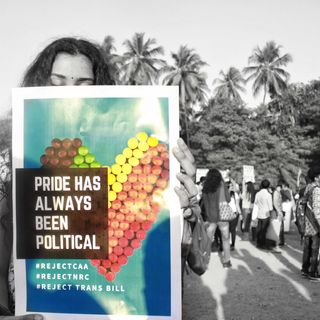

For Women at Protests, Challenging NRC‑CAA Starts With Defying Sexism at Home

Women are out and willing to fight because they want to take part in decision-making and challenge the men.

I.K., 18, had told her parents she had extra classes every evening to help her prepare for her class 12 board exams. The truth was, she was at the anti-NRC-CAA protests taking place at Sabzibagh, in Patna, Bihar. “If I didn’t lie, I would’ve never been allowed to get out alone after sunset,” she says. “The idea of attending protests goes against my parents’ idea of what decent, honorable girls do. They barely agreed to let me go study in a college of my choice.”

But a neighbor told her parents after spotting I.K. at a protest. Since then, they’ve threatened to marry her off. But that has not stopped her from protesting. “They think nobody will marry me now because I lack manners and being out on the streets is not what girls from good homes do,” she says.

I.K. is one among thousands of women across the country, in cities big and small, from Gaya and Patna in Bihar to Kolkata, to brave one of the country’s coldest winters to protest day and night against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC). They see these as ominous, particularly for the country’s Muslims because unlike people from any other religion, they could be stripped of their citizenship if they fail to provide documents to prove the same.

What’s visible is that these women protestors span across age-groups, religions, and class. But their invisible, yet notable, common thread is that a majority of them come from homes that adhere to strict gender norms. And for these women, getting out to protest, despite the resistance from their families, is a first. And a very big sign that they are as ready to take on sexism as they are to challenge discriminatory laws.

“In small towns like ours, our daughters-in-law don’t even go up to the terrace,” says Fatima Khan, a businesswoman and one of the organizers of the protest in Shantibagh, in Gaya, Bihar. “They don’t step out unless accompanied by men. Many who are sitting here are doing it against their family’s wishes only because they have realized it’s time that women also want to be heard and seen.”

“We gave the men enough chances. But they couldn’t do anything.”

For 33-year-old homemaker Asma Amir’s father-in-law, her going out at night is against the rules of the house. “He’s always known me as a meek, obedient, ‘good’ girl. But now, he thinks I’m a bad influence even for my children,” Amir says. “He told me, ‘which mother leaves her children all night to be on the streets?’ But he fails to understand that I am actually fighting for their future.”

In S.A.’s home in Patna, her in-laws have called her parents multiple times to complain that their daughter is a “rebel.” “My mother-in-law once told me that women who get out at night are those who are into ‘dirty work,’ and that I was being a disgrace to their family,” S.A. says. “But I continue to come here, fight for our existence and our future. If they ask me to leave, I will.”

Related on The Swaddle:

How Being at the Frontlines of Protest Is Taking a Toll on Women’s Health

“Here for our rights”

This nationwide women-led movement is a watershed moment in the history of independent India.

“They have forced us, housewives, to get out of the house,” says Afreen Shahbaz, a 33-year-old homemaker from Park Circus in Kolkata. “For us, our home was our only world. Now, we have to fight people in this very home to keep our larger home, i.e., the country, intact.”

With that purpose at the forefront of their protest, neither the cold nights, nor the three shootings by gunmen, nor several threats of forceful evictions have been able to deter the determination of these women.

“Ab paani sar ke upar se chala gaya tha (the water had crossed above our heads, enough is enough),” says Shahbaaz. “We gave the men enough chances.” She explains that the women protesting have felt all along that men were doing something to fight for their rights. “But they couldn’t do anything. They didn’t get the Triple Talaq law repealed or fight for the rights of our Kashmiri brothers and sisters when Article 370 was implemented. They’ve even failed to provide us enough safety to walk on the streets without the threat of being raped looming over our heads,” Shahbaaz says.

To the outside world, these women’s dominance of recent protests may come across as a strategy in which men push women to the frontlines because women are less likely to be lathi-charged by police. In some places, this may be true — but women have taken advantage of any spotlight orchestrated by men to vent their built-up frustration at the sexism behind such actions and the patriarchal restrictions they face every day.

This has not only created a moment of shock and awe, but also created an understanding that the movement, like other movements with women and children in it, is progressive and likely to succeed against any injustice.

Related on The Swaddle:

All the Arguments You Need: to Convince People Protests Work

“When the fight is long and hard…you need women”

“Issues that affect habitat, livelihood or right to shelter can mobilize women faster,” Medha Patkar, activist and lead campaigner of the Save Narmada Movement, told TIME.

“India sees these women as shields, but in fact, they are the swords.”

If implemented, the NRC-CAA will affect the poor and other marginalized communities most, as they scramble to obtain documentation to prove they are Indian to avoid being put in detention centers. And history is proof that it is women across socioeconomic strata who do end up suffering the most.

“We women are always at the receiving end with all kinds of restrictions imposed on us in the name of honor and the society’s ideas of femininity,” says Khan. “So yes, this is a fight for the government to take back the draconian law, but it is also a huge opportunity for us to tell the men that we don’t want to give up on all the little freedoms we’ve managed to fight for all along.”

For some, these freedoms have meant fighting to access even basic, formal education. Anjum Khan, an 18-year-old student and a regular at the protests in Shantibagh, says, “I come from a conservative family where we get married as soon as we turn 18. It was my mother who fought with my father to let me go and study in Delhi because she knows that’s my only weapon to fight against all the injustice.”

“So today, her fight is not just against the CAA, it is also to preserve our right for education,” she adds.

A professor and one of the organizers of the Park Circus protest, Nousheen Baba Khan, 34, explains, “Women are out because, in issues that affect them directly and their families, they want to be the ones making a decision this time. They’ve had enough with men deciding for them.” She adds that many of these women leading the protests are the first ones in their families to have formal education. “And anything that threatens this right will keep them motivated to stay mobilized,” she adds.

When the fight is long and hard, you need women, Patkar added. “The specialty of women-led movements is that they can be sustained longer. Women don’t give up,” Patkar told TIME. “India sees these women as shields, but in fact, they are the swords.”

The women agree. “It was our kids getting beaten up, how could we have not reacted,” says Nusrat Hassan, a 34-year-old school teacher from Gaya. “They were out to protect the Constitution and their Bharat Mata (Mother India). We showed them together we can all be Bharat Matas not only to protect our children but also the country.”

Today, it has been more than 50 days since the first women-led protest in Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh began, setting the example for women in other places to follow suit. At protests across the country, the women say they continue to face resistance — but they will continue to fight.

“In difficult times, a woman’s first response is to stay and fight. That’s the beauty of women-led movements. They never die,” Patkar told TIME.

Anubhuti Matta is an associate editor with The Swaddle. When not at work, she's busy pursuing kathak, reading books on and by women in the Middle East or making dresses out of Indian prints.

Related

Mothers‑in‑Law Restrict Women’s Reproductive Agency by Isolating Them: Study