As Met Gala Romanticizes the Past, Abortion Rights Face the Most Urgent Threat in the U.S.

There is something disorienting about watching “gilded glamor” co-exist with the regressive standards for human rights that prevailed then and do so now.

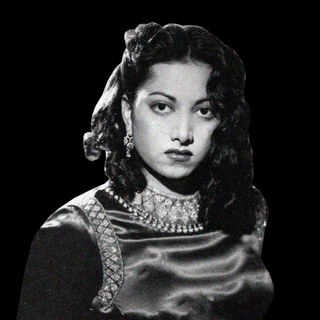

The evening of May 2nd, 2022, is one of striking contradiction; it tells a tale of time past and present. Elevated on the side of New York’s Central Park was a celebration of the oppressive wealth of the 19th century. Sparkling gold gowns come bedazzled with Marlyn Monroe’s memory; someone came dressed as the Statue of Liberty; there were corseted bodices paired with satin gloves and silk trains that took on a modern aesthetic. The Met Gala of 2022 was one in honor of America’s Gilded Age; a hat tip — even a bow — to the fashion that co-existed with the churn of industrialization and the dawn of capitalist society.

Almost simultaneously,news breaks of the U.S. Supreme Court voting to strike down a landmark abortion rights decision. “Roe v. Wade was egregiously wrong from the start… I pray the [Court] allows the states to once again protect unborn life,” one conservative politician wrote in a draft policy. Roe v. Wade is something of a cultural and social monolith in the United States; the 1973 legislation guaranteed federal constitutional protections of abortion rights and has largely been viewed as a cornerstone of protecting women’s bodily autonomy, privacy, reproductive rights, and well, their humanity.

Wealth inequality coated in fine varnishing of luxury lies towards one side. A screeching death of reproductive freedom in one of the oldestdemocracies of the world fights for space on the other. The dichotomy is absurd at best, disorienting at worst, and a piercing saga of our reality overall. In one night, we seem to have regressed centuries.

But why does this particular moment in time feel unnerving? Wealth preludes the existence of inequality; during the pandemic itself, those marginalized grew poorer as rich people emerged richer. The theme is a good hint; this gala of the rich celebrated “gilded glamor”; economic growth, industrialization, all the buzz words. The riches of the yesteryear co-existed with a disregard for human rights always, something that we seem to be echoing even today. This was a time of the “robber barons” and new money: at the expense of child labor and the labor exploitation of people of color. This was also a time when reproductive rights were just beginning to take shape but women’s rights remained largely absent all over the world. By the 1880s in the U.S., as women and partners gained access to safer methodsof contraception, contraception and abortion came under legal restrictions.

That a similar fate may play out for millions of Americans unexpectedlyharkens back to the past. At the Met Gala, the former secretary of state Hillary Clinton came in a dress embroidered with names of “gutsy women” of the 19th and 20th-century liberation movements. The celebration of women’s empowerment over the years feels shallow and tone-deaf at the same time the country’s highest court of law ideologically opposed nationwide abortion — a touchstone and legacy of the women’s liberation movement.

Related on The Swaddle:

Everyone Laughs at Met Gala Costumes, but Not Gen Z and Not This Year

Arguably, wealth disparity is deeply tied to abortion rights; class inequality makes reproductive freedom “a province of the privileged rather than a power shared by all people,” as Ken Estey pointed out. It is disproportionately poor women of color whose access to abortion is and has always been most at stake, leading to potential fatalities. A study conducted in December 2021 showed how “state initiatives to restrict abortion could lead to more deaths, particularly among Black women.” When we celebrate the Gilded Age at a time of burgeoning inequality and inflation, it is deeply connected to women’s lives and reproductive autonomy. “The link between the denial of abortion rights and adverse socioeconomic outcomes is not unwanted but actually expected, if not deliberate,” Estey added.

The celebration then does not only romanticize outrageous displays of wealth of the 19th century, but also the regressive standards for human rights that prevailed then and now. Wealth disparity and un-freedom — two systemic issues, two time periods, one overarching sentiment.

Overall, the irony is piercing. “Gilded Glamor and White Tie” juxtaposed with worsening inflation most Americans, and the world, are dealing with. One user tweeted: “Am I the only one who thinks this years #MetGala theme is out of touch? inequality is at the highest levels since the Gilded Age, a pandemic & economic meltdown wrecked us, inflation is out of control … but cool, let’s wear #GildedAge themed dresses & laugh about inequality … this year’s theme is a slap in the face to average Americans.”

Some costumes from this year as well served as reminders; some paid ode to America’s transit system, some to the struggles of the working class and immigrants. But the visual of corsets and elevated trains not only harkened back to a time of monetary glory, but also a time of disempowerment. Fashion is always political; then what do we make of this “revolutionary” aesthetic of fashion that feels light-years away from reality?

The muckiness lies not in the fact that people raised glasses to “gilded glamor” on the same night that women’s rights across the country lay besieged; but that the past and present carry a resemblance so bleak and real. We may be more than a century into the future, but our vision of human rights and autonomy took a sudden leap back into the past.

Perhaps, this is the Gilded Age, if we go by authors Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner’s definition. Gilded meant not golden, but a sheen so superficial that it was just the right kind of shiny to hide the rot within.

No one puts it better than author Bess Kalb, when she says: “Let this be remembered as the night the Met Gala saluted the Gilded Age, a time of outrageous wealth disparity coated in the patina of luxury, while the Supreme Court sentenced poor women seeking reproductive freedom to death.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Can We Move On: From the Trope of the Man Whose Violence Is Justified Because His Partner, Sister Was ‘Wronged’