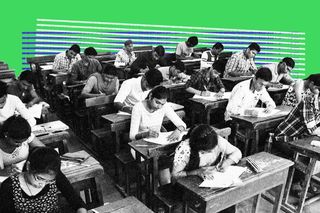

Why a Common Entrance Test for University Admissions May Harm Students

The test may not necessarily be in the best interest of all students and restrict access to education even further.

The National Testing Agency (NTA) announced on Tuesday that central universities will now be required to consider scores from the Common University Entrance Test (CUET) for admission, instead of the traditional 12th–grade board exam results. UGC chairman M Jagadesh Kumar said that the application process for the same will begin in April, with the aim to begin tests by July. Kumar added that the endeavor is to ultimately reach the goal of “one nation, one entrance test.”

While it remains to be seen what the impact of the move will be, there are precedents to show how it may not necessarily be a good one. For one thing, it would further diminish the relevance of schools and the different pedagogical practices across boards. Second, homogenizing an entrance test would make access to higher education difficult for students from marginalized backgrounds without the means to avail of coaching classes or extra resources that normally provide an advantage to their more privileged counterparts.

On the other hand, stratospheric cut-off expectations from universities may now be obsolete — Delhi University’s 100% score cut-off was the most recent and controversial decision that sparked conversations about access to education. However, in a socio-cultural landscape rife with vast inequalities, a common entrance examination would increase competition and ensure educational access to those who can afford to spend the most time, money, and resources in training for the exam.

Related on The Swaddle:

There Is No Such Thing as Achievement Through Pure Merit

The idea speaks to the general nature of competitive examinations in India, and the harmful impact they’ve had on young learners. The most notorious example of the same, of course, is the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) for entry into the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs). Coaching for the JEE begins at a young age — and as the competition increases, children are made to train for the exam at ever-younger ages. Coaching institutes, moreover, are prohibitively expensive and are a drain on students’ creativity, freedom, and self-expression, as all identity or even learning is geared towards securing a seat in a college. It’s why places like Kota, Rajasthan, are known for their worryingly high suicide rates.

The National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) for admission into medical undergraduate courses in India is another notorious example. The test has been a point of contention for a long time now; with ongoing petitions seeking to dismantle it altogether. The issue came to a head with the suicide of NEET aspirant Anitha, in Tamil Nadu, who was from a poor family and attended a Tamil-medium school. Following this and a spate of other suicides, an expert panel suggested that NEET will actually harm healthcare rather than bolstering it. In their report, the panel also invoked B.R. Ambedkar, who said, “examination is something quite different from education, but in the name of raising the standard of education, they are making the examinations so impossible and so severe that the backward communities which have hitherto not had the chance of entering the portals of University are absolutely kept out.”

“Moreover, students believe that not only will richer candidates have an unfair advantage but students who were already preparing for standardized entrance examinations — like the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) for engineering aspirants or National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) for medical science aspirants — will have an edge over students who were solely focusing on preparing for their boards until the exams were canceled earlier this month,” Devrupa Rakshit noted in an article earlier.

Related on The Swaddle:

Further, a collapsing public education system may not have the wherewithal to train students for a common entrance test where they would compete with students from private schools that have better resources. “Increasing privatization today further ensconces education for the elites and sorts children based on casteist notions of inherent ability. National policies preserving the public-private divide and depoliticizing education into merely a rung in the ladder towards job markets stand in the way of education becoming something more,” wrote Rohitha Naraharisetty in The Swaddle last year.

EdTech firms are swooping in to offer themselves as democratic solutions to inadequate school education, but these can be expensive too. They also capitalize on fears over the Covid19 “learning gap” to sell more products without actually offering meaningful solutions to the education divide in India, as Saumya Kalia noted in a piece for The Swaddle earlier this month. Common entrance tests may bolster this tendency, making education more inaccessible.

Overall, experts have noted for a while that common entrance tests stand to widen the socio-economic gap among students in India. The introduction of the CUET all of a sudden with very little notice leaves no time for students to familiarize themselves with what to expect from the examination, and once again disadvantages marginalized students and first-generation learners without the networks or contacts to understand and learn more.

Keeping marginalized students out is not only harmful to the students themselves, it also impacts the quality of institutions in the country. When only caste and class-privileged students are offered access to education and jobs, their perspectives are overrepresented in facets of life that affect everyone. Fair representation is thus key to ensuring the health of a country’s overall development and prosperity.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

After Actor Bhavana’s Sexual Assault Complaint, Kerala Mulls Law for Protecting Women in Cinema