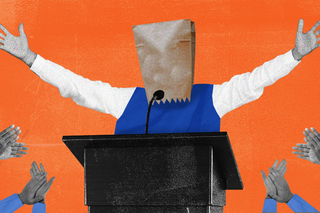

Why We Believe People in Power, Even When They Lie

People want to believe that someone is telling us the truth — even when the context suggests falsehood.

When former U.S. president Bill Clinton so famously said “I did not have sexual relations with that woman,” the world, even for a moment, believed him — until the whole story came out. Another member of this league of presidents, Richard Nixon, claimed he was “not a crook” after the Watergate Scandal. In 1994, the CEO of a popular cigarette production company in the U.S. said “Cigarette smoking is no more ‘addictive’ than coffee, tea, or Twinkies” — in a bid to assure people that cigarettes are neither unhealthy nor addictive.

The thread of fabrications runs through history — uniting politicians, entrepreneurs, celebrities, any person remotely in a position of authority. It presents a baffling notion: why do people go above and beyond to credit falsehoods when it comes from people in power? One may be tempted to believe it’s the increasingly grey area between fact and fiction that makes it hard to identify lies. Or maybe people are just insensitive to false claims; maybe they no longer care what is true and what is not.

The reason we’re willing to believe people in power cuts across psychology and socio-political contexts. It’s important to realize lying — irrespective of it existing as a stain on morality — is all too common; people lie all the time. An average person may lie about twice a day; prolific liars may tell as many as five lies in a day. Former U.S. President Donald Trump himself is famously credited for making more than 30,000 false claims during the tenure of his presidency; to put that into perspective, that’s an average of more than 20 lies in a day.

Despite the ubiquity of tall tales and canards, the problem with lies when it comes from people in power is simple. Falsehoods can easily and efficiently influence — and shape — people’s thinking even after someone realizes the information is false.

What makes us gullible to false statements from powerful people? For starters, human bias. “We have a bias towards believing what we hear is true and make judgments on that basis, even when the context suggests the information is likely false,” wrote author Cass R. Sunstein, a professor at Harvard University. Sunstein, who wrote the book Liars: Falsehoods and Free Speech in an Age of Deception. Sunstein refers to our innate “truth bias,” which goes on to explain why people would still rely on false information to make value judgments. We seem to trust people “even when we should not.”

The root of the problem lies in something called “meta-cognitive myopia”; that people seem alert to pick on “primary information,” like the claims of a politician that they helped a struggling community during a health crisis. But more “meta-information,” one that would help them detect whether this primary information is true in the first place, seems to be lost on us — fueling a truth bias.

“In hunter-gatherer societies, survival often depends on how people react to the evidence of their own senses, or even to signals that they receive from others. If you see a tiger chasing you, you had better run. And if your friends and neighbors are running, it makes sense to run too. There is much less urgency to picking up on signals about whether those signals are reliable,” Sunstein explained. Our default assumption then is most people are telling the truth — even if the context paints a different picture.

There is also some research on power and trust to show that people in lower positions of power are more likely to believe others. This is because people harbor hope “that their exchange partner will turn out to be benevolent, which then leads to their decision to trust,” the researchers wrote. “In sum, the decision to place trust seems to be based more on one’s motivation to protect oneself from unwanted realities than on relatively rational calculations of the other party’s deliberations.”

What makes falsehoods also believable is the absurdity of a lie in the first place. “It’s very complicated, the way we process information,” said Ron Riggio, an organizational psychology professor at Claremont McKenna College speaking broadly about the nature of lying. “It’s the politics of audacity. The more outrageous and audacious the lie is, the more people say ‘that’s got to be true because why would someone make something like that up?'” Think especially in terms of elected governments in charge of people’s well-being and social welfare: why would elected officials mislead billions of people? In December last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi valiantly claimed Goa came under Portugal’s rule when other parts of the country were ruled by the Mughals. This is as good as fiction — for Portuguese rule in Goa began in 1510 while the Mughal rule started in 1526.

Related on The Swaddle:

How ‘Political Gaslighting’ Undermines the Truth

It is also the socio-political context of a society that makes false claims easily digestible. In 2018, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University outlined thecircumstances of what makes people believe politicians’ or even a “lying demagogue’s” lies. When people feel left out from a political system — when the overwhelming feeling is one of being disenfranchised and thinking no one cares about their interests — they may gravitate towards these self-proclaimed “champions of people” who weave interesting tells of “self-sufficiency” and the “power of the common man. “Under those specific circumstances, flagrant violations of behavior that is championed by this elite – such as honesty or fairness — can become a signal that a politician is an authentic champion of the ‘people’ against the ‘establishment,'” the researchers noted.

In 1919, General Paul von Hindenburg told the German people the reason Germany lost World War I was because “radical” people in the country wanted to replace the monarchy with a republic. “The German army was stabbed in the back,” he famously said; concealing the real reason for the defeat which was that the army was overpowered on the battlefield. The effect was powerful: Germany would rise to greatness if these radicals could be reigned in. The lie, as Readers Digest noted, eventually fueled the rise of the Nazi party.

A dossier of lies and falsehoods can also be found closer to home when the Union and state governments have repeatedly misrepresented truths. I go back to the political philosopherHannah Arendt’s words, who so aptly made the crisis of trust evident: “no-one has ever doubted that truth and politics are on rather bad terms with each other.”

Related on The Swaddle:

When You Lie, You’re Likely to Think Others Are Lying, Too

This brings us to another reason why people may want to believe someone powerful. It is when the person is emotionally or psychologically important to them, it becomes easier to believe their claims. It’s not as if people blatantly disregard facts; but that their intellectual proximity shapes people’s trust. One research published last month showed this instinctive desire to believe also guides the person’s voting interests. While labeling a claim as a lie led to people being disillusioned with it, it did not “necessarily translate into a reduction in voter support or a change in voting intentions,” the researchers noted. In other words, people knew a politician was lying, but that did not change their patterns of support.

In some ways, a desire to believe a powerful person’s falsehoods often brings people ideological succor too. According to a study, people were more likely to let a leaders’ lies go under the radar if they could imagine a scenario where the said lie could be true — this was if the lie aligned with people’s outlook of the world. To show this, the researchers displayed false claims made by U.S. politicians to some 3,000 people and asked them how unethical it was to make these statements. Some were asked to think about how a certain lie could have been true. Interestingly, this meant that lies that came even a little close to reality were discounted by people and were perceived as less dishonest, because they could have been true in an alternate case. For example, when former U.S. President Donald Trump claimed his inauguration ceremony in 2016 had an “unbelievable, perhaps record-setting turnout” – but he didn’t.

Human nature — coupled with the rampant misinformation, political gaslighting, and authoritarian behavior — spell a morbid era for truth and its arbiters. But that does not mean that people have given up on honesty or from holding powerful people accountable. The 2018 research that looked at socio-political contexts also spoke of a world where people would actively resent untruths: it is when they would perceive the political system to be fair, accountable, and inclusive, that they would outrightly reject dishonest people in power.

We live in a world of half-truths, shades of grey, and warped narratives of reality. The fabric of today is dynamically spun by people on a pedestal; to recognize the shades of falsehoods is a start to separating fact from fiction.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

How Photographs Influence Our Memories