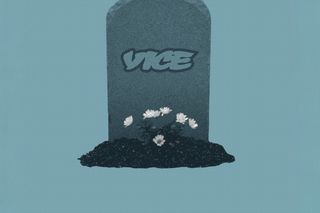

Vice Is Dead

Why indie media is in such rapid decline.

“Publishers, brace yourselves—it’s going to be a wild ride,” The New Yorker quoted Matthew Goldstein, a media consultant, as having written in a newsletter last month. “I see a potential extinction-level event in the future.”

Yesterday, Vice announced hundreds of layoffs and the closure of its iconic site, Vice.com. This is, for all intents and purposes, the final nail in the coffin for what The New York Times called a “digital colossus” that was already in its death throes: last year, after closing its Vice World News division, the outlet filed for bankruptcy.

This comes after Buzzfeed News shut its doors last year, and several other smaller digital media outlets – some crucial for cultivating a sharp, subversive tonality in the Internet age – like Jezebel, Gawker, Bitch Media, Wear Your Voice, all announced closures as well. Plus, some of the largest conglomerates are in dire straits too: Condé Nast and Vox Media both announced significant layoffs last year and this year. It’s all unprecedented – with experts calling the magnitude of media layoffs across the board in particular “breathtaking” – and we’re well past an existential crisis. We’re already in an extinction crisis.

How did we get here? Well, for one, digital media’s reliance on the Internet proved to be its downfall. Consider the business model for all of them: traffic generates greater ad revenue, and every click mattered. The etymology of “click-bait” should tell us something: clicks ensured not just growth, but survival, making them a cornerstone of the digital media world. It’s the reason Buzzfeed pioneered its style of traffic-generating engagement bait, like quizzes and listicles, while also investing in hard-hitting journalism. And as it happens with every valued commodity, guerrilla-style mass media eventually gave way to the click-inflation: the more of it you amassed, the more your value diminished. "I think the free model -- trying to build high volume, and then sell ads on that basis -- hasn't worked out nearly as well as hoped," said Rick Edmonds, a media business analyst at the Poynter Institute, a non-profit journalism research organization.

The venture capitalists who funded the new digital behemoths gradually lost interest. As interest rates rose, “everybody called in their chips,” explains Aileen Gallagher, chair of digital journalism at Syracuse University's Newhouse School of Public Communications.

That’s when Buzzfeed went public – and suffered for it. To add to that, everyone was – and still is – dependent on private tech platforms whose bottom line ultimately trumps anyone else’s. Facebook and Google were essential determinants of traffic – while simultaneously being competitors for ad revenue. Now, Facebook has stopped promoting news articles and Google has begun to develop AI integrated search to keep users in the ecosystem, rather than migrating away to specific sites. And X, formerly Twitter, is going through its own implosion, thanks to a mercurial CEO who made a series of decisions that turbo-charged an ongoing misinformation pandemic, making news less reliable than ever. “[We were] slow to accept that the big platforms wouldn’t provide the distribution or financial support required to support premium, free journalism purpose-built for social media,” Jonah Peretti, Buzzfeed co-founder, said in a staff memo announcing the closure of Buzzfeed News.

Moreover, as tech journalist Charlie Warzel pointed out, it isn’t just big bad tech and CEOs – even readers have quit digital media. A Pew Survey shows that more people rely on influencers and podcasters as sources of news and information than ever. Another Reuters survey showed that consumers are now making a cost-benefit analysis of subscribing to digital media versus digital entertainment. And streaming, it would seem, is winning this tug of war.

"I think the current moment is the product of both a huge shift away from social media, and a tough economy," Ben Smith, a former editor in chief of BuzzFeed News and author of

‘Traffic,’ a history of the rise and fall of BuzzFeed, told NPR. And for smaller, truly indie publications – many of which were radical and feminist – the existential choice was to stay reader-funded and thus underpay writers, or accept ads from companies that didn’t align with their missions and alienate readers. In other words, it was an impossible choice.

While numerous reports trying to make sense of it all have tended to focus on the failing business models, the lax company executives helming media outlets (as Intelligencer put it,

“The worst people are dancing together on the lip of the volcano as the journalists fall into the caldera.”), the social media-news nexus, and readers’ fatigue and distrust, there’s a deeper, systemic factor underlying all of it: the privatization of the Internet as a whole. The Internet – once a digital commons, born out of public money – isn’t as democratic or malleable to public opinion as it appears to be. In fact, quite the opposite: guided by the logic of enclosure under capitalism, private tech companies seized digital space and servers in order to monetize it. In a sense, this is merely the extension of what has been taking place for centuries: first, it was the enclosure of land which ushered in the age of private ownership and capital in the “real” world, sifting and separating people into classes depending on their relationship with said capital (whether they owned it or worked for the people who owned it). Then, this extended into the digital, even if it doesn’t look like it. Instead of mining our labor, private owners of digital space mine our data. It’s what the scholar Shoshanna Zuboff called “surveillance capitalism” – wherein our data and attention is harnessed via technologies which monitor where and how we place our attention.

