Life at the bottom rungs of the social ladder inevitably comes with negative health consequences — this is known. But new research in monkeys suggests the chronic stress of life at the bottom may have long-term effects at a cellular level, that even later upward mobility can’t undo.

The findings of the study extend the theory of biological embedding in humans — the idea that experiences in the first few years of life are formative and leave long-term effects on our biology and development. Apart from shedding light on how stressful social experiences can get ‘under the skin’ and influence long-term health, the latest study suggests biological embedding processes are at work even in adulthood.

“Events that occurred in adulthood can also have a long-term impact on the function of your cells and biology of your system,” Luis Barreiro, Ph.D., the study’s co-author and a University of Chicago geneticist, said to UChicago Medicine. “Somehow, the cells in our body remember something about our social experiences, even though they may have happened months or up to a year ago.” The study was conducted by Barreiro and Duke University evolutionary anthropologist Jenny Tung, Ph.D. and its findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In humans, there is a direct correlation between socioeconomic factors such as income, place of residence and education, and chronic stress. But studying the relationship between socioeconomic factors and health is tricky due to variation in factors such as access to health care and diet across any given population. To overcome this, the researchers studied female rhesus macaques, kept under observation, so they could keep these variables constant — and then manipulate social status to see its changing effect on health.

Rhesus macaques live in defined hierarchies that directly shape everyday life and are enforced through both non-aggressive and aggressive methods. Macaques compete with each other until a pecking order is formed. Those higher up the social ladder get first dibs on food, space and grooming, and even bullying rights. Those who are lower on the ladder wait their turn and get pushed around silently.

“In this system, social rank is a proxy for chronic stress in humans,” Barreiro told UChicago Medicine. “If you’re a low-ranking monkey, you’ll receive more harassment from others.”

Related on The Swaddle:

How Money Affects the Psychology of the Extremely Rich

At the beginning of the experiment, the researchers introduced unrelated macaques who didn’t know each other, one by one, and put them in groups of five. One year later, the researchers shuffled all the groups and re-introduced the macaques to each other in a different order.

In both cases, macaques introduced to groups earlier earned a higher status. But after the switch, some macaques who were high-status in their previous group fell down the ladder, while some low-status macaques became the highest-ranking in their new groups.

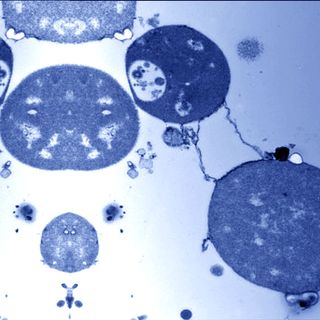

Blood samples of the macaques’ taken after the switch were exposed to agents that mimic bacterial or viral infections. In a 2016 study, Barreiro Tung found a female macaque’s rank affected how thousands of genes turned on and off, especially genes involved in fighting infections. In low-ranking females, some of these genes are stuck in overdrive, causing inflammation.

The findings of the study show that a macaque’s past social rank continued to influence its genes even after the switch; specifically, the researchers found 3,735 genes whose activity was still influenced by a macaque’s former rung in the social ladder, irrespective of their current status.

“We all have baggage,” Tung said in a press release. “Our results suggest that your body remembers having low social status in the past. And it holds onto that memory much more than it would if things had been really great.”