Helping a Teen Who Self‑Harms Can Be a Long, and Common, Journey

“As a parent, it’s really hard to cope with a child with self-harming behavior…. It’s natural to feel angry, frightened or guilty.”

The 16-year-old was feeling very overwhelmed. Her parents were mostly at work, she wasn’t doing well in her exams, her grandmother had passed away and her best friend had stopped talking to her after they’d had a fight.

In a teenager’s world, these problems could mean the end of the world. “I didn’t know what to do or who to speak to. Once I tried speaking about it with my older brother, but for him these were such trivial matters that he made me feel bad,” says the girl, whose name has been withheld to protect the identity of a minor.

Somewhere, she says, she had read that cutting one’s arm with a blade would ease stress. “I went to the bathroom and cut my left arm with my nails so hard that I did see blood, but it didn’t bother me. I wanted to continue and cut it more,” she says. “For some reason, it was making me feel good. My feelings of hopelessness were getting subsided, and I didn’t even realize, but self-harm had become a ritual.”

Why do teens cut themselves?

She is not the only teenager who self-harms. Psychologist Dr Manish Shah who specializes in teen behavior problems says, “When teens feel sad, distressed, anxious or confused, the emotions might be so extreme that they resort to acts of self-injury.” Besides cutting, he says, scratching, hitting, biting, picking skin, pulling out hair are also some methods teens might resort to when experiencing stress and anxiety, or to manage intensely bad feelings.

“The frequency could range from self-harming almost regularly, to less regularly, when they need an immediate release for built-up tension,” Dr Shah adds.

Self-harm may not typically be a suicide attempt, but it is a sign of extreme emotional distress, and in such distress, teens may consider suicide as well. In 2016, self-harm was the leading cause of deaths in India; a global study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) reported at the time that self-harm was responsible for close to 60,000 deaths annually in the age group of 15 to 24 years. It also indicated that self-harm had increased in the past two decades, signalling a rise in stress, mental health struggles, and changing behavioral patterns among teens. In 1990, self-harm caused close to half the number of deaths — 37,630, to be precise.

Read also: Healing The Scars Of Self‑Harm

While self-injury may be linked to a variety of mental health disorders, such as depression, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder, for most teens, “self-injury is an unhealthy way to cope with emotional pain, intense anger and frustration,” explains Dr Sujata Amlapurkar, a psychologist at Our Children Care Center in Mumbai.

“It may provide a sense of calm and a release of tension, but it’s important to remember that it’s usually followed by guilt and shame and the return of painful emotions. And with self-injury comes the possibility of more serious and even fatal self-aggressive actions,” Dr Amlapurkar warns. “Self-injury is an unhealthy and dangerous act and can leave scars, both physically and emotionally.”

For the 16-year-old who shared her story, it’s been a difficult journey. After cutting herself for two years, she sought help. “I managed to hide the scars from my parents but I knew it was time to confront them — looking at them had started making me sick,” she says. She added that her parents’ support and understanding encouraged her to visit a therapist. “It’s been a few months of counselling sessions, using my time more constructively and trying to face anxiety positively and I already feel better. I’ve not had the urge to cut myself,” she adds. Instead, the thoughts she often gets are of guilt and regret. “I cut myself for two years, I could’ve just asked for help instead and saved my time,” she says.

Helping teens who cut

“As a parent, it’s really hard to cope with a child with self-harming behavior…. It’s natural to feel angry, frightened or guilty,” Dr Shah says. “It may also be difficult to take it seriously or know what to do for the best. Try to keep calm and caring, even if you feel cross or frightened; this will help your child know you can manage their distress and they can come to you for help and support.”

If parents observe some of this behavior, and are generally worried, they should invite teens to talk about their worries, “…and take them seriously,” adds Amlapurkar. “Show them you care by listening, offer sympathy and understanding, and help them to solve any problems.”

Emotions like irritability, anger and sadness, often accompany other signs of self-harm, which might include changes in sleeping and eating patterns; losing interest in activities they enjoy; avoiding activities, such as swimming, that might expose their bare legs, arms or torso (and their cuts or scars); withdrawing from friends; skipping school; a drop in academic performance; hiding or washing their clothes separately (to hide blood stains); and/or wearing clothes that cover their arms and legs even if it’s hot or the clothes aren’t their style (to hide cuts or scars).

Article continues below

If a young person has injured themselves, Dr Shah says, the first step is to help them practically by checking to see if injuries (cuts or burns for example) need hospital treatment and, if not, by providing them with clean dressings to cover their wounds.

But a child who self-harms needs emotional help as well. Sujata Sharma, founder of SUPPORT, an NGO that supports, among other things, teenagers who self-harm, says that while most young people want their family’s help, professional help is also essential, if for no other reason than a professional can enable parents to better support their child at home.

Depending on a child’s needs, treatment might include psychological therapy or counselling, and parent or family therapy.

“Counselling can help teenagers understand why they’re self-harming, what triggers the self-harming and how to stop. It might include helping teenagers to understand and manage strong emotions, and learn more effective ways of managing and expressing strong thoughts and feelings,” she says.

She adds, “Your child might need to try a few times, or try a few different therapies, before she can give up self-harm. Different therapies work for different people. You can support your child in trying different approaches until she finds something that works for her.”

And for parents, she advises, while a child is working with a health professional, they can also let their child know that it’s normal to reach out to friends or family for help when something upsetting happens.

Anubhuti Matta is an associate editor with The Swaddle. When not at work, she's busy pursuing kathak, reading books on and by women in the Middle East or making dresses out of Indian prints.

Related

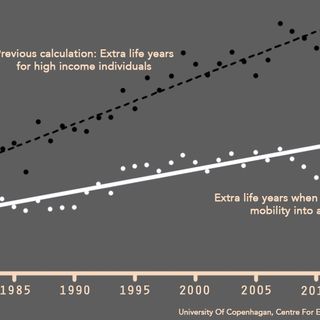

Rich and Poor Have Similar Life Expectancies, Says Comprehensive Data Study