Scientists Warn Mini‑Brains Used in Lab Research May Be Able to Feel

A group of neuroscientists says it may not be ethical to keep using these mini-organs for research.

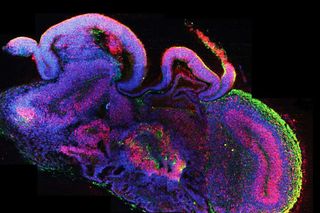

Some neuroscientists are warning the scientific research community is “perilously close” to crossing an ethical line in experiments on neural organoids, that is, small cultures of brain tissue that exhibit basic neural connections, generated for research purposes. In other words: man-made mini-brains on which we experiment.

These scientists, at the Society for Neuroscience conference in Chicago last week, suggested these neural organoids may be somewhat sentient or able to feel pain. They’re calling for a halt on all brain organoid research and funding of such research until the scientific community can establish checks and balances to the unique situation.

“We’re already seeing activity in organoids that is reminiscent of biological activity in developing animals,” Elan Ohayon, one of the concerned scientists and the director of the Green Neuroscience Laboratory in San Diego, California, told The Guardian.

Organoids grow from cultured tissue samples, embryonic stem cells, or cells that have been reverse-engineered into stem cells (known as induced pluripotent stem cells). Developed in the 2010s, they revolutionized experimental capacity by giving scientists an eye into how the organ these clumps of tissue resemble actually functions. Organoids have been especially helpful in studying and experimenting on organs too integral to life to allow for much experimentation while within the human body, particularly the brain, the stomach and intestines, the lungs, the kidneys, and many glands. So far, brain organoids have helped shed light on autism, schizophrenia, and the birth defects associated with the Zika virus, among other research purposes, The Guardian reports.

Related on The Swaddle:

Japan Approves Research to Grow, Harvest Human Organs from Animal Embryos

But recent research has suggested brain organoids, at least, may mimic actual organ function a little too closely. The Guardian report cites two particular studies, one by Harvard Researchers that found brain organoids develop a diversity of neural tissue, including cells of the cerebral cortex and cells found in the retina of the eye, and a neural network to coordinate communication between different parts; the retinal cells responded to light in a manner similar to retinal neurons found in full-fledged human brain networks. Another study found that when human brain organoids are transplanted into mouse brains, the human brain organoids connect to the mouse’s blood supply and grow new connections.

This last experiment harks to a related debate raging within the scientific community lately, one involving chimeras. Chimeras are animals with hybrid animal and human tissue, like the above mice; in August, The Swaddle reported, Japan set off a scientific firestorm by approving such human-animal crossover embryo experimentation up to the threshold of an animal comprising 30% human tissue, at which point the chimera embryos would have to be terminated.

Ohayon is not the first to call for more carefully considered, ethical guidelines for organoid research. In 2018, The Guardian reports, a group of scientists, lawyers, ethicists, and philosophers advocated for an ethical debate around organoid research. While they acknowledged that the organoids currently used in labs are not advanced enough to cause immediate concern, they wanted to get ahead of the issue. But to Ohayon, the issue is already at hand.

Scientific ethics is always a gray area, especially when new, critical discoveries have been made and their path of discovery holds the promise for more insight. Ohayon doesn’t think these mini-brains are yet capable of human thought and emotions, but “the potential to perceive or to react to things, that seems to me likely,” he told The Guardian.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Areas Affected by Heatwaves to Increase 50‑80% by 2050 Due to Greenhouse Emissions