Census 2021 Will Not Include Caste‑Wise Data Despite Demands From Activists, Politicians

Some experts argue that enumerating caste has the “potential to be the beginning of the end of caste.”

The Union government on Tuesday noted that the upcoming 2021 census will enumerate only Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) to chart India’s caste-wise population. The data will not include Other Backward Castes (OBCs).

Previously, anti-caste activists, as well as the state governments of Bihar, Maharashtra, and Odisha, had requested the central government to consider a comprehensive caste-based census.

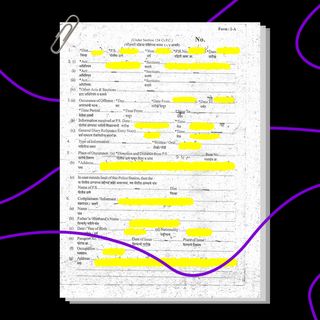

“The government of India has decided as a matter of policy not to enumerate caste-wise population other than SCs and STs in census,” Nityanand Rai, the Union Minister of State for Home Affairs, said in the parliament this week. Under the current policy, the castes and tribes that are specifically notified as SCs and STs in the “Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order,1950” and the “Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950” are enumerated.

The Union government has, several times in the past decades, denied appeals to carry out census along caste lines citing “practical difficulties that may affect the integrity of the headcount.” Among other things, the fact that part-time enumerators (mostly school teachers) are not trained to collect detailed caste-based information poses a major logistical challenge according to them.

Different ruling governments have also stated that including caste in the census has the potential to inflame social tensions within castes and further entrench caste-based politics.

However, many activists argue that caste-based census data could actually reveal the extent to which society’s casteism disadvantages people. “People should know how upper-caste hegemony has kept a majority of the population out of the ambit of prosperity, development, education, almost everything that a civilized nation should offer to its people,” Sharad Yadav, a politician who has been advocating for caste-wise data on the Indian population, said in 2018.

Related on The Swaddle:

Casteism Still Thrives in Elite Schools in India. What Would Anti‑Caste Education Look Like?

Moreover, activists note that enumerating different oppressed groups can help devise better policies to address the socio-cultural challenges. “There is a belief that including caste data in census enumeration will perpetuate the caste system and defend social divisions,” Professor Ravivarma Kumar, a senior advocate and constitutional expert, wrote in 2000. “In fact, not including caste data would perpetuate the injustice of the caste system because lack of data will render inefficient policy measures meant to help the weak,” he noted.

A major argument in favor of caste-wise enumeration is that in a society where caste is at the root of discrimination and inequality — in healthcare, education, and even access to justice — it’s important to monitor how it affects people in order to devise ways to address its impact. Excluding caste-wise data will not erase casteism, but including it has the “potential to be the beginning of the end of caste,” a researcher argued.

“[C]ensus enumeration would yield a wealth of demographic information (sex ratio, mortality rate, life expectancy), educational data (male and female literacy, ratio of school-going population, number of graduates), and policy-relevant information about economic conditions (house-type, assets, occupation) of the OBCs,” an article by The Print reads.

“This information can go a long way in evolving and fine-tuning evidence-based social policies. This could also bring down avoidable street fights over which caste should or should not get reservations,” it added.

Activists argue that in order to ensure the benefits of reservations truly reach people it’s meant for — and actually benefit them — it is important for policymakers to have data on the socio-economic hurdles different segments of the population are facing, and to what extent it impacts their lives. And caste-wise census data, according to them, is one of the best ways to assess that.

The last time data on caste was collected was pre-independence in the 1931 census — when India’s population included that of present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. The population has grown from 270 million at the time to 1.38 billion now. The commissioners of such census have noted the importance of understanding caste as a distinguishing feature of an “individual’s official and social identity.” But caste as a marker was halted after independence — “to help smooth the growth of a secular state,” according to Reuters.

Related on The Swaddle:

By Stifling Marginalized Voices, Social Media Mimics Real Life Casteism

According to the Rohini Commission, which was formed to look into equitable redistribution of the 27% quota for OBCs, noted that there are around 2,633 castes covered under the OBC reservation. However, the Centre’s reservation policy from 1992 doesn’t take into account that there exists within the OBCs, a separate category of Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs), who are much more marginalized.

Its absence also results in inadequate budgetary allocations by governments to OBCs, a petition before the Supreme Court stated earlier this year. “Caste-wise census of the backward classes has [also] become imperative for implementing reservations in education, employment, Panchayati Raj elections, municipal elections,” it added.

In fact, the OBC community had sought a column for Socially and Educationally Backward Classes or the SEBC (the official nomenclature for OBC) in the census-enumeration form — which would record the exact caste of people in the SEBC category, if not the caste of every citizen. “Mind you, this ask is different from the demand for a full-fledged caste census that entails a complicated exercise of categorizing all castes, for which we do not yet have an official compendium,” The Print’s article noted. However, at present, this demand has been denied too.

“We have no idea how many OBC communities actually exist in India, leave alone their numbers. There are so many smaller communities, migrant groups which don’t make it to the census,” Anjali Salve Vitankar, a lawyer and anti-caste activist, told The Wire last year.

“[I]f you (government) don’t count us, how will you ever make fair welfare schemes for us (the OBCs),” she added.

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

India’s Rich Outlive the Poor by 7.5 Years Due to Health Inequalities: Oxfam Report