And this applies to the news too. By owning the platforms where the news is proliferated, tech companies have created a near-feudal relationship, where digital media almost found itself beholden to digital landlords in order to survive. "Venture capitalists told themselves a fairy tale, which was if Vice and Buzzfeed News and all the rest are going to generate this much traffic, there must be a way to monetize all that traffic,” says Dan Kennedy, a professor of journalism at Northeastern University in Boston. "The news industry didn't really have a profit model other than trying to get eyeballs and earn digital advertising revenue," Courtney Radsch, who studies technology and media at UCLA, told NPR, adding, "But what we saw is that the tech platforms, specifically Google and Facebook, ended up controlling that digital advertising infrastructure."

By design, then, digital media seeking to stay afloat found itself competing with individuals who monetized themselves on the platform: influencers. This prompted a shift in consumption patterns away from trust and towards parasocial relationships – which is also why journalists found themselves having to heavily self-promote on the same platforms that eventually decimated their workplaces. “It’s a whole combination of things, and everywhere you look there’s a different factor… Social platforms are, generally speaking, not places where you can build a business,” said Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, told The Guardian. And as Slate put it: “If the original sin of the digital economy was to make the news free, the proposed fix—to trust that virality alone could drive readers to important subjects—was far from a cure.”

Indeed, the structural conditions of digital platform capitalism ensure that everyone who ever uses them for the purpose of mass communication is a brand unto themselves. This arguably proved to be a self-fulfilling prophecy for digital media: once forced to drive “engagement” through click-bait and listicles, these were the very facets of digital journalism that prompted fatigue in the brand. And it didn’t help that once online, strategies for news-gathering also became heavily dependent on what was going on in these platforms. Just take, for instance, the fact that at the time of writing this, a 50-part TikTok called “Who TF did I marry?” has become newsworthy enough to be reported by The Cut, Time, Huffington Post, and more. It isn’t that the TikTok isn’t entertaining – it’s that entertainment, slowly and surely, became news. This, despite the Reuters survey showing that entertainment is crowding out the news. "Users turned away from news on social media. And then the platforms, seeing users turn away, starting pushing news out," Smith added.

With a dismal future looming large, many have begun to wonder what the future of digital media will look like. Some seem to think that it’s in tech. “‘Netflix spends a billion dollars in R. & D.,’ the former [LA Times] executive told me, largely on data scientists, engineers, and designers who help users discover content they’ll love. Newsrooms might also need to approach the problem in a more methodical, tech-driven manner,” Clare Malone reported in The New Yorker. Tech killed digital media, but tech might just be our last hope to resuscitate it. And if that’s the case, we’re doomed to repeat the same mistakes, unless the root of the problem is addressed. Ultimately, it also comes down to who owns the tech too. As Bell added, “Being squeezed by private equity is an ugly place to be because it has no commitment to making media sustainable.” Even legacy media is struggling: currently, The New York Times is kept afloat by cooking apps and games.

But others aren’t so sure. "It took 150 years after Gutenberg before anyone thought to invent a newspaper. I think we're talking about decades, maybe even generations, before we figure out this next stage," Jeff Jarvis, a media critic and a journalism professor at the City University of New York, said. Vice, for one, is looking to explore a studio model of business.

Meanwhile, Indian media is in freefall for different, but not unrelated reasons. Newspapers are in decline, as a Newslaundry analysis shows. Amid declining press freedom and tightening regulatory controls over digital media, it remains to be seen what the future of sustainable digital media – one which pushes boundaries rather than complies – will be. But the fingerprints of these original upstarts – the ones who went to document life in the Taliban, exposed China’s mass detention of Uyghur Muslims, and also pumped the Internet with quizzes about which rug a celebrity looks like or crowdsourced frat stories – are everywhere, and they’re indelible. They speak to a media culture that blurs the distinction between what’s important and what’s relevant and asks, what’s the difference? In other words, digital media is dead. Long live digital media.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

.png?w=320&h=320&auto=format)

Hungry For Education