Depression — described by the WHO as a “leading cause of disability worldwide” and a “major contributor to the overall global burden of disease” — isn’t just painful to deal with in the present. Turns out, depression can have tangible effects on our brains in the long term.

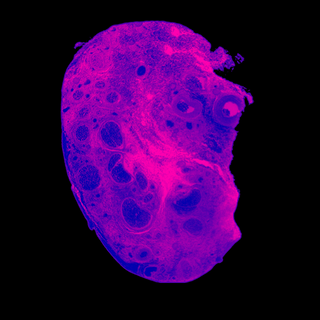

Published in Neurobiology and Treatment of Depression, a recent study found that chronic, severe depression led to “reduce[d] volume in brain regions relevant for executive and cognitive functions and emotion regulation.” In other words, it impacts parts of the brain that are responsible for regulating emotions, processing information, focusing, making decisions, planning, and remembering, among others.

We already knew that depression can impair both cognitive and executive functioning among people presently struggling with the illness — these effects on the brain often lead to them being termed lazy, irritable, and so on. The present study sheds light on its long-term impact on our bodies.

The researchers arrived at their findings by analyzing data from a cohort of 681 patients — more than 65% of whom were female, with an average age of around 35. Having gathered information about the severity and duration of the depressive disorders they went through, the researchers were able to relate both reduced gray matter in different regions of the brain.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why People Living With ADHD Are Often Misjudged As ‘Lazy’

It is pertinent to note, though, that the number of times each participant was hospitalized was used to determine the severity of the symptoms they experienced. However, not everyone struggling with depression is hospitalized — among other things, due to a lack of access and awareness.

At present, according to a study by The Lancet, the global prevalence of depression is more than 3,000 cases per 100,000 people. Since Covid19 struck, depression rates have risen worldwide; researchers have recorded a 25% increase in cases triggered by the pandemic, and everything else that accompanied it — including the grief, the mass trauma of living through a global health crisis, and the infection itself. A 27% rise in suicides among Indian students between 2016 to 2021 — with more than 13,000 students dying by suicide in 2020 alone — speaks to the prevalence of depression in India, too.

As such, the findings of the present study have put forth a jarring prospect that a significant portion of the global population could, eventually, encounter.

What’s worse is that the pandemic led even children to experience depression, which raises an alarming question: is it possible that depression’s effects on the brain’s volume impact children, whose brains aren’t fully developed, more than it impacts adults? Scientists aren’t sure yet.

Related on The Swaddle:

We Asked Experts Why It Is So Hard to Get Insurance Coverage for Mental Health in India

The present study doesn’t particularly explore the reversibility of the effects either. Past research suggests that cell atrophy and loss induced by depression are reversible through treatment with anti-depressants. However, it’s unclear whether anti-depressants might be able to reverse long-term changes, too.

What’s more worrisome for India, here — given that 56 million Indians were already struggling with depression when the pandemic hit — is the stigma against mental health that prevents people from accessing help, possibly worsening their tryst with the disease, in the process. According to the WHO, more than 75% of people in low-and-middle-income countries do not receive treatment for depression; the National Mental Health Survey in India, published in 2016, revealed that nearly 80% of Indians dealing with mental disorders had not sought treatment despite suffering for more than 12 months.

India faces a mental health epidemic it’s not prepared to address. Now that we know the pandemic can cause long-term changes to our brain structures, it’s high time we stopped being in denial about mental illnesses.