Are We Becoming Less Empathetic by Choice?

A new study suggests people are avoiding empathy because it takes too much mental effort.

Empathy is a trait that humans evolved to keep our species alive. While not a uniquely human characteristic (primates, dogs and rats all display rudimentary empathy), we have honed empathy into building relationships and communities to a degree and complexity no other species can.

And yet, in a modern world full of overexposure to people, problems and demands on our minds and time, a new study suggests we’re pulling back from one of our most foundational survival skills — by choice.

“We saw a strong preference to avoid empathy even when someone else was expressing joy,” C. Daryl Cameron, PhD, said in a statement.

Cameron is the lead researcher among a team that examined when and why people avoid understanding and engaging with the emotions of another person. In a series of experiments designed to test the cognitive cost of empathy, and involving more than 1,200 people, participants selected images that required empathetic engagement only 35% of the time. In surveys after the tests, most reported feeling more mentally challenged, and less good at, engaging with empathy, than they did at the other option: simply describing the images.

“There is a common assumption that people stifle feelings of empathy because they could be depressing or costly, such as making donations to charity,” Cameron said in the statement. “But we found that people primarily just don’t want to make the mental effort to feel empathy toward others, even when it involves feeling positive emotions.”

Empathy takes brain power. Social scientists differentiate between three types of empathy: emotional, which requires someone to feel the same feeling as another, feel distress that the person is feeling that feeling, and generate a concerned response; cognitive, which is basically the emotional intelligence to perceive and identify others’ emotions accurately (also called Theory of Mind); and somatic, which is a physical response that mirrors another’s (think: sympathetic puking).

Of these, emotional empathy is the one Cameron’s study explored. And while people may not be stifling empathy out of concern about money, as Cameron says, mental effort is a cost — possibly the most valuable commodity we have in our current, constantly-plugged-in, always-on-demand world.

“My grandmother has a phrase she always told me — I don’t know if she could tell I was an overly empathetic person, or it was just good life advice,” my colleague Rajvi told me when I pitched this piece. “‘When you offer a finger, people will often grab the whole arm,’ she said. ‘Don’t let them grab it.’

It sounds a lot like advice my own mother — probably the most wonderfully empathetic person I know — had given me when I was young: Don’t overcommit your time, or your self. “Learn to say no,” she had said. (Spoiler: I haven’t yet.)

As I started to poke around into the mental cost of empathy, the anecdotes flew thick and fast, mostly from women, about how they have learned, or feel they need to learn, to dial back their empathy.

“My tendency to show empathy to everybody, even strangers, has led me deep into toxic relationships, where I knew I was being taken advantage of, but I didn’t have the heart to create any distance. I was ‘offering my whole arm,’ often without even being prompted. Many times, that was affecting my self-esteem, mental health, and daily life immensely,” Rajvi said.

“I was so naive, I would often think that if I were extra nice to people, they’d like me more,” said my colleague Sanskrita in the same meeting. “But slowly, I realized people often started taking my ‘niceness’ for granted, took advantage of me. I know I almost make myself sound like a victim, but I kind of feel it’s true. Over the years, I have tried to work hard towards not showing empathy to people, which is why I am deeply intrigued by people who are indifferent. Even if they’re pretending to be indifferent, I admire the fact that they’re pulling it off.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Women’s Mental Load Linked to Distress, Dissatisfaction, Study Finds

Despite popular belief, there’s no evidence that women are more biologically tuned to empathy (in fact, there is evidence instead that women’s tendency to it is because of gendered expectations). But there is an accepted theory that women unequally shoulder the burden of ’emotional labor’ — aka the mental effort required to engage in empathy — a term coined by psychologist Arlie Russell Hochschild as far back as 1979, and identified as “feminism’s next frontier” nearly three decades later.

The thing is, the well of cognition from which empathy pulls can dry up — it’s known as compassion fatigue, and while there’s nothing in Cameron’s study to conclude this avoidance of empathy is due to compassion fatigue (or is limited to women; the researchers studied both genders), other research has shown empathy lessens when cognitive resources are depleted.

“Now, I treat the act of offering empathy through the lens of self-care. Is showing empathy to this person going to affect my state of mind? Is being there for someone going to mean I’ll give myself less consideration, less time? If the answer to these isn’t a resounding no, then I decline somebody’s ask for help,” Rajvi told me. “If I’m not in the most sound of minds, then I won’t be able to help them to the best of my abilities anyway.”

The decline of empathy in society has been observed for a while. A study of 14,000 American college students in 2011 found they exhibited empathy approximately 40% less than their peers in the 1980s. The fact that it might be a choice, made in the name of survival, makes it all the more disturbing.

But Cameron offers hope for reclaiming our most basic survival skill. In the same statement, he points to the key fact that people were often avoiding empathy because they didn’t feel they were very good at it. So, let’s figure out how make them good at empathy, he says.

One way to do that might be in learning to differentiate between empathetic distress and empathetic concern — while both are technically steps within the academic definition of emotional empathy, it’s possible to get more hung up within one than the other. Studies of doctors and others in caregiving professions have led some experts to posit that empathetic distress leads to compassion fatigue, burnout and poor health, while empathetic concern leads to fulfillment, help and good health.

But empathy has two sides — the person who asks for it, and the person who extends it.

“I actually think we need to change the way we ask for empathy, and what we consider enough from whom we’re asking,” Rajvi told me. “Not to require the person giving empathy to do the work to figure out what is healthiest, but to check ourselves when we require empathy of someone — are we asking them to be our therapist? Or do they simply need to give 20 minutes and listen?”

While accidents, loss, violence, poor health and twists of ill-fate beyond human control will always call for compassion, perhaps what millennials (and Gen Z-ers) are choosing to withdraw from is empathy for what they perceive to be self-made problems. Raised to be the self-help and self-care generation, millennials have a greater use of mental health therapy and a greater commitment to self-improvement than previous generations — which perhaps translates to a refusal to empathize with those we perceive as not putting in the self-work. Therefore the question isn’t whether society is becoming less empathetic by choice, but whether people are falling through the cracks without it. Millennials have been widely credited as the generation working to end the kind of stigma that prevents people from accessing professional mental health services; perhaps human empathy has just taken a different form, evolving once more in a way that enables a healthier survival for everyone.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

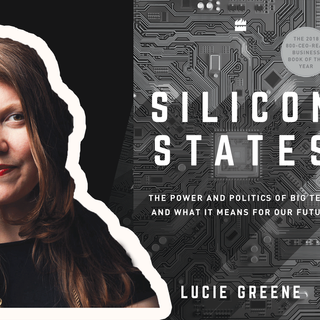

‘Silicon States’ Author Lucie Greene on the Gendered Dangers of Big Tech