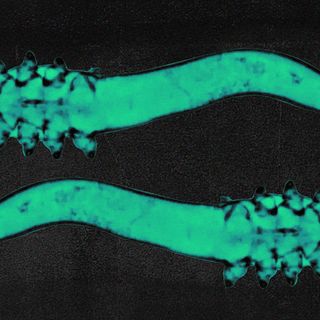

Back in 2009, in the distant reaches of a mangrove forest in the Caribbean, a marine biologist noticed something strange while poking around in the water from a swamp. Thin hair-like strands floated around, visible to the naked eye.

“In the beginning, I thought it was just something curious, some white filaments that needed to be attached to something in the sediment like a leaf,” said Olivier Gros, the biologist in question. But the truth ended up being far stranger than fiction — the tiny strands turned out to be single-celled bacteria. This discovery changes our understanding of the hitherto solely microscopic species, forever.

Since then, scientists have examined the thread-like organism closely to confirm, finally, that it is indeed a single-celled bacterium — the largest to have ever been found.

The findings were published today in Science, and confirm that the creature is indeed a gigantic single-celled bacterium with more complex internal mechanisms powering it than any other known bacteria. This would not only make it the largest known bacterium in the world, but it also subverts the rules of prokaryotes — a family of organisms that lack internal membrane-bound organelles (like a nucleus). The giant bacteria, named T. magnifica, does however store DNA and ribosomes inside tiny membraned organelles called “pepins.”

The defining feature of T. magnifica is its size spectacularly dwarfing that of any other kind of bacteria, which are about 2 micrometers long. T. magnifica‘s cell length is over 9,000 micrometers, and it’s around 5,000 times larger than most bacteria. “To put it into context, it would be like a human encountering another human as tall as Mount Everest,” said marine biologist Jean-Marie Volland, lead author of the study.

Related on The Swaddle:

In a First, Scientists Discover 3 Sexes in an Algae Species That Can Mate With Each Other

“These cells grow orders of magnitude over theoretical limits for bacterial cell size… and challenge traditional concepts of bacterial cells,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

Its size is not the only distinguishing factor. Where other bacteria grow in volume to split and reproduce, T. magnifica simply detaches a part of itself. It also has a much larger genome, and can also distribute the protein that produces ATP (the energy source of cells) across wider ranges, influencing its size. The pepins, moreover, host around 700,000 copies of the bacteria’s genome.

Researchers are still not sure why they evolved to become this big. “By leaving the microscopic world these bacteria have definitely changed the way they interact with their environment,” Volland told The Guardian. On the one hand, they may have become hundreds of times bigger than their predators, thereby evading them. On the other, they can no longer move around and colonize spaces as easily or as quickly.

These findings prompt researchers to look for even larger bacteria that may be “hiding in plain sight” according to the study. “There’s probably an upper limit on cell size at some point, but I don’t think it will be peculiar to bacteria or archaea or eukaryotes,” Petra Levin, from Washington University, told Nature.

“We really should not underestimate evolution, because we can’t guess where it’s going to go… I would not have guessed this thing exists, but now that I see it, I can see the logic in the evolution to this point,” Levin added.

For now, the discovery prompts amazement at the sheer range, scale, and adaptability of the living world. Hence the name, perhaps — referencing “magnifique” in French.