing across all fandoms will decide, as always, what it’ll look like. It’s what Murali ends our conversation with: “We’re willing to do anything for our heroes. Anything.” For people who are willing to give their time, money, and even blood in the names of their stars, who have only been men for decades, the only thing they receive in return is the gods’ acknowledgement. Most fans would argue it’s enough.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii. Divya Kandukuri is a writer whose work lies in the intersections of caste, gender, pop culture and mental health. She's the founder of a Phule-Ambedkarite mental health collective, The Blue Dawn. Currently she works as a senior projects associate at Zubaan.