With Expiring Copyrights, Marginalized Communities Can Rewrite Fiction History

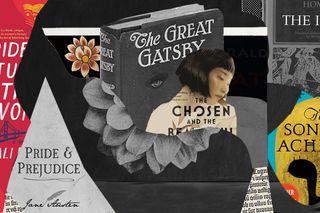

Imagine ‘The Great Gatsby’ with a queer, Asian, woman protagonist.

On the last day of December, as the entire world watches the clock slowly tick to a new year, art and literature enthusiasts have something more to look forward to. The first of January marks the day hundreds of books begin a new life in the public domain — essentially allowing anyone under the sun to release them freely, create their own versions, or mash them up with other art.

All works of art, when created, are copyrighted to enable authors to benefit from their creative work. But these rights last for a limited period (roughly, the length of a lifetime). When they expire, the works go into the public domain, where they can reach more people, more easily.

While the end of copyright for celebrated works allows new authors and adapters to legally build upon classics without paying an enormous licensing fee, what it more importantly brings is cultural leeway: The public domain allows people to reimagine a story — with, say, a more inclusive cast, with a categorically different set of characters and values, set in a different time period, etc. And while this expanded scope for creation holds value for all artists, it has profound consequences for creators from marginalized communities, who now have the opportunity to reclaim some of the power these books hold over their communities and introduce audiences to previously unpublished experiences through an already familiar story.

The world of literature — and especially acclaimed English literature — has historically swum in the deep waters of privilege. To be an author a century or two ago meant to belong to any (and mostly all) of the following boxes: white, rich, heterosexual, and male; and so did being a reader. Regardless of the presence of intellectual stimulation and emotional stir — or the lack thereof — the truth was that esteemed, mainstream art originated from a fusion of cultural and economic dominance, colonization, and white male privilege. And so, art developed as a hobby meant for the entitled, largely by the entitled; which meant that in this gilded world, anyone who did not check these boxes did not have a voice.

Related on The Swaddle:

According to 3.5 Million Books, Women Are Beautiful and Men Are Rational

For marginalized communities, recreating and reimagining these revered classics is about reparation — taking back the power from oppressors and colonizers by adapting their stories to lesser-represented lives. This not only gives the stories a fresh perspective but also helps retrospectively answer the big question — what about the rest? It works to fill gaps in historical storytelling. Through retellings, the stories untold so far but just as important as the story of the alpha-male victor — stories of the slaves, of the women, of the vanquished, and so on — are finally given space.

Homer’s Iliad and The Odyssey, for example,are classics that have long been in the public domain. They narrate the tale of the great Trojan War and its aftermath and have been major inspirations of retellings for decades: Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles imagines a queer relationship between Achilles and Patroclus; A Thousand Ships, by Natalie Hynes, narrates the story of the women left half-fleshed out in the original epic; The Penelopiad, by Margaret Atwood, retells the epic from Penelope’s point of view. Closer to home, Chitra Banerjee Devakurni’s Palace of Illusions tells the epic Mahabharat from the life and perspective of Draupadi.

By creating new stories from universes already familiar to the world, by adapting these well-known stories to contexts that are barely represented, marginalized authors can individualize celebrated works to less mainstream experiences. Queer authors can bring out their favorite stories with a queer lens (instead of solely grasping at the straws of homoerotic subtexts); women can revisit famed tales of complex men but flatly written women with a feminist lens; Black, indigenous, and other authors of color can adapt the oppressive, colonial background of must-reads to a setting that is more about them and their people.

Related on The Swaddle:

The 1813 romance favorite Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen, had its copyright expire in 2009. Since then, it has been reimagined and adapted across VARIED generations, ethnicities, and geographies. Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavours by Sonali Dev, for example, is one such retelling. The book adapts the much–loved romance into the lives of Trisha Raje and DJ Caine, American protagonists of Indian descent, and parlays it into a bigger examination of race and privilege from a much more diverse perspective. Similarly, Ayesha at Last, by Uzma Jalaluddin, is a South Asian-Muslim-Canadian spin of Austen’s book. It grapples with the same issues as Austen’s novel — love, marriage, first impressions, socio-economic inequalities — while also considering immigration, Islamophobia, and especially feminism.

This year, The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald, is one of the most acclaimed works that has entered the public domain. But what does this mean for art? It is a chance to finally address issues like Fitzgerald’s anti-Semitic descriptions and lack of character diversity, without new artists having to pay the fees Baz Luhrmann did with his 2013 movie. For years, book enthusiasts and scholars have been reading into the homoerotic subtext of the novel, concluding some of the characters are obviously queer. And now, we’re finally getting a queer retelling of the same: The Chosen and The Beautiful, by Nghi Vo, is a reimagination of The Great Gatsby in which the protagonist is a queer, Vietnamese woman navigating the glamour of America’s roaring 20s. Fitzgerald has also been criticized for his flat depiction of women. A theatrical adaptation with two women telling the story is in the works. The possibilities of public domain art are endless and exhilarating.

Satviki Sanjay is an editorial intern at The Swaddle. She's currently studying philosophy at Miranda House. When not studying, she can be found writing about gender, internet culture, sexuality, technology, and mental health. She loves talking to people, and you can always find her on Instagram @satvikii.

Related

Coaching Institutes Are Helping Students Cheat on Their GRE, Investigation Finds