What Pop Culture Misunderstands About Serial Killers

Whether it is homophobia or misogyny — serial killing is rooted in cultural anxieties that society brushes under the carpet, which eventually manifest in horrific forms.

“We serial killers are your sons, we are your husbands, we are everywhere. And there will be more of your children dead tomorrow.” These were the words notorious serial killer Ted Bundy left the world with some time before his execution. As much as it discomfited an already chilled audience, the warning carries a truth that we are perhaps still not ready to confront as a society.

Serial killing – long considered to be a horrific exception to a peaceful norm – has held society’s aspirations and optimism in a vice grip of fear and nihilism. The media we consume about killers reflects this: reams of pages and reel have been dedicated to understanding just how and why this happens. For it is a shocking thing indeed when a single individual shows capacity for a violence so extreme, so sadistic, that it defies all understanding of the human condition.

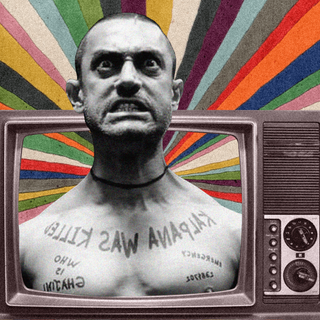

We’re oversaturated with film and TV about serial killers — real and fictional. Recently, the John Wayne Gacy Jr tapes were released as the second installment in the Conversations With a Killer series on Netflix. But like most other true crime media, the docuseries only focuses on the individual as a depraved, perverse anomaly of his time. There are hints of a broader cultural context of the 70s: the sexual revolution that characterized more sexual freedom for women and young queer people, who were now asserting their identities in public. This triggered a feedback loop of homophobia and destitution in society, making young queer people vulnerable to violence. Although the series explains how John Wayne Gacy was able to operate the way he did, it does little to explore how the man himself was a product of the cultural anxieties of his time. He was very much the status quo, mutated and distorted into a nightmarish form of the violence already implicit in society.

John Wayne Gacy assaulted and killed young boys and men, hiding their bodies under his floorboards. This last has stood out for the way it disturbingly – but aptly – metaphorizes what American society did to its queer youth in the same period. By brushing an emerging culture under the carpet, the systematic apathy from all of society was complicit in the murders.

Ted Bundy was the subject of the first installment of Conversations With a Killer; Jeffrey Dahmer may be the next. Dahmer was known to have sexually assaulted, killed, dismembered, and even cannibalized young boys and men. Bundy reportedly did the same with young college-going women. Bundy and Gacy were “active” in nearly the exact same time period; Dahmer, on the other hand, picked up where they left off. But the 70s, 80s, and 90s were also decades marked by parallel shifts in the American zeitgeist: bookended, on the one hand, by the women’s liberation and the civil rights movements; on the other, by the rise of the AIDS epidemic and the end of the Cold War. “Family” values and the overall shaky stability on which many oppressive ideologies – white masculinity, most of all – rested were under an irreversible churn.

Amid all this conflict, violence was a recurring undercurrent that represented the nation’s hostility toward those trying to break free of its supposed values. And yet, many of the most popular shows about serial killers from the time focus overwhelmingly on individuals.

HBO’s Mindhunter, for example,explores how the genesis of the term “serial killer” occurred in the late 70s, when the FBI began to analyze the psychological profiles of notorious serial killers to understand how theywork. The idea that they followed a pattern of violence to keep killing earned them the title; but while the series offers an inside look at how the police uncovered cases by looking at the minds of killers, what of the nerve centers of society itself that prompt the violence of the killings?

The genre, as a whole, forgets that serial killers operate within a culture of violence and bigotry already; their acts may be exceptional, but the rationale isn’t. Whether it is homophobia, misogyny, or sadism — it all has roots in the cultural anxieties that society brushes under the carpet, which manifest eventually in horrific forms.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Do True Crime Stories Fascinate Us?

Story after story has focused on the psychology of serial killers – studying their minds to look at their childhood, their brain circuitry, poking and prodding to desperately search for something that can allow us to settle down into a bubble of peace once again. Even more unbearable to confront than the violence itself, is the fact that it may have been a product of the very society governing us.

Beyond the psychosis, psychopathy, and other such conditions that experts often explore as root causes lie unequal systems of power, state neglect, and fractured aspirations of a promised life.

“I don’t think people are born evil… I think that if any one of us was treated the way these individuals were treated as children, and if we had the same vulnerabilities to psychosis, or if we had brain dysfunction, I think sure [everyone has the capacity to kill],” Dorothy Otnow Lewis, a psychiatrist, told Vice. Lewis is known for having spoken with serial killer Ted Bundy the day before his execution to find out why he brutally assaulted and killed over 30 women.

