Lymphogranuloma Venereum: Chlamidya, but Worse

You can pass the infection on to sexual partners at any stage even if you don’t show the symptoms.

Lymphogranuloma venereum LVG) is one of the more invasive manifestations of the common sexually transmitted infection, chlamydia.

LGV is a long-term (chronic) sexually transmitted bacterial infection of the lymphatic system, which is a network of tissues and organs that transports lymph, a fluid containing infection-fighting white blood cells, throughout the body.

What causes LGV?

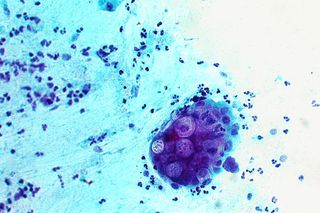

LVG is caused by specific strains of the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis (strains L1, L2, L2b, L3). These strains differ from those that cause other manifestations of chlamydia — such as trachoma (a bacterial infection that affects the eyes) and chlamydial urethritis and cervicitis — because they can invade and reproduce within regional lymph nodes, and spread through the body.

Who is more at risk for LGV?

Like all sexually transmitted infections (STIs), anyone who has vaginal, anal and/or oral sex without using a condom can acquire LGV. However, it is diagnosed more often in men than women, especially in HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM).

LGV occurs sporadically in the U.S., Europe, and Australia but is regularly diagnosed in parts of Africa, India, Southeast Asia, South and Central America, and the Caribbean.

How is LGV transmitted?

LGV is almost exclusively sexually transmitted — passed from person to person through direct contact with skin lesions or ulcers.

The bacteria enter the body during penetration (vaginal, oral, or anal) through moist tissue — most commonly, the rectum or vagina, but infections can also begin in the penis or the mouth.

Unprotected anal intercourse is the activity with the highest risk of LGV transmission.

What are the symptoms of LGV?

It can take three to 30 days between exposure to an infection and first appearance of symptoms such as fever, muscular pain and swollen lymph nodes in the head and neck region, armpits, and groin. The infection spreads in three stages. The symptoms vary depending on which part of the body is infected, such as the genitals, anus, rectum, mouth, and lymph nodes.

Stage one begins after an incubation period of three days after exposure. A small, painless blister or sore appears at the site of entry of the infection — usually the genitals or the rectum, but also potentially around the anus, on the lip, or in the mouth.

The overlying skin on these lesions may break down (ulcerate), but heal so quickly, they may go unnoticed. They also can appear in groups, which may look like a herpes infection. Like other STIs that cause skin ulcers, LGV may facilitate transmission and acquisition of HIV.

Those who practice receptive anal sex may see other symptoms develop, such as the inflammation of the rectum lining (proctitis), rectal ulcers, bleeding, pain, and discharge. Other symptoms include fever, tiredness, rectal pain, discharge, bloody stools, constipation, and a feeling of needing to empty the bowels regularly. However, many people have no symptoms at this stage. This is particularly true for women, since the skin lesions may remain undetected in the urethra and vagina.

Related on The Swaddle:

Undiagnosed Sexually Transmitted Infections Can Make PMS Worse

Stage two begins after two to four weeks. In men, lymph glands in the groin, armpit or neck become inflamed, forming large, tender masses (buboes). These can cause the overlying skin to become inflamed, sometimes accompanied by a fever. Women may suffer from backache or pelvic pain. If the initial skin lesion is on the cervix or upper vagina, the lymph nodes around the rectum and pelvis may become enlarged. Multiple draining tracts — narrow passageways under the skin through soft tissues — may discharge pus or blood into the body.

By stage three, most people recover with appropriate treatment. Lesions heal, though tracts can persist or recur. If left untreated, the symptoms worsen, causing swelling of the lymph glands and genitals, genital ulcers, and rectal or vaginal damage, causing lasting injury to infected tissue and general health. Persistent inflammation because of the untreated infection obstructs the lymphatic vessels, which may lead to scarring, swelling, and deformity in the infected areas.

Most importantly, you can pass the infection on to sexual partners at any stage even if you don’t have the symptoms.

How is LGV diagnosed?

LGV can be complex to diagnose since the lesions caused by it resemble those caused by other STIs, such as syphilis, genital herpes, and chancroid; buboes in the lymph nodes may be mistaken for abscesses caused by other bacteria.

Tests for chlamydia — which involve checking a urine sample or taking swabs from affected areas, such as the rectum, urethra, vagina or throat — also detect LGV, so a negative chlamydia test means no LGV.

If you test positive for chlamydia and have LGV-type symptoms, you will need to take specialized tests to ascertain whether the infection is LGV rather than another type of chlamydia. These are antibody detection tests and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT).

It is common for LGV to be diagnosed at the same time as another STI or blood-borne infection, most commonly syphilis, gonorrhea or hepatitis C.

What is the treatment for LGV?

There is no vaccine against the bacteria. Most cases can be treated using a three-week course of the oral antibiotic doxycycline with erythromycin base, or azithromycin being substituted in the case of pregnant women.

Can LGV be prevented?

Well, yes, if you avoid all sexual contact or enter a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with someone who has been tested for LGV (and other STIs) previously and given a clean bill of health.

For all other scenarios, the risk of LGV infection can be reduced by using male latex condoms consistently and correctly during sex. Washing up after sex is always a good idea. Using condoms with shared sex toys and cleaning them with hot soapy water between uses can also reduce the risk of contracting LGV. Latex gloves should be used for fisting; just like condoms, a new glove should be used with each partner in case there is more than one.

If you have or suspect you have LGV (or any other STI), don’t have sex until follow-up tests confirm you are no longer infected. Having had LGV and completing its treatment does not prevent re-infection. To avoid this, make sure each of your sexual partners has also been tested and treated.

If you discover you have had sex with someone who has LGV (or any other STI), don’t have sex again until you have had a checkup. In general, it is good practice to have regular checkups for STIs.

This is part of our series on sexually transmitted infections.

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Related

Unpacking Bipolar Disorder and Its Various Classifications