How Novels Have Shaped Women’s Understanding of Sex in the Absence of Sex Education

Despite its pitfalls, literature has helped many women recognize, and come to terms with, their sexual desires.

“My first exposure to women masturbating and taking control was through Paulo Coelho’s Eleven Minutes… For quite some time I had thought it was only men who masturbated. The idea of a woman pleasuring herself was alien to me. But the book actually encouraged me to try it out,” Khushi, 18, says.

The glaring lack of sex education in India is hardly a secret — unlike the incredibly taboo topic of sex in the living rooms of Indian families. So, like Khushi, I, too, learned about female masturbation from Eleven Minutes. Not only that, until I read the book, I didn’t even know women could orgasm. I was eighteen at the time — eight years since I had reached puberty.

But unlike Khushi and me, young, impressionable people from around the world often resort to porn as their first and primary tool to learn about sex. Unfortunately, however, porn often depicts non-consensual sex and is primarily geared towards male pleasure, leading to sexist attitudes around sexual relationships.

But for many women my age, growing up in a non-Internet era made porn difficult to access and, coupled with the idea that “good girls don’t watch porn,” steered us toward literature instead to satiate our curiosity. And so, literature – be it in the form of books by Sidney Sheldon, Julia Quinn, Stephenie Meyer, or the wildly popular but staunchly criticized works of Chetan Bhagat, or even the Archie-comics, as 26-year-old Samiha points out, became our source of sex education. Moreover, unlike porn or erotica, “I could get them in a bookshop, accompanied by a parent, and there would be no questions asked and no fingers raised,” Anahita, 25, recalls. “They looked harmless. Basically, no one kind of knew that they could contain salacious passages. So, somehow, it didn’t even feel ‘wrong’ because I wasn’t sneaking out or breaking any rules,” she adds.

“[I]f sex includes some of the most exhilarating, passionate, and devastating experiences in a person’s life, shouldn’t sex education address exhilaration, passion, and devastation?” Jen Gilbert, a professor at York University in Canada, who focuses on sexuality education, youth studies, and LGBTQ+ issues in education, wrote in a 2004 paper. “[Yet] sex education does not stray far from the sterile presentation of facts or moralistic admonitions to say no. Where, then, might sexuality find an education in the affective? Where might youth, and adults for that matter, speculate on the complicated relations between sexuality in all its guises and the passions?” Gilbert goes on to ask.

Her answer: novels. “[A]n engagement with novels might offer not only a curriculum to engage the concerns of youth, but also a method for reading youth cultures [and] address[ing] the complications of love and identity,” she wrote.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the Morning‑After Pill Became the Most‑Used Birth Control for Young Indian Women

Literature, in fact, made Anahita feel more comfortable about the idea of a non-hairless female body – especially with the idea of women not “needing to shave” their pubic hair. This was a result of her reading a book that referred to a woman’s pubic hair as the “thick dark curls of womanhood.” It made her think, “Oh, so you can just leave it there!” She says she was exposed to it in her adolescence, at a point when she was beginning to explore the norms around the wat our bodies present. Unlike contemporary, mainstream pop culture at the time – like Sex And The City, for instance, which put forth quite the opposite notion– the novel opened Anahita’s mind to the idea that pubic hair isn’t “shameful.”

Books have helped many women recognize and come to terms with their desire too. Dhvani, 29, for instance, credits works of fiction for giving her insights into how a sexual relationship plays out. She says it felt like “the safest, if not the most accurate, source… [The books] gave me privacy [to absorb its contents], and time to think about how I felt about the things I read.”

She mentions that despite being a student of biology and knowing the basics, “the books helped when I had my first sexual experience… They had painted a very pretty, happy, and satisfying picture of sex, so I was a little disappointed with how my ‘first time’ went. But the books also gave me the courage to keep trying to have better experiences, and to initiate conversations [about sex] with my friends, and with my partner,” she explains. Basically, literature enabled her to work towards a richer, more fulfilling sex life.

Books also exposed people to parts of sexual intimacy – like foreplay for Anahita – that can serve to make their first-hand sexual experiences better for years to come. Anahita also recalls that in a lot of the books she read, “women were at the receiving, or learning end – like the men would often be more experienced, and taking her through it.” This also taught her about how “different things feel like and stuff.” It, perhaps, reflects the male gaze that leans towards portraying “respectable” female characters as sexually innocent creatures — perhaps, virgins even. But, ironically, it served the purpose of enlighening their readers — including women, of course — about sex.

Besides providing insights into how intercourse plays out, literature can, through stories, also lend young readers context about the socio-political discourse around sex – be it through explorations of consent, commitment, safety, or, simply, emotions.

However, while literature certainly appears to be a better, safer source of knowledge about sexual relationships, just like porn, it too often isn’t created with the objective to educate, and so, can promote toxic ideas. For one, besides being heteronormative, many mainstream works of literature tend to conflate sex with romance.

Related on The Swaddle:

According to 3.5 Million Books, Women Are Beautiful and Men Are Rational

“The literature I read almost always combined sexual relationships with romantic ones — otherwise the character was deemed a ‘slut’ or a ‘whore.’ As a result, in my own life I ended up romanticizing sexual relationships even though I didn’t actually have any romantic feelings for many of those people,” Rhea, 21, states. “Ultimately, the literature I was exposed to, more or less contributed to me having very unstable relationships with many sexual and romantic partners… I regret having picked up and implemented toxic ideas. But I thought they were normal and that’s what sexual relationships and romance were supposed to be like,” she added.

A., 28, too, speaks of absorbing toxic ideas through literature — primarily, Mills and Boons and Harlequin romances that she stumbled upon in her mother’s cupboard. “They were pushed very heavily on the gender roles of your ‘alpha male’ and your ‘damsel in distress’… The sex, in some cases, was even a bit ‘rape-y,’ in hindsight… And it kind of drilled into me that sex is just that — a penis going in a vagina,” she says.

Unlike Anahita, for some women, relying on literature for knowledge about sex, also led to them feeling less confident about their bodies. “[Books] made me doubt my desirability owing to stretch marks, and not having ‘smooth’ and ‘white’ skin,” Khushi notes.

However, this is not to say that learning about sexual relationships through literature is a terrible thing. It is in the absence of proper sex education that notions they propagate might be harmful – just like with porn. “It took me an incredible amount of time to come to terms with that fact that I can just enjoy sex without having to be in a relationship… If I had comprehensive sex education to teach me instead, I would’ve taken the literature with a pinch of salt and used it only as something that would enhance my imagination and if anything give me more ideas for the bedroom,” Rhea adds.

Thus, despite its pitfalls, literature has helped many women recognize and come to terms with their desire. In a better — if not “ideal” — world, literature can potentially even serve as a helpful tool to make sex education more robust.

As S.A., 25, says, “It was reading that helped me understand my kinks better… But I do wish I had access to sex education and wellness books too sooner, because these peeks into reality helped me understand the fiction I was reading much better.”

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

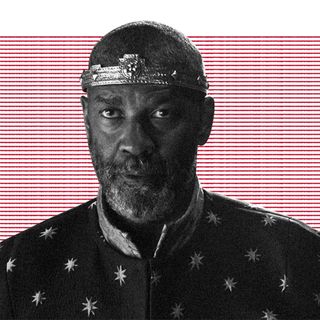

In ‘The Tragedy of Macbeth,’ Denzel Washington Carries a Familiar Legacy in a New Direction