Some of the easy answers that media resorts to involve psychology and the brain’s primordial limbic system being more active in some than in others. Mindhunter dedicated two seasons to understanding how serial killers think, what drove them. In the process, it uncovered the fact that we can’t stop looking at and thinking about what they do because it represents a part of our own minds that we suppress: the Freudian id, the scene of all our darkest fantasies, the Hyde lurking within.

It is the “rational” part of our mind – the ego – that keeps us in check. We abide by laws, by inherited ideals of morality, and perhaps have an innate sense of “goodness” to thank for the fact that the streets aren’t overrun by killers on the loose every second day. But we need to acknowledge the fact it is this very organization of society within which serial killers play out their grisly fantasies – and this is the crux of the dilemma. Serial killers play at the heart of the tension between civilization and savagery. In effect, however, they complicate this binary by showing how savagery lies in the dark heart of civilization itself: indeed, the rules, codes, and norms we make for ourselves and live by have no meaning without the violence and bloodletting.

David Fincher’s Seven, the chilling story of a serial killer motivated by the seven deadly sins in Christianity comes close to exploring this tension. The tale is a chilling echo of how early imperialists often justified their plunder, genocide, and occupation of colonies as a “civilizing mission” to spread the word of God to “savages.” In Seven, John Doe is someone who aims to right the wrongs of the world through violence and a fatalistic, dogmatic faith. And in the end, he succeeds in even turning the quintessential “good cop” over to his side.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why People Are So Creeped Out by Clowns, According to Science

The problem, however, is that like most other media in the genre (Zodiac, The Pledge), the police are venerated as the trusty do-gooders fighting evil. While Seven dilutes the difference between cop and killer in the very end, it does so as a consequence of the cop’s disillusionment and experience of violence. More often than not, however, this line is already blurred from the start; police exercise unjustified violence on ordinary citizens just to uphold their favored status quo. Indeed, even the origins of the police as an institution itself has its roots in colonialism and slavery. In real life, they are less superheroic upholders of “good” so much as ordinary. And the ordinary is often disquietingly violent.

In a way, serial killers then form an integral part of society’s structure and help justify it: they give cops a reason to exist, for cops to make use of violence legitimately. The cops then close the feedback loop between state disciplinary violence and enforcement of civility. But what civility means has always been defined by the powerful: by white, Christian, cis-het men, at the intersection of patriarchy, cis-heteronormativity, white supremacy, imperialism, and capitalism.

Perhaps the most frightening thing about serial killers, then, is that they aren’t uniquely grotesque bogeymen from our nightmares; they are just the manifestation of what our culture constantly whispers into our ears – about women, about deviance, about sex, about bodies, about freedom itself. When serial killers reigned supreme in the United States, it corresponded with greater freedoms in terms of racial integration, sexual mores, and women’s autonomy.

“Starting in the 1970s, the image of the good life as an economic good life started losing its traction,” said philosopher Lauren Berlant. She adds that a “cruel optimism” lulled people into a false sense of security about the world they lived in – even as many of their freedoms and indeed, their opportunities to live, were being eroded by the state-corporate nexus.

And this, perhaps, is what makes serial killer genres so captivating to consume: there is the usual morbid fascination, but there is also a primal nudge in our subconscious, telling us that these individuals are the missing link between what was promised to us about the good life, and what we got instead.

If serial killers exist, it is because violence existed far before they ever did, and outlives them in the form of destitution, death, neglect, and systemic marginalization. Zooming out to look at the big picture shows that serial killers make up a very small percentage of deaths. It is easy to put down madness and evil to individuals because it helps us ignore the fact that the police, the military, and the corporations serially kill the very people they are meant to – or claim to – serve, everyday. These are all rational acts of murder committed to uphold the status quo of upper-caste and white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity.

It’s why there is so often an implied element of deviance and perversity associated with serial killers that is not unlike how sexual minorities – or the sexual mores of minority communities – are treated by the mainstream. It is far easier, therefore, to relegate serial killers to one of two categories: crazed, irrational beasts with mental illnesses or cold, calculated perverts. One stigmatizes mental illness, the other stigmatizes sexuality – but both divert attention away from the fact that the killings are merely unusual forms of a usual kind of violence.

“Our Billy wasn’t born a criminal, Clarice. He was made one through years of systematic abuse,” notes Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of The Lambs. The missing link is that this systematic abuse is often fuelled by the very heroes of these stories – and the institutions they stand for.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Woe Is Me! “People Confuse My Awkwardness With Arrogance. How Can I be Less Off‑Putting?”